DOWNLOAD

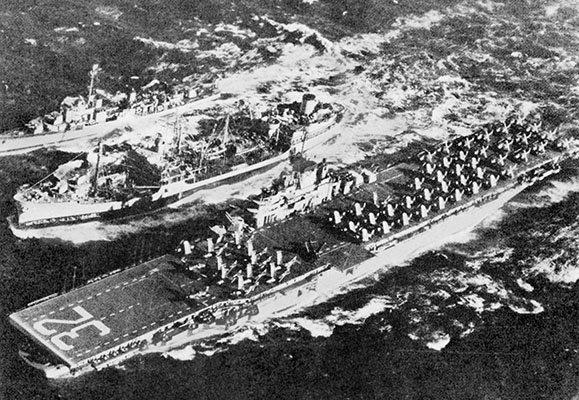

When war came to the Korean peninsula, only the North was prepared to wage the struggle to unify the two Koreas. Although designed from the start to be a defensive force, the South Korean Army was ill-prepared for the task. Likewise, the U.S.—which had not even acknowledged the possibility of war—was caught flatfooted.

NORTH KOREA

Unlike either the United States or South Korea, North Korea had been preparing for war since 1946. Details on its armed forces at the time are spotty. The ground forces were separated into two “branches.” The first was a heavily indoctrinated 50,000-man internal security force that included an 18,600-man Border Constabulary organized into five brigades, most of which were as well-equipped as the regular infantry forces.1 The second branch was the North Korean People’s Army (NKPA).

Although estimates vary widely (as high as 223,038), most sources in June 1950 report that the NKPA fielded nearly 117,000 troops (in addition to the Border Constabulary) in the invasion force.2 These soldiers were organized into two Corps consisting of seven assault infantry divisions, an armored brigade, three reserve divisions, a separate infantry regiment, and a motorcycle reconnaissance regiment.3 At full strength the NKPA infantry divisions—organized on the Soviet model—stood at eleven thousand men with an integral artillery regiment and SU-76 self-propelled gun, medical, signal, anti-tank, engineer, and training battalions.

Despite the discrepancies in troop levels and unit organization, however, sources do not disagree that the North Korean troops were better trained than their counterparts. Many North Korean soldiers were combat veterans, having served in WWII and after in the Japanese, Soviet, and Chinese Armies. The number of soldiers with prior service in the Chinese Communist Forces’ war against the Nationalist Chinese and Japanese in WWII was estimated at a third of all North Korean forces.4 In addition, Soviet advisors served at the division level.5 The North Koreans were also better armed and possessed heavier weapons than the Allies.

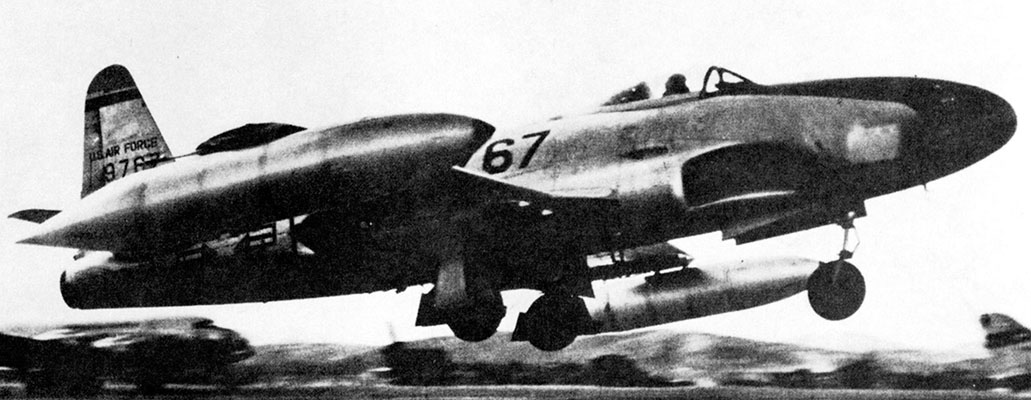

Chief among the heavy weapons for which the Allies had few counters was the Soviet-produced T-34/85 tank. Widely considered one of the best tanks of WWII, the T-34/85’s thick armor and 85 mm gun meant that the Allies did not have an equal on the peninsula to counter the approximately 150 North Korean ones.6 The NKPA also had heavier artillery with longer ranges. Additionally, their Air Force possessed at least forty Yak-9 and Yak-3 fighters and seventy Il-10 light bombers (all propeller-driven Soviet-produced WWII aircraft) for which the ROK had no counters.7 The capability advantages of the NKPA were clearly demonstrated in the early days of the war.

SOUTH KOREA

Like the U.S. Army advisors and the Far East Command, the Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) was also surprised by the North Korean invasion. However, in contrast to the U.S. Army, it was rapidly building up, not cutting capabilities. The ROKA dated to November 1945, originating as a police constabulary. Both South Korea and the United States recognized that a constabulary was an inadequate defense force.

In 1948, efforts were made to transform the paramilitary police forces into an army modeled on current U.S structure. A large pool of former soldiers who had served with the Chinese or Japanese in WWII were available as recruits.

By June 1950, the ROKA had rapidly transformed into a ninety-eight thousand-man force organized into eight infantry divisions and a cavalry regiment.8 However, only four of the infantry divisions were at their full ten thousand-man authorization. Three of these full-strength divisions, and one understrength one, were deployed along the 38th Parallel.

The remainder performed security duties or fought North Korean sponsored guerrillas in the countryside.9 In contrast to the North Koreans, the ROKA had neither tanks nor long-range artillery. And, aside from a few training and liaison aircraft, the South Korean Air Force had nothing to oppose the fighter and bomber assets of North Korea.