DOWNLOAD

The success of the amphibious landing at Inch’on had reversed the fortunes of the United Nations (UN) forces on the battlefield in Korea in the fall of 1950. Reestablishment of South Korea’s government in Seoul on 29 September 1950 allowed General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur, United Nations Commander in Korea and Commanding General, Far East Command (FECOM), with U. S. Presidential approval, to formulate a plan to extend UN operations into North Korea.1 MacArthur announced his intention to conduct a second amphibious landing at the North Korean naval base of Wonsan.

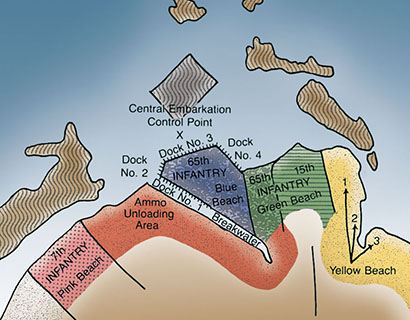

The FECOM Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group concept called for the U.S. X Corps to re-embark on naval transports at Inch´on, sail around Pusan to Wonsan Harbor and assault Korea’s east coast by 20 October 1950. The Republic of Korea (ROK) I Corps would drive north up the east coast in support of X Corps. After establishing a beachhead, X Corps would occupy northeast Korea and attack west across the mountains toward P’yongyang while the Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) attacking north from Seoul headed to the Communist capital. Dismissing concerns about splitting his forces (Eighth Army and X Corps) by terrain and distance, MacArthur believed this assault, coordinated from Japan, was in no danger of NKPA counterattacks or intervention by Chinese forces.2

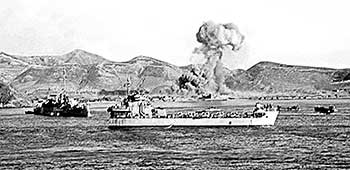

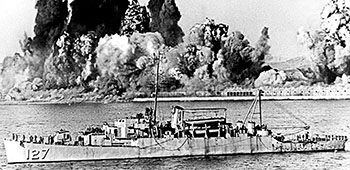

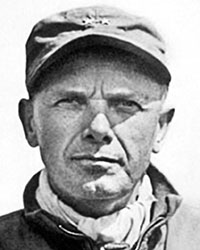

With well-constructed minefields blocking the harbors of Wonsan and Hungnam in North Korea, Major General (MG) Edward M. “Ned” Almond was quite frustrated. His two-division amphibious invasion force was stymied, with half on land at Pusan and the other half at sea. The 1st Marine Division was “yo-yoing” north and south in the Sea of Japan off the east coast of Korea. In the meantime, the ROK I Corps had attacked northward along that same coast and had captured Wonsan. By 20 October 1950, they were advancing rapidly on Hamhung, the industrial center of North Korea, and the port of Hungnam.3 I Corps established six provincial governments north of the 38th Parallel, but guerrilla operations that followed in the wake of the attacking ROK forces caused them to collapse by the end of October.4

Despite having no American ground forces ashore to command in North Korea, MG Almond decided to establish a X Corps headquarters presence on land. A small, advanced command post (CP) was shuttled into Yonp’o airfield near Wonsan aboard twelve C-119 Flying Boxcars. Navy helicopters carried the American corps commander ashore daily. Each afternoon Almond returned to spend the night on the amphibious flagship USS Mount McKinley (AGC-7) with half of his headquarters staff.5

This article explains the evacuation operations conducted by X Corps from the North Korean east coast ports of Hungnam, Wonsan and Sonjin from 9-24 December 1950. General MacArthur had directed Lieutenant General (LTG) Walton H. Walker, the EUSA commander, to form a UN civil assistance command. Therefore, the United Nations Public Health and Welfare Detachment became an integral part of EUSA. However, since General MacArthur elected not to subordinate X Corps under Eighth Army, the responsibility for civil affairs in X Corps rested with MG Almond.

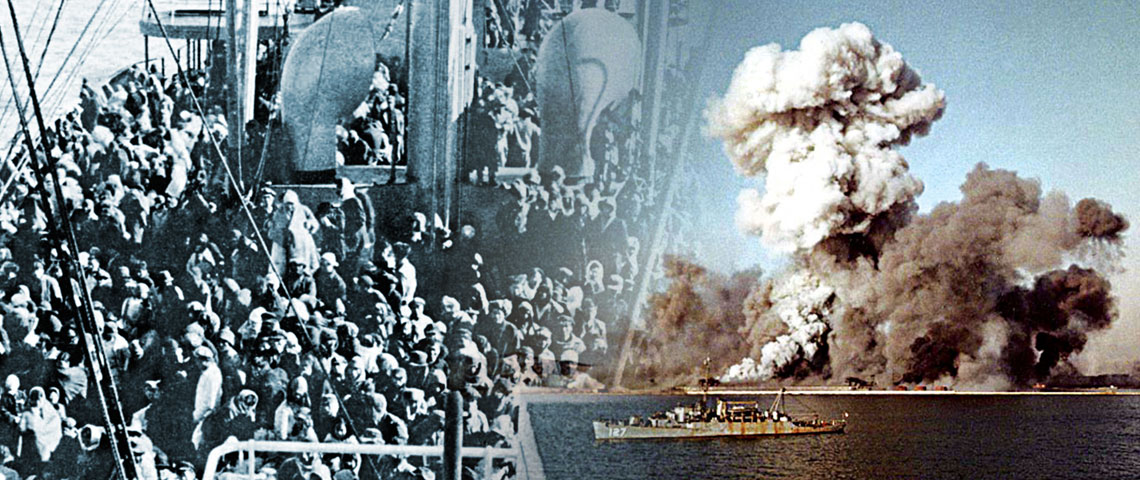

As a result, the X Corps decision to support the evacuation of almost 100,000 refugees from North Korea was accomplished using organic CA assets. They faced a more complicated refugee problem than EUSA and the UN civil assistance teams during the withdrawals south in December 1950.

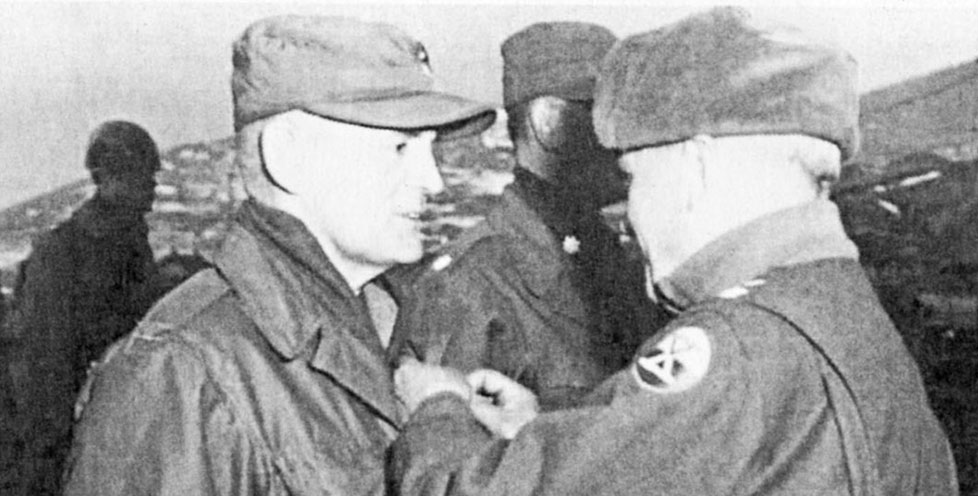

At noon on 20 October 1950, GEN MacArthur gave MG Almond responsibility for all Allied operations in northeast Korea. This authority extended to the ROK I Corps, scattered along roads north of Wonsan, the 1st Marines offshore, the 7th Infantry Division (ID) boarding ships at Pusan, and the 3rd ID in Japan being readied to reinforce the X Corps.6 Before the American troops could land, he spent a lot of time evaluating civil rehabilitation needs. Almond showcased his presence by touring the area and announcing plans to create local democratic governments. He felt that every effort within reason should be made to convince the populace that the United Nations effort to establish democratic practices in the North Korea was sincere.7

Three days later, MG Almond began speaking to city leaders and soliciting their concerns. Wonsan officials requested medical supplies, land reallocation, lumber and oil to rebuild the fishing industry, South Korean won, support for the refugees, and help finding their missing relatives. After passing out candy and cigarettes, he repeated the routine in Hamhung on 31 October, five days after the Marines came ashore. The superficiality of his ceremonies, proclamations, and promises quickly became apparent as the troops landed and immediately marched north. The limited logistics were needed to support the offensive, not to rebuild North Korean infrastructure. That would have to wait for the occupation.8

Shelby L. Stanton, author of Ten Corps in Korea 1950, labeled these city conferences as “cosmetic forgeries” and criticized the whirlwind effort by X Corps Civil Affairs (CA) teams to organize four city and twenty-four province government councils by December 1950.9 General Almond later recalled in 1952 that provincial governments had been established in 14 of 15 counties.10 Stanton claimed that they did little to restore public order. The lightly armed civilian police proved no match for Communist guerrilla bands already reinforced by North Korean military stragglers.11

There were only two small CA teams assigned to the Corps G-1 (Personnel) section. One was headed by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) James A. Moore, the Corps CA Officer responsible for Hamhung, and the other by LTC Lewis J. Raemon, the Occupation Court Officer responsible for public safety in the Hamhung-Hungnam area and CA in Hungnam. The 3rd and 7th IDs each had CA teams and the 1st Marine Division had an attached Army CA team, but these elements were focused on tactical problems. They assisted the Provost Marshal and military police (MPs) with refugee and disease control and prevented infiltration by saboteurs and guerrillas.12 Once the Corps headquarters was ensconced in Hamhung, the offensive north absorbed MG Almond.

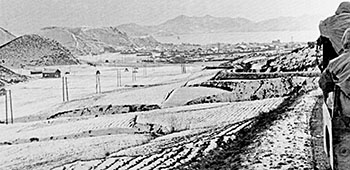

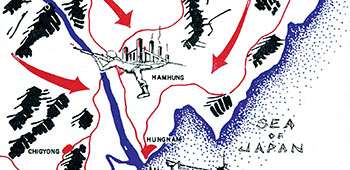

The isolation of X Corps was compounded by a daily growing separation of units as MG Almond spurred them forward to attack along three axes that “diverged like the splayed fingers of a hand.”13 Because the enemy appeared beaten, units were “deployed more in the manner of a quail hunt than a military campaign.”14 By 26 October 1950 when the 1st Marine Division landed at Wonsan along the east coast of North Korea, that country’s capital, P’yongyang, eighty miles to the west, had been controlled by the EUSA for ten days. Two very rugged north-south mountain chains separated the two major combat elements of GEN Douglas A. MacArthur’s UN command on the Korean peninsula. As the two ROK divisions charged north in trail along the east coast, the 7th ID did likewise to the north-northwest, and the 1st Marines attacked to the northwest. By late November, the advances were so rapid that X Corps elements were spread out across three hundred miles of North Korea. High, rugged mountains disrupted communications and denied mutual support when Chinese Communist Forces (CCF) intervened in overwhelming numbers to halt UN advances that threatened the People’s Republic of China (PRC).15

Massive Chinese attacks against the Eighth Army and X Corps on 26 and 27 November 1950 radically changed the military situation in North Korea. The Communist counterstroke wrecked General MacArthur’s offensive that had been poised to end the war in just a few days.16 General Almond stated, “The new conflict was recognized as undeclared war by the CCF (Communist Chinese Forces) in great strength and in organized formations.”17

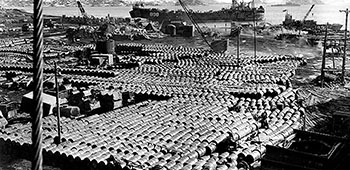

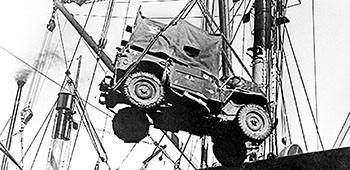

Now, the preservation of the UN combat forces on both sides of the peninsula called for orderly withdrawals that emphasized saving equipment and vehicles as well as troops. As American and ROK units pulled back, anti-Communist North Korean civilians who openly supported the several UN civil assistance teams in the west and X Corps CA teams in the east by serving as city and province officials, law enforcement, and laborers were suddenly at great risk. Flight south to safety was the preferred option.

The return of Communist officials with a strong military force prompted hundreds of thousands of anti-Communist North Korean civilians to flee south. Having already endured harsh Communist rule for five years, these refugees were “voting with their feet,” according to two seaman aboard a ship supporting the request for help.18 This flood of humanity was a major problem for X Corps.

From the start, X Corps realized the magnitude of the problem and factored air and sea evacuation of anti-Communist civilians in its planning for withdrawal from Wonsan, Hamhung, and Hungnam. But, since General MacArthur decided to withdraw on 11 December 1950, scarcely two weeks were available for the final planning and evacuation of 100,000 troops and their equipment. X Corps Operations Order No. 10, the scheme of withdrawal, however, was in the hands of troop commanders that day.19 It was empathetic staff officers, in particular USMC COL Edward H. Forney, the X Corps Shore Control Officer at Hungnam, Dr. Bong Hak Hyun, the civilian CA advisor to MG Almond, and Major (MAJ) James Short, X Corps History Section, who had garnered the general’s support to rescue the North Korean refugees after UN combat forces were evacuated.20