NOTE

*In keeping with USSOCOM Policy, Special Operations Soldiers Major and below and the operational objectives in this article have been given pseudonyms.

In September 2006, the “Desert Eagles,” 1st Battalion, 3rd Special Forces Group (3rd SFG), operating as Task Force-31, fought to drive Taliban forces out of the strategically important Panjwayi Valley, 35 kilometers southwest of the city of Kandahar, Afghanistan. Operation MEDUSA was designed to push the Taliban out of their traditional stronghold. The subsequent failure of the NATO/ISAF (International Security Assistance Force) to retain control of the strategic valley after Operation MEDUSA enabled the Taliban to return in the late fall. In January 2007, another campaign, Operation BAAZ TSUKA, was required to drive the Taliban out of the valley again. This article focuses on the action of C Company, 1/3rd SFG that ousted the Taliban from the Panjwayi during Operation MEDUSA. Learn more about Operation BAAZ TSUKA in this article.

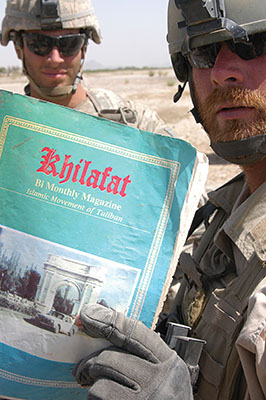

The city of Kandahar and Kandahar Province have always played a significant role in Afghanistan’s history. The province’s fertile valleys make it one of the “breadbaskets” of the country. The ancient city of Kandahar has been an important population and trade center since the time of Alexander the Great.1 The British repeatedly occupied Kandahar in a succession of Anglo-Afghan Wars lasting from 1830 to 1870.2 During the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan from 1979 to 1988, Kandahar was a center of Mujahideen resistance against the Soviet Army. There was heavy fighting in and around the city until the Soviet withdrawal.3 Kandahar is widely considered to be the birthplace of the Taliban, the radical Islamic militant group that gained control of Afghanistan in 1994.4 It was their final redoubt before U.S. and Afghan forces drove them from power in December of 2001.5 This city, the province capital, has great symbolic meaning to the leadership of the Taliban’s fiercely dedicated fighters.

Kandahar is more than just symbolically significant in the continuing fight for southern Afghanistan. It is “the key to central and northern Afghanistan. And Panjwayi is the key to Kandahar.”6 The Panjwayi District, beginning 35 kilometers southwest of the city encompasses the Arghandab River valley. The river is part of an extensive watershed that creates a broad, fertile region in the desert of southwest Afghanistan. The valleys provide natural lines of communication between Kandahar and Taliban safe havens in Pakistan. Residents of Panjwayi raise grapes, corn, and other crops making it the breadbasket of Kandahar and the surrounding country.7 The 3rd SFG soldiers were returning to a familiar place.

The “Desert Eagles,” (TF-31), were no strangers to Afghanistan. The battalion was starting its fifth rotation in the war-torn country since U. S. Special Forces (USSF) helped the Afghan Northern Alliance (in the north) and Anti-Taliban Forces (in the south) drive the Taliban from power in late 2001. Many veterans were returning for their third, fourth, and even fifth combat tours. Many had first-hand experience in the Panjwayi. Prior to leaving Afghanistan in early 2006, the 1/3 SFG company commanders were assigned operational areas for their next rotation.8

The Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force- Afghanistan (CJSOTF-A) was led by Colonel (COL) Edward M. Reeder and his 7th Special Forces Group staff when the 3rd SFG returned in August 2007. COL Christopher K. Haas, 3rd SFG commander, assumed command of the CJSOTF shortly after Operation MEDUSA commenced. The CJSOTF-A is a multi-national command with special operations forces from twelve countries including Canada, The Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates, that directed special operations in Afghanistan in support of NATO/ISAF. ISAF is the UN-mandated force under Security Council Resolutions 1386, 1413 and 1444. 1/3 SFG was returning to the same area of operations (AO) it had from June 2005 to February 2006.9

Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Donald C. Bolduc, the 1/3 SFG commander, focused on operations to reduce the Taliban strongholds and sever their connection with the local population. Following up on previous rotations, LTC Bolduc began his security assistance strategy by improving the combat capability of the Afghan government forces. Repetitive collective training was key to building up the Afghani’s confidence in themselves.10 Bolduc’s intent was to “balance security with development and ‘nest’ the capabilities of SOF [special operations forces] with those of the conventional forces (NATO/ISAF).”11 The summer of 2006 at Fort Bragg had been dedicated to preparing for the next rotation in August.

Major Jamie Hall*, C Company, and the other company commanders took maximum advantage of the opportunity. Hall’s training plan was decentralized down to the operational detachments, who concentrated on weapons firing, driver training, communications training, and medical live tissue training (for treating battlefield wounds).12 Hall held weekly updates with his team commanders to review intelligence updates received from Afghanistan to refine tactics and respond to new developments.13 He made sure that all of his 18Fs (the Special Forces Operations & Intelligence NCOs) had the time and resources they needed to conduct detailed area studies. As a result, C Company 1/3 SFG was ready to “hit the ground running.” And they had to because Operation MEDUSA kicked off just days after they arrived.

Afghan Northern Alliance forces, with the help of U.S. Army Special Forces and coalition airpower, had cleared this region of the Taliban in early 2002. However, in the years that followed, control of the Panjwayi had gradually been lost. By late summer 2006, NATO/ISAF units entering the area were regularly attacked by 100 or more fighters. The impetus for Operation MEDUSA was increasing evidence that the Taliban were massing for a major offensive against the city of Kandahar. Canadian Brigadier General David A. Fraser, the NATO/ISAF commander, developed Operation MEDUSA to disrupt the planned attack and restrict Taliban access to the “the key to Kandahar,” the Panjwayi. Operation MEDUSA was designed to open Highway 1, stop the Taliban advance on Kandahar, and clear the Panjwayi Valley of insurgents.”14 LTC Bolduc had been closely monitoring NATO/ISAF plans from Fort Bragg. Though the Desert Eagles would arrive in Afghanistan just days before the operation was scheduled to commence, he thought that MEDUSA was important to the embattled country’s future and he committed to support it.15 Bolduc knew his SF teams were prepared to operate in the valley.

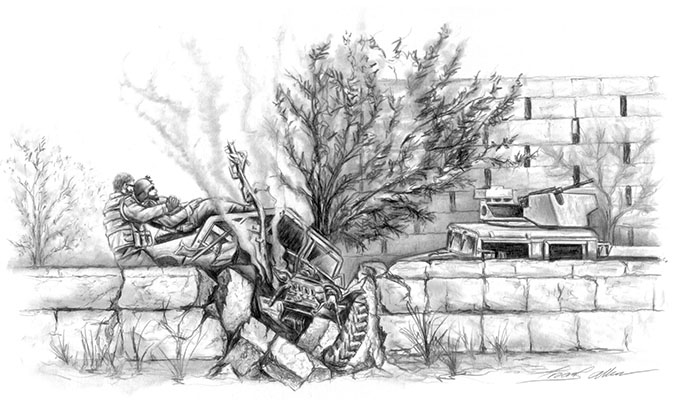

Panjwayi’s topography favored dismounted operations. The thickly clustered farms and fields provided excellent cover and concealment. The relatively large rural agrarian population was generally passive. Taliban fighters easily blended in among them. Most of the “roads” were just centuries-old foot paths through small, heavily vegetated orchards, vineyards and fields, protected by sun-dried mud walls as hard as concrete. Interspersed throughout were “grape houses” described by Sergeant First Class (SFC) Carl Freeman* of ODA 331 as “2-story huts with mud walls 2-3 feet thick. They have 6-8 inch slits in the walls for racks to hang the grapes and they are natural bunkers.”16 The terrain was especially difficult for mounted troops, more so for NATO/ISAF units that relied on armored personnel carriers (APCs) and tanks for protection.

Elements of 1/3 SFG (TF-31) began arriving in-country on 22 August 2006.17 TF-31 was to “conduct consolidation operations (defined as the combining of elements to perform a common function, in this case USSF and NATO/ISAF) to establish, maintain, or regain control of key population centers and lines of communication in the regions, provinces or districts.”18 The TF-31 “heavy lifting” was to be done by the Afghan National Army and Afghan National Police. A Company, 3rd SFG, (5 ODAs) was going to Zabel Province, and B Company (5 ODAs) to Oruzgan Province. C Company (6 ODAs) was responsible for Kandahar Province and would support Operation MEDUSA.19

MAJ Hall’s initial SOF task force for MEDUSA consisted of Operational Detachment Alphas (ODAs) 331 and 326 from B Company because four C Company ODAs, 332, 333, 334 and 335 were conducting missions in Farah, Gereshk, Herat, and Shindand respectively. Hall’s small company headquarters, Operational Detachment Bravo 330 (ODB-330), had a Special Operations Team- Alpha (SOT-A) attached to provide signal intelligence and electronic warfare support. Afghan National Army (ANA) “companies” worked directly with each ODA. The ANA “companies” were thirty-man units armed with AK-47 rifles, RPK machine guns, and RPG (Rocket Propelled Grenade) launchers.20 On 26 August 2006, ODB-330 departed Kandahar Airfield to begin its infiltration of Area of Operations (AO) FALCON*. ODA 336, which had just arrived from Fort Bragg, would join the task force on 3 September.21