DOWNLOAD

After World War II, some fourteen million refugees formed a huge stateless population in Western Europe. The Western Allies simply referred to them collectively as “displaced persons,” or “DPs.” Many released prisoners of war (POWs) trying to get home or into Western zones of Germany chose to join the population Diaspora. To provide the stability necessary for postwar economic recovery, Western Allies resettled or repatriated the bulk of them between 1945 and 1947. However, a large East European population refused to return to their Soviet-occupied countries. These people filled DP camps throughout West Germany.1 A U.S. senator who had seen how foreign units had been integrated into the German and Russian militaries envisioned the creation of similar postwar units in West Germany.2

Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., the Republican junior senator from Massachusetts, had been pushing to form a Volunteer Freedom Corps (VFC) since 1948. A VFC, filled with stateless males, would serve as a bulwark against Communism in Europe. Although some American legislators perceived its merit, postwar Western European governments regarded it as a possible economic burden and potential threat. Interest at home was not that great either.

The first and only step towards a VFC was passed by Congress on 30 June 1950, five days after North Korea invaded the South. The initial act [the Lodge-Philbin Act (U.S. Public Law 597, 81st Congress, 2nd Session), referred to as the Lodge Act] authorized the voluntary enlistment of 2,500 unmarried foreign national males in the U.S. Army.3 This act provided more than a hundred Eastern European soldiers to Army Special Forces and Psychological Warfare units between 1951 and 1955.4

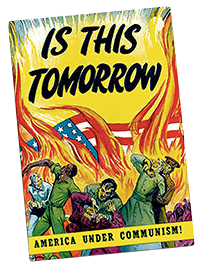

The purpose of this first installment of a two-part article is to explain the Lodge Act, to show why enlistment goals were not met, to describe the recruiting, testing, selection, enlistment and preparation for service in Army replacement centers in Germany, and the shipment of the alien enlisted soldiers to the United States for basic recruit training. Very few of the Eastern European native speakers in Special Forces (SF) in the early days were Lodge Act men. Little more than 100 of the more than 800 recruited under the Lodge Act served in SF.5 Timing was poor for several reasons: the postwar world was split by an ideological Cold War that would last more than forty years; America was in the throes of an anti-Communist Red Scare and war in Korea; and the military was slowly complying with a presidential order to racially integrate.

Like many Congressionally- mandated programs, alien enlistment got lukewarm support from the Pentagon and Army commanders in Europe. Army Regulation (AR) 601-249, Alien Enlistment, provided general guidance to enlist 2,500 Eastern European males.6 Because recruiting was a mission of the Army Adjutant General (AG), the U.S. Army Europe (USAREUR) AG was given the task. That headquarters staff element instituted an enlistment process that was based on individual applications by alien volunteers. Advertisement became the responsibility of the U.S. European Command (EUCOM) and USAREUR Public Information Offices (PIO). The foreign labor service units supporting the American and British forces in Germany and France were the easiest to target for recruits.7

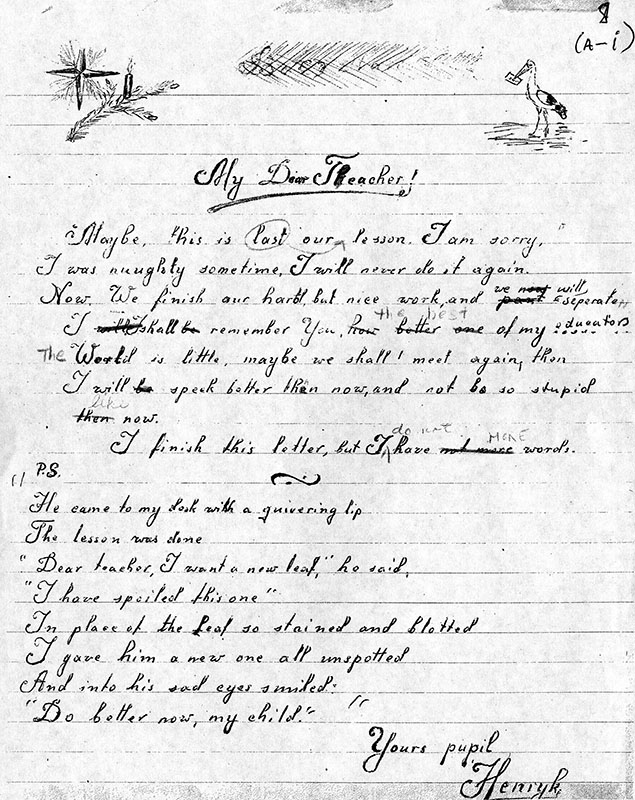

Although two-thirds of the postwar American labor force hired in Germany and Austria were natives, the U.S. Army also managed labor service (LS) elements of displaced Polish, Latvian, Czech, Lithuanian, Estonian, Albanian, and Bulgarian males, trained and organized as paramilitary guard, engineer, transportation, and public health medical units by nationality.8 In northern Germany, the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR) recruited aliens, like Henry M. Kwiatkowski from Poland, for its auxiliary service units.9 The first step was to distribute bulletin board notices to the U.S. Army personnel in charge of the LS units in Germany and France.