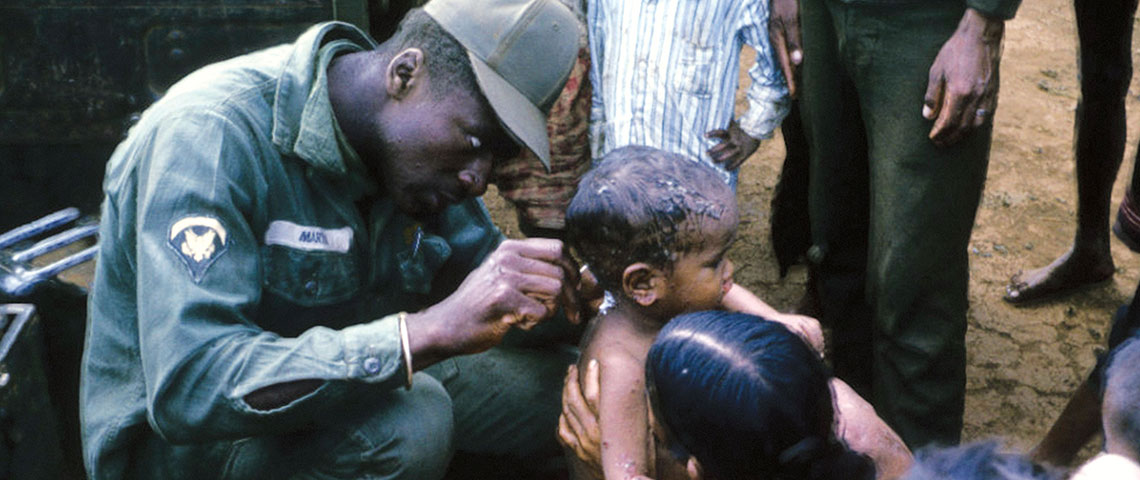

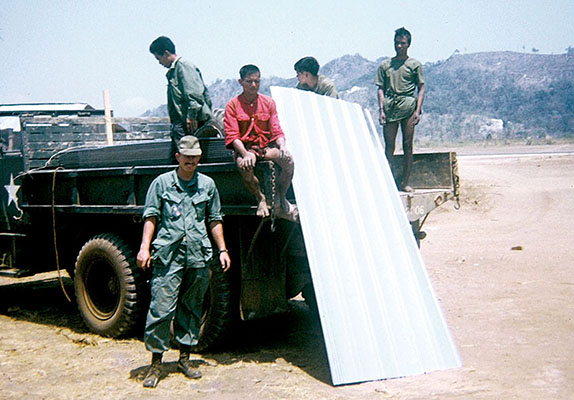

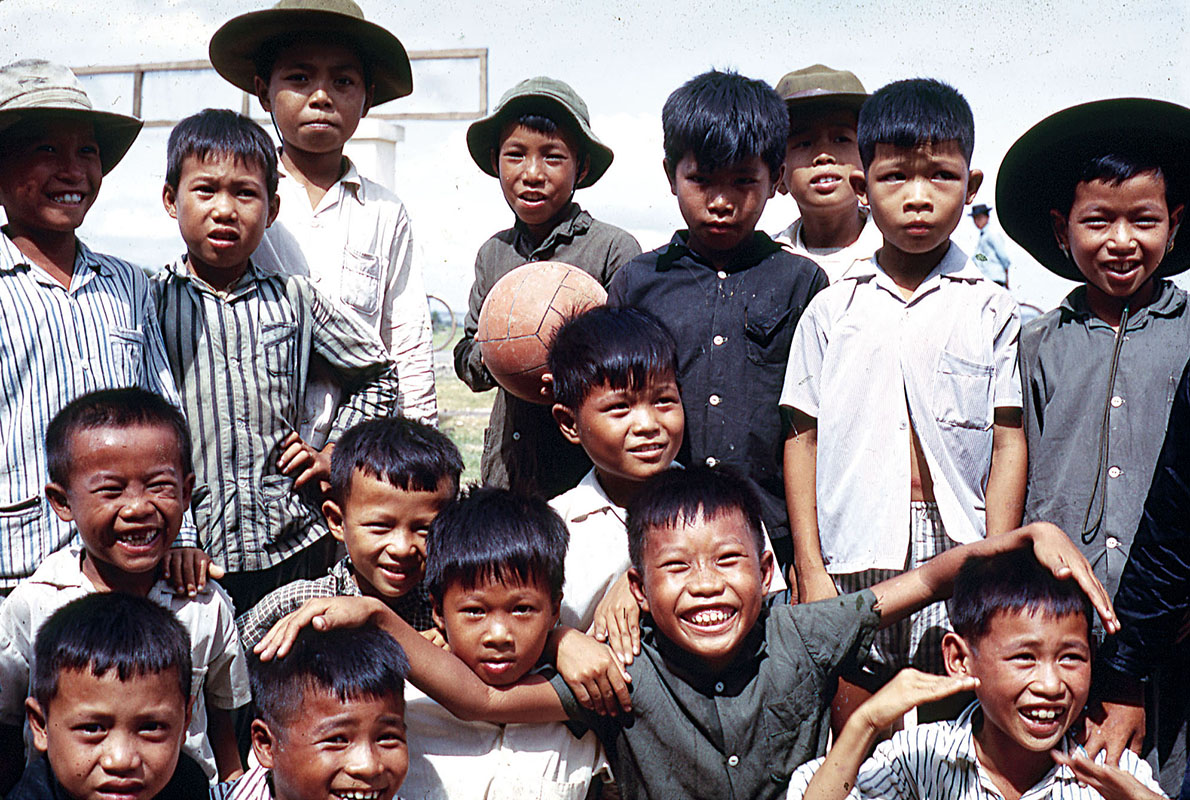

“A Peace Corps with rifles. That is one of the nicer names for the hog raisers, school marms, latrine builders, well diggers, medicinemen, and soldiers who constitute the 41st Civil Affairs Company.”1

DOWNLOAD

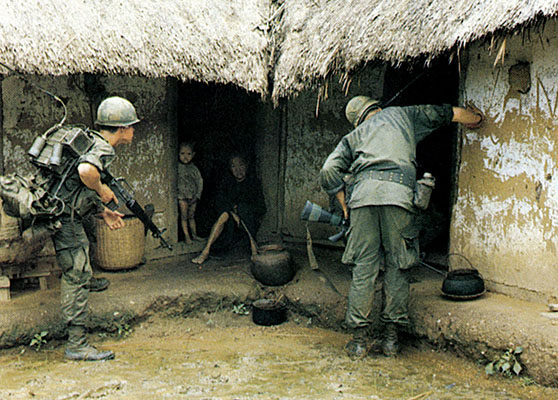

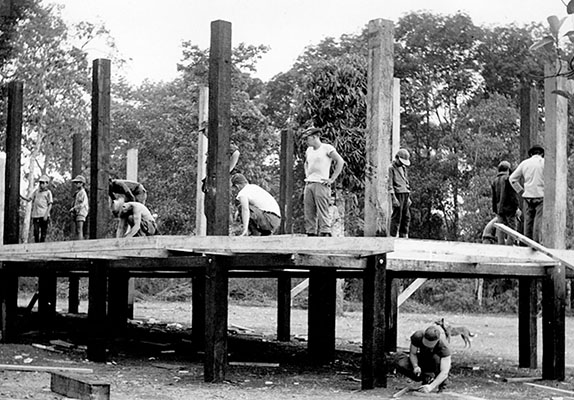

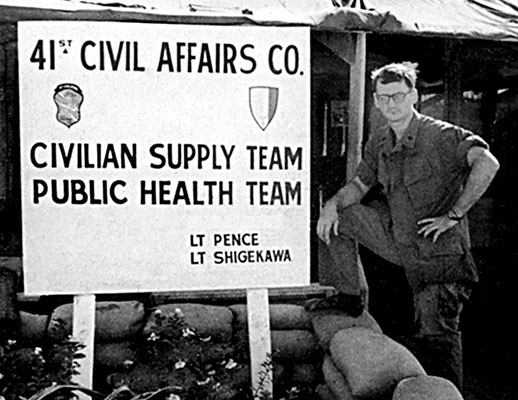

The 41st was one of only three Civil Affairs (CA) companies to serve in the Republic of Vietnam (RVN) [the others were the 2nd and 29th], and did so from 1965 to 1970. Its mission was to bolster faith in the RVN government by helping to “win the hearts and minds” of the rural population by assisting with construction, agricultural, medical, economic, and educational programs to improve standards of living. It is beyond the scope of a single article to present all 41st CA Company activities because each of the far-flung Teams has its own story. This two-part article will introduce the 41st to today’s ARSOF soldiers by providing the company’s mission, force structure, general history, and having some of the CA soldiers explain their work. Part I spans the Company’s arrival in Vietnam in 1965 through 1967. Part II will describe operations from the 1968 Tet Offensive until the 41st deactivation in Vietnam in 1970. The important message is that the 41st Civil Affairs Company persevered in the face of innumerable obstacles and made a difference. As ARSOF is challenged today to win non-violent victories worldwide, it is important to remember what the 41st CA Company accomplished forty years ago in an equally challenging environment.

The war in Vietnam was escalating in the early 1960s. Created to fight a conventional war and mirrored after the conventional U.S. Army, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) was plagued by corruption and weak leadership. These factors encouraged the loosely-organized South Vietnamese Communist movement, the Viet Cong (VC), to grow and expand their control in the countryside through guerrilla warfare. By 1964, VC units, supported by the North Vietnamese Army (NVA), began to attack ARVN forces. The situation became so acute that the United States began to send large conventional military units to South Vietnam in 1965 to prevent Saigon from falling. That year, the U.S. Army fought its first large-scale battles in Vietnam. But in reality, there were two wars ongoing in Vietnam: a conventional war against NVA-trained VC Main Force battalions; and a counter-insurgency war against the VC guerrilla units country-wide.2 U.S. Army Special Forces had been engaged in South Vietnam since 1960, but early Civil Affairs efforts were only cursory.

Individual officer advisors and Mobile Training Teams (MTTs) constituted the initial U.S. Army CA commitment to South Vietnam. Some of these MTTs recommended a larger CA role.3 Though two-man CA Teams were an integral part of Special Forces “B” detachments in country, they were only making a token effort at civil assistance.4 It was 1965 before the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), the unified command for all U.S. forces in Vietnam, requested a permanent American CA presence. The civilian U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) was in charge of the major civilian assistance programs. This changed with the MACV request.

On 27 August 1965, the 41st CA Company, 95th Civil Affairs Group at Fort Gordon, Georgia, was alerted for deployment.5 Its only previous operational experience had come earlier that year when small elements were attached to the 42nd Civil Affairs Company in the Dominican Republic. However, the lessons learned in Santa Domingo had little application for Vietnam. To satisfy MACV guidance, the 41st reorganized into sixteen “Displaced Persons Teams,” three specialized teams covering Public Health, Labor, and Public Welfare, and a command and control headquarters. It was brought to its full Table of Organization and Equipment (TO&E) strength of 75 officers and 65 enlisted men. New arrivals were given a cursory three-day course at the U.S. Army Civil Affairs School.6 Second Lieutenant (2LT) Lawrence A. Castagneto recalled that the training they received before deployment was based on WWII Military Government models that were not very applicable to Vietnam. Unit members were told that they “were going to be part of MACV … but the intent was to support the infantry and work with the civilians,” recalled 2LT Castagneto.7