DOWNLOAD

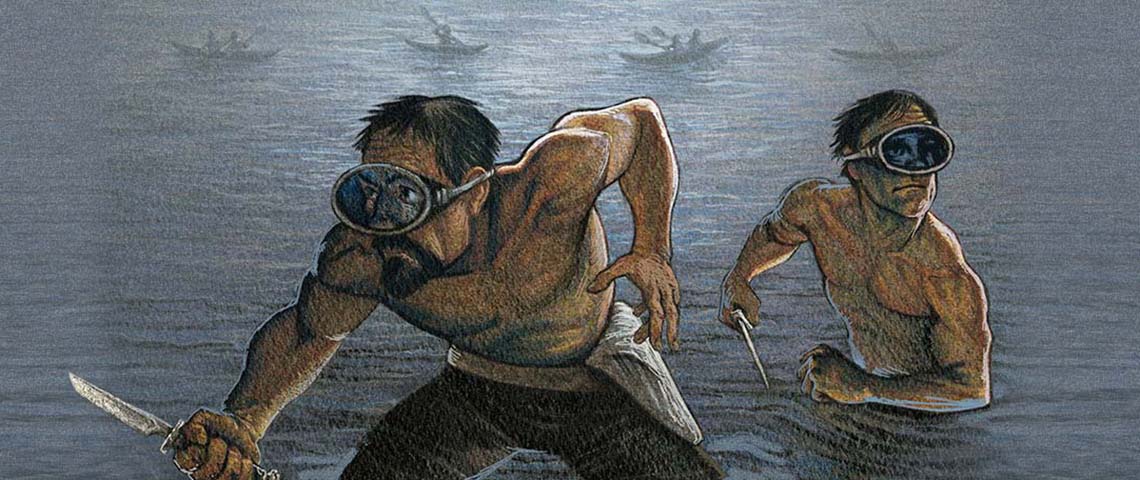

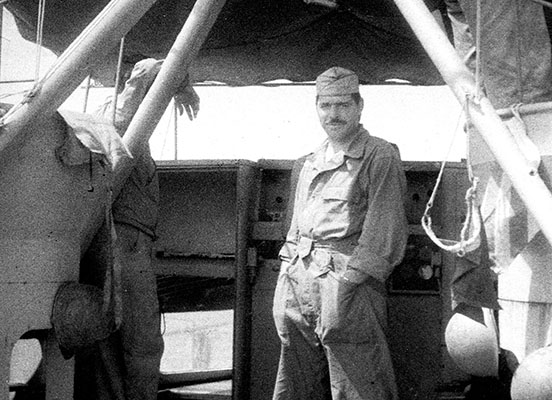

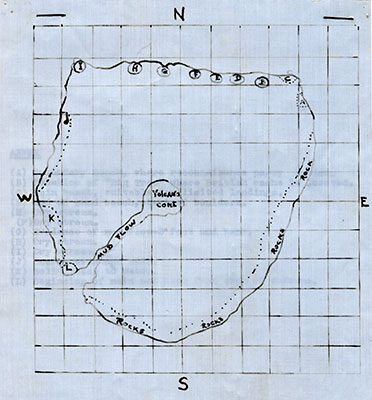

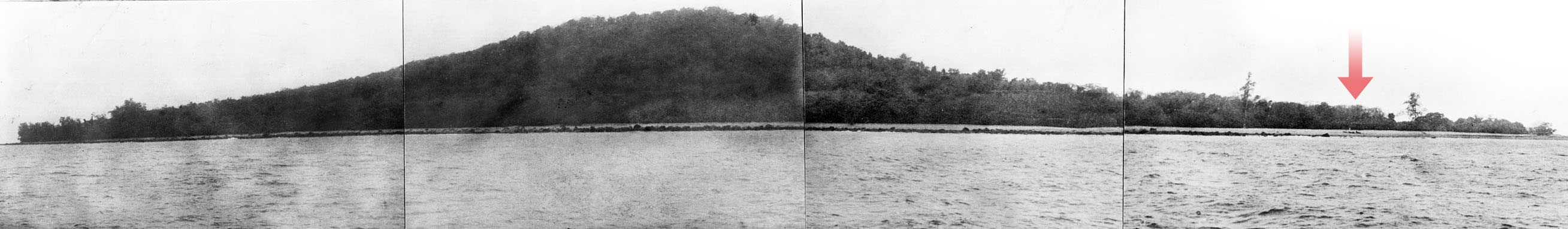

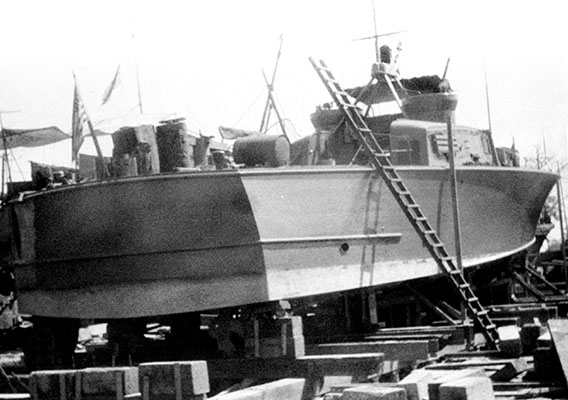

In 1025 hours on 20 February 1945, two high- powered Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Air-Sea Rescue boats eased out of Kyaukpyu harbor on the Arakan Coast of Burma to begin Operation BOSTON. Overloaded with men, equipment, and gasoline to the point of nearly sinking they headed south to go deep into Japanese-controlled waters. The boats carried a multi-service complement from two branches of the OSS. They had been tasked to reconnoiter Foul Island. Eight hours later, the forty-nine man force arrived at their destination at sunset. After circumnavigating the small island for a quick reconnaissance, the boats anchored. Twenty minutes later, four kayaks manned by eight OSS Maritime Unit (MU) swimmers cast off from P-564, commanded by U.S. Army First Lieutenant (1LT) Walter L. Mess. After silently paddling close to shore, Lieutenant Junior Grade (Lt (jg)) John P. Booth and Chief Boatswain’s Mate (CBM) James R. Eubank of the U.S. Coast Guard slipped out of their kayaks into the water. They swam to the beach. Seeing no enemy, they signaled their two kayaks to come ashore. The “safe landing” signal, a flashing red light, was sent to P-564. Then, they split into two reconnaissance parties that moved in opposite directions along the beach, a kayak trailing each from the water. They were to determine if there were any hidden enemy positions along the beach before the OSS Operational Group (OG) landed.1 It was a unique mission in an unheralded theater.

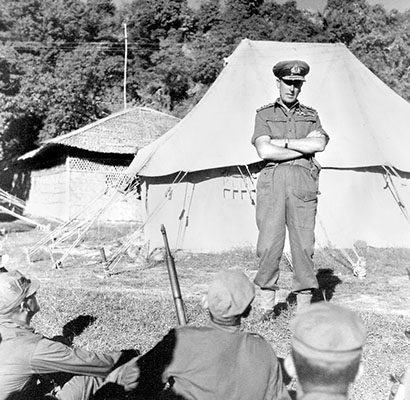

The South East Asia Command (SEAC) was perhaps the least understood theater in WWII. British Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten had operational responsibility for an area that encompassed today’s India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Southern Burma, Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and parts of Vietnam. The only American combat troops in SEAC were two small contingents of the OSS; Detachment 404 and the Detachment 101 Arakan Field Unit (AFU). Because of their small size these OSS units had to be innovative. This article explains a reconnaissance mission conducted by the AFU OG and MU in February 1945. It is relevant today because it shows how integrated operational elements from separate military services could accomplish a Coalition objective, much like ARSOF does today. But first, who these operators were is important.

The OSS OG was originally part of the OSS Special Operations (SO) Branch. They became an exclusively military branch in the paramilitary OSS on 4 May 1943. The OGs only recruited Army personnel. Their mission was to infiltrate enemy occupied territory and assist guerrilla movements.2 In general, an OG operative was a bilingual parachutist, in top physical condition, cross-trained in weapons, explosives, and communications, and always operated in uniform. Separate ethnic OGs had already served in France, Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece. The Burma OG was different because its members did not speak any of the numerous languages in the region.3 Like the OGs, the MU branch also had its origins in SO.

Originating in April 1942 as SO’s amphibious training component, MU became a separate branch on 9 June 1943 when it was apparent that the OSS needed a larger amphibious capability.4 Composed of personnel detailed from the U.S. Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Navy, and Army, it was chartered to infiltrate agents or supplies by sea, conduct maritime sabotage, and to develop special equipment.5 The pioneer of underwater warfare capabilities in the MU was Dr. Christian J. Lambertsen.

During WWII, the U.S. and Great Britain divided the globe into operational “spheres of influence” that determined which Ally commanded a particular theater; Burma, India, and that region’s ocean areas were British, while China was relegated to the Americans. The British wanted control of the entire China-Burma-India (CBI) area, as well as the American-led fighting elements in the Northern Combat Area Command (NCAC) assigned to open a supply corridor to China from north Burma. However, NCAC commander, Lieutenant General (LTG) Joseph W. Stilwell, the overall American commander of the CBI, and the commanding general of the Chinese Army in India, as well as Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s nominal Chief of Staff, would have none of it. Neither he nor OSS chief, Major General (MG) William J. Donovan, wanted Detachment 101—the paramilitary force given operational responsibility for all of Burma—under British control.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill tried to solve this conundrum by creating the SEAC in June 1943. However, this only complicated the situation in an area already divided into one operational and three geographic theaters.6 But, SEAC proved beneficial to the OSS. In return for British acquiescence to Detachment 101 retaining control over its clandestine operations, OSS/SEAC was created. Based at Kandy, Ceylon, its operational unit—Detachment 404—was under British supervision. The OSS post-war history explained that “had inter-Allied relationships been harmonious in the China-Burma-India Theater, it is probable that Detachment 404 would never have been created.”7 Because it was the smallest OSS paramilitary unit in the Far East with the largest operational environment, unique assets were required; the MU and the OGs. They were employed together along with other OSS elements in late 1944 along the Arakan Coast of Burma. The MU and OG worked so well together that years later, Dr. Lambertsen described it as “absolute.”8

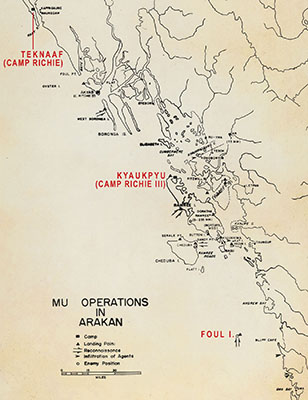

The Detachment 404 Arakan Field Unit (DET 404 AFU) began reconnaissance operations from Cox’s Bazar in India (now Bangladesh) to assist the Indian XV Corps in its drive south to secure the Burmese capital, Rangoon.9 The AFU also gathered full-spectrum tactical and strategic intelligence while conducting a propaganda campaign to destabilize the Japanese. But, the DET 404 AFU still had to react to Allied political changes. In October 1944, the American CBI Theater was dissolved. The new command structure, the India-Burma Theater (IBT) and the China Theater, caused the OSS to mirror the change.10 OSS/SEAC was replaced by OSS/IBT in mid-February 1945.11 The OSS administratively moved the AFU under Detachment 101 (DET 101 AFU).12 The reassignment did not change the AFU mission nor reduce its operational area.