DOWNLOAD

After intense weeks of training at Fort Benning, Georgia, the Army’s four newly created Ranger Infantry companies parted ways after their December 1950 graduation. While the 1st Ranger Infantry Company (Airborne) was rushed to Korea by air, the 2nd and 4th Ranger Companies were shipped by train to San Francisco for a slower journey to war. The 3rd Ranger Company was left behind to train Ranger companies to support all active Army, Army Reserve, and Army National Guard divisions.

The 2nd and 4th Ranger Companies maintained unit integrity on board the train carrying them across the country to their port of embarkation. The only exceptions to the unit separation were the cooks, who were all consolidated to operate a single dining car. During the long train ride west, Rangers in both companies began to refer to themselves as “Buffaloes”—simply as an inside joke rising from a city-born Ranger’s mistaken identification of longhorn steers for buffalo.1

At Camp Stoneman near San Francisco, California, the Rangers exchanged some weapons and received winter clothing, the sum total of which was pile inserts for their field jackets. The 2nd Company, at least, granted no passes to visit the city while it awaited movement orders to ship aboard the USTS General H. W. Butner. The two Ranger companies joined a large group of military families on the transport ship for the long trip to Japan. Beyond Hawaii, rough North Pacific seas reduced movie and meal attendance among the Rangers, but the increasingly cold weather helped the men acclimate for Korea.2

When the USTS Butner arrived at Yokahama, Japan, on 24 December, the two slightly overstrength Ranger companies (5 officers and 105 enlisted soldiers authorized) were met by their executive officers, Lieutenants James C. Queen and John Warren, who had been flown ahead to Japan. The companies loaded their equipment and boarded a train for Camp Zama, northwest of Yokohama, where they celebrated Christmas.3

On the 29th of December 1950, the two Ranger companies boarded C-46 Commando and C-47 Skytrain transports at nearby Tachikawa Air Base to fly to K-2, an air base near Taegu, Korea. By then, Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) in Korea and the United Nations forces had withdrawn below the 38th Parallel. The 4th Rangers joined the recently arrived 1st Cavalry Division at Kimpo Air Base near Seoul. The 2nd Rangers were attached to 7th Infantry Division (ID) elements near Tanyang.4

Major General (MG) Edward M. Almond, the X Corps commander, directed that the 2nd Ranger Company “be moved up as rapidly as possible and employed.” Thus, by nightfall on 4 January 1951, the 2nd Rangers were part of the 32nd Infantry Regiment defensive line near Tanyang. After X Corps had been evacuated from Hungnam, General Almond had deployed the 7th ID near Tanyang as part of a defensive line across the peninsula to stem the Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) and North Korea Peoples Army (NKPA) counteroffensive. Just before dawn on 6 January 1951, the 2nd Rangers fought their first combat action, from defensive positions abutting a railroad tunnel near the village of Changnim-ni.5

By the end of January 1951, combat actions at Changnim-ni, Tanyang, Andong, and Majori-ri had reduced the 110-man company to 63 combat effective soldiers. The high number of frostbite cases prompted the 7th ID to finally issue pile caps and rubber galoshes for the Rangers’ boots.6 Although vastly understrength for the mission, MG David Barr, the 7th ID commander, followed General Almond’s directive that all black soldiers assigned to the division be temporarily assigned to the 2nd Ranger Company for basic tactical training.7

The task of providing basic combat training—from individual soldiering skills to company-level infantry tactics—to all 7th ID black replacements was rotated among the three 2nd Ranger Company platoons.8 Those Rangers not serving as cadre supported the offensive operations of the 17th Infantry Regiment in the vicinity of Ch’un ch’ong. On 22 February 1951, the 2nd Rangers were alerted to join the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team (ARCT) for a future parachute operation. 4th Ranger Company was also alerted. First Lieutenant (1LT) James B. Queen, the 2nd Ranger executive officer, and Corporal (CPL) William Weathersbee, the operations sergeant, were driven by Private First Class (PFC) Lester James to K-2 Air Base to establish liaison with the 187th ARCT.9

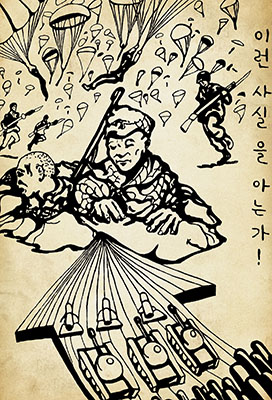

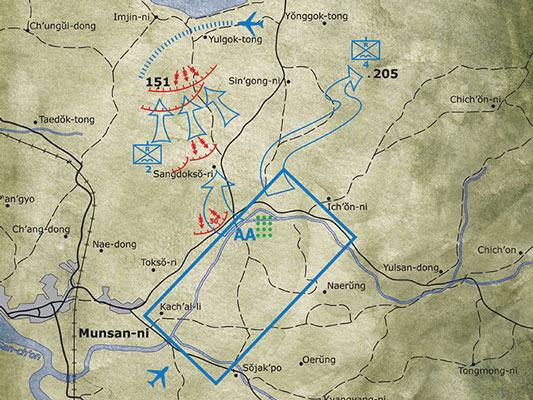

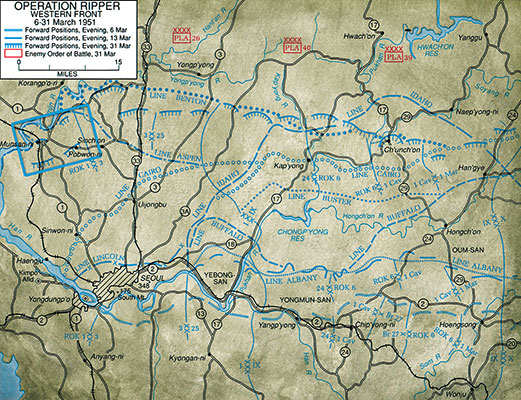

By this time, Chinese and North Korean armies were withdrawing north under pressure from counterattacking American and United Nations forces. To support a IX Corps offensive on 22 March (Operation RIPPER), EUSA had ordered an airborne assault north of Seoul to cut off retreating Communist forces. Operation HAWK called for the 187th ARCT and two Ranger companies to seize key objectives at the north end of the Ch’un ch’ong Basin on 20 March in order to block that escape corridor, and link up with the 1st Cavalry Division moving northwest. The city of Ch’un ch’ong was an important supply and communications point with a good road network in the center of the basin. When Lieutenant General (LTG) Matthew B. Ridgway encountered lead elements of the 1st Cavalry in Ch’un ch’ong during an aerial reconnaissance on 19 March, he canceled HAWK. The objective for the airborne assault was moved further north to Munsan-ni, and the execution date changed to 23 March. The replanned assault was named Operation TOMAHAWK.10

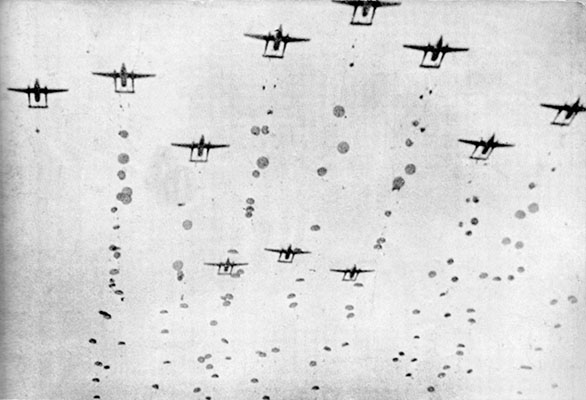

Operation TOMAHAWK was the first combat parachute jump ever made by Rangers. The airborne assault was about twenty-four miles northwest of Seoul, near Munsan-ni. The 187th ARCT mission was to smash the withdrawing NKPA 19th Rifle Division against two tank infantry task forces from the 3rd Infantry Division that would come north on the Seoul–Kaesong Highway (Task Force GROWDEN) and the Seoul–Uijong-bu Highway (Task Force HAWKINS).11 Concerned about personnel shortages, Captain (CPT) Warren E. Allen, the commander of the 2nd Rangers, had sergeants begin checking daily troop trains for airborne-qualified personnel and wounded Rangers returning from hospitals.12

Newly promoted 1LT Albert Cliette, 3rd Platoon leader, was discovered on a train headed back to the 7th ID. Wounded in the leg while “attacking some nondescript hill” in the Ch’un ch’ong operation, Cliette had been evacuated to a Mobile Army Surgical Hospital near Pusan. “When the guys told me about the Munsan-ni operation, I grabbed my .45 caliber Thompson submachine gun and field gear and jumped off that train. It was to be a combat jump—the paratrooper’s dream,” said Cliette. “1LT Bernard B. Pryor, the 1st Platoon leader, wounded in the same action as me, had fought with Merrill’s Marauders in Burma during World War II. His steel helmet saved him from being killed by a sniper’s bullet that punched clean through the lieutenant bar on the front. Fortunately, the bullet, slowed by the helmet liner, just plowed across the top of his skull, neatly parting his scalp. Because the top of his head was super-sensitive afterwards, Pryor couldn’t wear a helmet. He couldn’t jump without a helmet so he was put in charge of bringing the individual ‘A and B bags,’ supplies, mess team, and two Korean officer interpreters to the drop zone aboard a truck convoy. Unsure about the Korean attachments, they tried to reassure us by saying, ‘Do not worry about us. We watch you guys and do what you do. Everything OK.’ ”13

By 28 February 1951, the 2nd Rangers had joined the 4th Rangers at K-2 Air Base, near Taegu, for Operation TOMAHAWK. Attached to the 2nd Battalion, 187th Infantry, the Rangers were assigned to a group of squad tents next to an apple orchard. “There was no dispersion of the units, just row after row of tents. Air attack did not appear to be a concern,” said Sergeant (SGT) Joe C. Watts of the 4th Ranger Company. “The tents had straw-filled mattress ticks for sleeping.”14 “I knew it would be a combat jump when the MPs [military police] locked the K-2 airfield gate behind us,” said PFC Donald Allen, an original recruit from K Company, 3rd Battalion, 505th Infantry, 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina.

Credit: 75th Ranger Regiment

The Rangers and the 187th dedicated two weeks to preparing for the mission. The Rangers practiced small unit infantry tactics from squad to company level; zeroed their rifles, carbines, Browning Automatic Rifles (BAR), and .30 caliber M-1919A6 light machineguns; and fired the two-part 3.5-inch antitank rocket launchers and 60 mm mortars. The officers focused on learning 187th ARCT standing operating procedures (SOP). The 4.2-inch heavy chemical mortar, fougasse (a field-expedient jellied gasoline explosive in fifty-five gallon drums), and aerial resupply were also demonstrated by the 187th. Only supplies and ammunition would be airdropped during Operation TOMAHAWK. Planning was aided by the terrain sand table that CPL Weathersbee built. During the Rangers’ stay at K-2, replacements from the States arrived to fill losses.15

1LT Antonio M. Anthony, who received a battlefield commission with the 92nd ID in Italy during World War II, brought thirty black airborne Ranger replacements from Fort Benning, Georgia. The 7th Company in the Army Ranger Training Command had a black platoon specifically to provide replacements to the 2nd Rangers. When the men arrived, they were spread throughout the company. At a special 187th ARCT jump school, two 7th ID black soldiers, tactically trained by the 2nd Rangers, also became airborne qualified.