DOWNLOAD

Initial efforts by Republic of Korea (ROK) military forces and General Douglas A. MacArthur, Supreme Commander, Allied Powers (SCAP) and the Commander in Chief, Far East Command (FECOM) to halt the North Korean invasion on 25 June 1950 proved unsuccessful. Poorly-led ROK ground forces with their American advisors were easily routed. MacArthur committed minimally trained and woefully under-strength elements (three regiment divisions of two battalion regiments) piecemeal to bolster ROK units, hoping to stem the advance, trading space for time. When Lieutenant General (LTG) Walton H. Walker, the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) commander, chose to form a defensive bastion around the southeastern port of Pusan, General MacArthur directed special operations behind enemy lines to reduce pressure on depleted ROK and American forces withdrawing towards that sanctuary.1

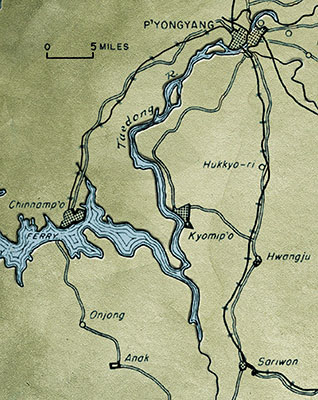

After fighting desperately to hold its lines along the Pusan Perimeter, the Eighth Army broke out immediately following General MacArthur’s daring X Corps amphibious landing at Inch’on in mid-September 1950. That offensive maneuver severed the major enemy supply lines, enveloped several North Korean divisions, and opened the way for the liberation of Seoul. ROK elements pushed north across the 38th Parallel before U.S. President Harry S. Truman approved the destruction of North Korean military forces with one caveat: as long as no Chinese or Soviet forces had entered, or threatened to enter the divided country. The limit of advance would be the borders and only ROK soldiers were to operate along them. Once the South Korean capital was secured, rapid advances to reach the Yalu River border along west and east coasts were planned. The race for North Korea was on, but the EUSA would get the “plum,” P’yongyang, the capital city. Ancillary to the advances was UN occupation and control of the enemy cities.2

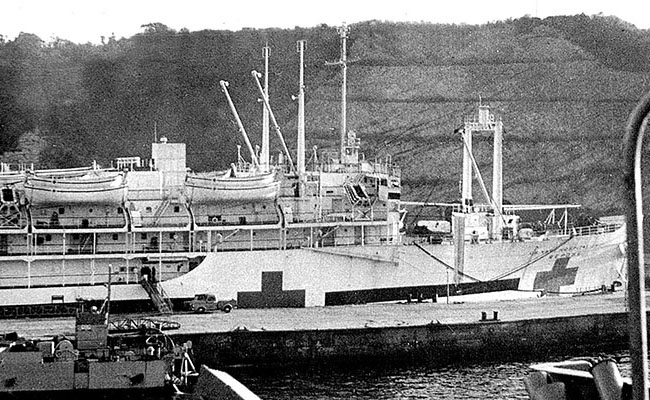

The Eighth Army staff scrambled to identify experienced U.S. Army civil military government and trained civil affairs officers to perform “civil assistance” missions. The United Nations did not like what those military skills represented, namely post-war Allied occupation governments that still existed in Europe and Japan. While the UN Civil Assistance (CA was the acronym used by the UN during the Korean War) Team for P’yongyang had specific government requirements as its primary mission, that was not the case for the CA Team sent to Chinnamp’o, the principal port for the Communist capital. They were to organize the local governments and manage the population to support U.S. Army port operations and to keep any refugees from interfering with the EUSA logistics effort that was key to continuing the drive to the Yalu River. That CA team enabled the logisticians to totally focus on resupply and evacuation of the wounded by sea. The purpose of this article is to explain this U.S. Army-unique civil assistance mission by describing the team organization and duties and what it accomplished in a very short time. These CA personnel in Chinnamp’o had to be just as flexible and capable in Korea in 1950 as are Civil Affairs today throughout the world.

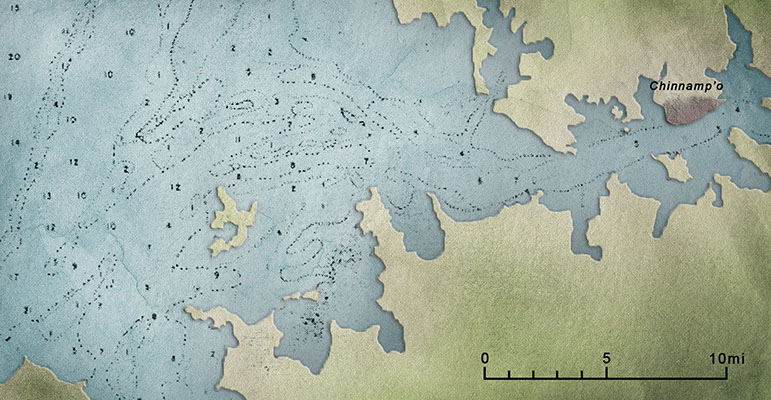

Civil military units were needed to restore law and order and rebuild vital infrastructure in occupied cities, to control refugees, and prevent epidemic outbreaks which could hinder Allied operations. General MacArthur, conducting an economy of force action, allocated his limited maritime assets to reload the X Corps for a second amphibious operation at Wonsan to launch the UN drive north in the east. That meant that Inch’on would become the port by which the EUSA, pushing north in the west would receive resupplies. That caused LTG Walker to limit his advance just beyond the Communist capital. Hence, opening the port of Chinnamp’o thirty air miles to the south on the Taedong River, was essential to continue the drive to the Yalu River. Civil Assistance was needed to allow logisticians to focus on their monumental tasks. Infantry Captain (CPT) Loren E. Davis, Headquarters & Headquarters Company (HHC) commander for 3rd Battalion, 38th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division was enroute to the Yalu River when he was unceremoniously reassigned to EUSA headquarters in Seoul.3

“There were no orders, only an Eighth Army radio message. CPT Craxton, a World War II tanker who served in Military Government in Germany afterwards, and I, after being accused by the battalion commander, LTC Brachton, of having ‘friends’ at division, were instructed to report to Eighth Army headquarters in Seoul. We collected our personal gear and ‘hitchhiked’ rides to the capital,” said LTC Loren Davis.4 Finding his own way was a portent of how he would get things done in Civil Assistance.

Davis, a 71st Infantry Division veteran wounded 4 May 1945 in Germany, was discharged after the war. Accepting a Regular Army commission in 1946 led to a three-year overseas assignment with a military government unit on Okinawa as a Chief of Police and Provost Judge (somewhat like a Justice of the Peace). With the EUSA occupying parts of North Korea in September 1950, soldiers with civil military government experience were needed. A personnel records screen for this qualification found him. When CPT Davis reported to the Military Government section of G-3, Eighth Army, Brigadier General (BG) William E. Crist, the recently designated Military Governor of North Korea, instructed him to form a Civil Assistance sub-team for Chinnamp’o. The element would be subordinate to ArtilleryColonel (COL) Charles R. Munske, the Pyongan-Namdo Province CA team leader in P’yongyang. Munske was a WWI and WWII veteran with extensive civil military government experience in the Philippines and was the Military Governor of Kyushu in post-war Japan.5 Davis’ team was hastily pulled together.

Coast Artillery Major (MAJ) Oswaldo Izquierdo from the Puerto Rican Army National Guard would be the nominal commander. But, General Crist was simply ridding himself of a problem officer.6 BG Crawford F. Sams, the director of the U.N. Public Health and Welfare Detachment, explained common refugee medical problems and assigned CPT Francis H. Coakley, a public health physician, and Canadian Red Cross epidemiologist, Reginald Bowers, to the Chinnamp’o sub-team. CPT Davis was to recruit another officer, three enlisted men, and interpreters as well as collect the equipment needed for a sustained effort.7

“The port was vital to resupplying Eighth Army. We were to appoint a mayor, police chief, and other city government positions and insure that law and order were restored. All North Korean refugees were to be controlled and prevented from clogging up roads used by the advancing UN forces. Medical evacuees from the front were to be prepared for shipment elsewhere. We were to handle any civilian problems in the city so that the logisticians could concentrate on running port activities,” remembered Loren Davis. “Stated simply it was: ‘Go to Chinnamp’o and see what you can do.”8 While Davis recruited, organized, and equipped the CA sub-team for its mission, the 1st Cavalry Division with the 24th Infantry Division on its left flank was leading the I Corps charge towards the North Korean capital city.9 Capturing the port of Chinnamp’o was initially a secondary mission.

After securing P’yongyang, the 1st Cavalry commander, MG Hobart R. Gay, had the 7th Cavalry Regiment force march the thirty-five miles southwest to Chinnamp’o to secure the port city in the dead of night, 22 October.10 As they approached, the North Korean military, after mining the channel approaches, withdrew. But, it was the damage to the lines of communications between Seoul and P’yongyang by the American Air Force that slowed the EUSA offensive to a crawl beyond the capital.

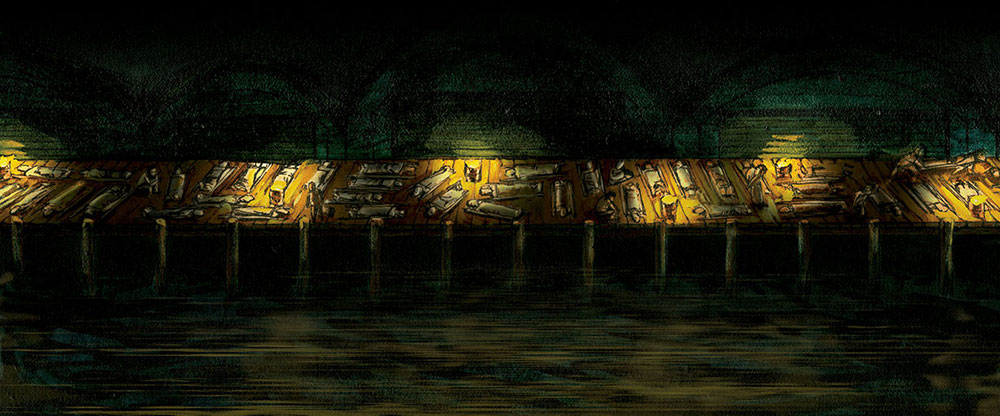

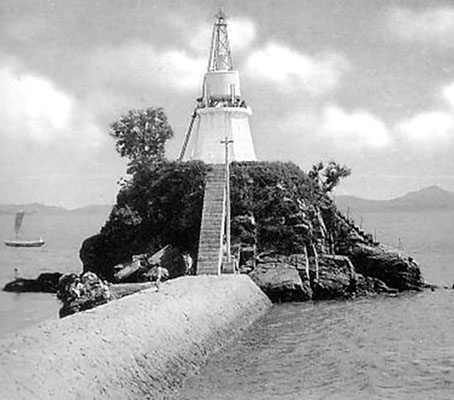

UN airpower had seriously damaged or destroyed all bridges and rail track from Seoul to the coast and north to P’yongyang as well as the harbor facilities at Inch’on. To further complicate the EUSA logistics problem, the long (seventy miles), narrow channel to Chinnamp’o was mined. In the Communist capital there were no usable rail bridges across the Taedong River that divided the city. Hence, all military supplies had to be trucked from Pusan and Inch’on to the south side of the river, loaded aboard ferries, and carried across to the north side. Then, the supplies were transferred to railcars to go further north.11

EUSA supplies were handled by the 2nd Logistical Command (BG Crump Garvin). The subordinate 3rd Logistical Command (BG George C. Stewart) provided port, depot, and transportation units in the Inch’on-Seoul and Chinnamp’o-P’yongyang areas.12 Additionally, the two logistical commands operated POW camps in Pusan, Inch’on, and P’yongyang holding 130,921 captives.13 It was no wonder that a CA sub-team was needed to work alongside the port unit at Chinnamp’o.

While EUSA pushed towards P’yongyang, CPT Loren Davis was recruiting at the various Army replacement depots in Seoul. First Lieutenant (1LT) George A. Brown, a WWII infantry veteran of the 32nd Infantry Division in the Philippines, had recently arrived from the Far East Command (FECOM) GHQ (General Headquarters) in Tokyo and was slated for assignment to the 25th Infantry Division. Davis convinced LT Brown to accept the Police Advisor position on the CA sub-team and the two started looking for enlisted men.14

After civil military government in postwar occupied Okinawa, CPT Davis wanted experienced infantrymen on this wartime effort. “Two wounded corporals returning from the hospital fit the bill. Infantry Corporal (CPL) F.R. Wade, North Carolina, who exuded a positive ‘can do, will do’ attitude had two Purple Hearts and his buddy, a somewhat slovenly CPL Shawver, a thirty-year-old farmer from Kansas, wounded three times, was headed back to the front having almost recovered from his wounds. They had earned a better assignment and were more than ready to join the team,” recalled Davis. “The two of them recruited SGT Nick to be the mess sergeant. Nick epitomized Sergeant Rizzo from the old TV series, ‘MASH’.”15

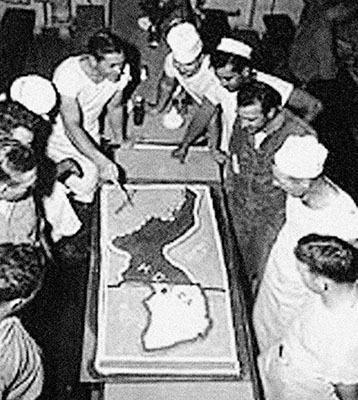

However, as it turned out the two most valuable recruits came looking for CPT Davis and LT Brown. “Kim Sam Yul, a married, out-of-work college professor, spoke academic English very slowly and precisely. As a boy he had been schooled by American missionaries. ‘Samuel Kim’ was also fluent in Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, and two Chinese dialects. He had left his family in Pusan and returned to Seoul hoping to get a job with the American military. It didn’t matter where we were going. His timing couldn’t have been better. We needed an interpreter and Sam was a godsend,” said Davis.16 The second “interpreter” from Japan became the sub-team’s cook.

“Mr. Oh’Ashi, a former Japanese Army supply sergeant and amateur gourmet cook, had adopted the Korean name of Song Ho Jung. Discovered by a general while cooking in an officers’ mess, SGT Oh’ Ashi went to Paris to serve the military attache until the war ended. The ex-prisoner of war (POW) was shipped home. He went to Korea to work in an American officers’ mess where LT Brown met him. Since we weren’t authorized a cook, I hired him as an interpreter. After all, he could say, ‘Yes, my captain,’” laughed Davis.17

It took CPT Davis more than two weeks to assemble the eight-man CA sub-team and get it equipped with weapons, winter clothing, tents, sleeping gear, and supplies. “Finding a down-filled winter ‘mummy’ sleeping bag for LT Brown was difficult. The 6’5” former University of Illinois football player was 290 pounds of muscle. The NCOs made sure that we were well-armed. Everyone got a .45 automatic and M-1 carbine with ‘crescent clips’ plus they managed to scrounge a couple M-1 Garands and a 3.5” bazooka. Since we’d be operating on our own, the infantrymen were trying to cover all the bases. Our final obstacle was transportation. We needed four Jeeps and two 3/4 ton trucks with trailers to carry us, our gear, and enough supplies for thirty days. The Corporals Wade and Shawver solved that with ‘midnight requisitioning.’ I doubt that the paint was dry when we loaded up. Taking no chances we left Seoul in the dark,” chuckled Davis.18 The CA vehicles easily wove in and out of a steady stream of six-by-six (6x6) trucks hauling supplies, ammunition, and gasoline north to the EUSA units. The trucks were Eighth Army’s lifeline.19

Unbeknownst to the CA team, the overloaded Korean rail system had broken down in October, coincident with EUSA’s rapid advance northward. That calamity put an extraordinarily heavy burden on trucks with long hauls from ports and railheads over bad roads. Spare parts were not available to keep the fleet operating on a 24-hour basis. By mid-October when P’yongyang fell, the daily number of operable trucks was so low that Far East Air Force had to airlift supplies into the city from Ashiya Air Base in Japan and Kimpo Airfield near Seoul.20 A lack of supplies caused the EUSA drive north to peter out.

The EUSA G-4 (Logistics), COL Albert K. Stebbins, estimated that a daily flow of at least four thousand tons was needed to sustain a three-corps offensive.21 Airlift from Kimpo was carrying one thousand tons daily to P’yongyang and by October’s end most planes were hauling ammunition.22 To push north of the Communist capital the main rail line from the south bank of the Imjin River had to be repaired all the way into P’yongyang and the Chinnamp’o port had to be opened.23 The time required to do this forced LTG Walker to slip his offensive start date of 15 November. It was this logistics logjam that provided the Chinnamp’o CA team the time needed to get law and order restored and city government established while the port operations were organized and the U.S. Navy cleared the entry channel of mines.