DOWNLOAD

A small civilian-led G-2 Psywar Section, responsible for Far East Command (FECOM) planning from the Philippines to China, had been “fighting tactical fires” since North Korea invaded the South on 25 June 1950. For over a year they had scrambled from one requirement to another. The tasks increased markedly when the FECOM headquarters was dual-hatted as the United Nations Command (UNC). In the midst of the Asian war the U.S. Army was hustling to rebuild tactical and strategic Psywar capabilities.1

Constant pressure from FECOM in the late spring of 1951 prompted Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, the Army Chief of Psychological Warfare (Psywar), to accelerate the shipment of the 1st RB&L to Tokyo. Because the unit was not fully manned and had acute print and radio broadcast equipment shortages, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Homer E. Shields, a WWII Psywar veteran and the commander of the 1st Radio Broadcasting and Leaflet Group (1st RB&L), divided his element into three echelons. A small advance echelon (ADVON) departed by air for Tokyo in early June. The main body followed by sea in July. A rear echelon, after being trained on newly acquired equipment, crated it up, and accompanied the cargo aboard ship in September 1951.2

The purpose of this article is to explain the priority missions the 1st RB&L ADVON had when they arrived in Japan. The Psywar group needed a “home” for its 3rd Reproduction [Repro] Company.3 In accordance with 1950s Psywar doctrine, the Repro Company of an RB&L was to co-locate with theater print facilities.4 But, J. Woodall Greene, General Douglas A. MacArthur’s WWII Chief of Psywar, recalled to active service from retirement, had a more pressing problem. UNC needed an official voice at the Armistice negotiations site. Why a Psywar officer was to be committed to that critical mission is the crux of this presentation.

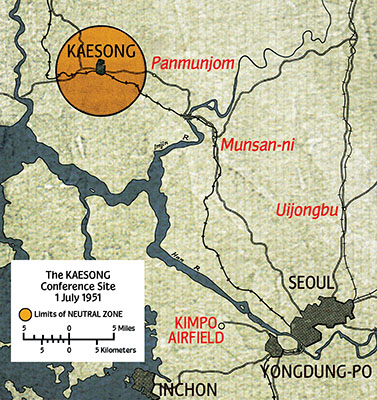

Talks to set the conditions had begun at Kaesong in the Communist-controlled area. The United Nations Command (UNC) did not have an official news presence on site. North Korea and China brought two seasoned, highly skilled, sympathetic British and Australian journalists with Party news personnel to help them with publicity. These two Western “fellow travelers” were in the official party. Conditional to starting Armistice talks the Communists had stipulated that “free press” representatives be barred from initial meetings where points of discussion and an agenda would be set. Thus, the Communists took the Psywar “high ground” since the leftist English-speaking correspondents served as spokesmen for international media at the beginning. The Allies had no one.

The U.S. State and Defense Departments, UNC and FECOM were caught “flat-footed.” American agencies soon learned that to counter Communist propaganda effectively they had to evaluate the consequences of all actions, anticipate reactions, and have well-grounded responses to keep “a step ahead” in the Cold War of competing ideologies. The Communists proved to be tough opponents who treated Western diplomatic protocols with disdain. Totally unaware of the problem when they arrived, Korea seemed a long way from Tokyo to the 1st RB&L ADVON.

Second Lieutenant (2LT) William F. Brown II related: “Wearing our combat gear with summer khaki uniforms and carrying duffle bags, we boarded a chartered Douglas DC-4 airplane in California for Tokyo. As we clambered off the aircraft at an airport near the Japanese capital, a convertible with its top down drove up. Its American driver in civilian clothes had a beautiful woman with him. His only greeting was: ‘So, you really did make it. Report to the Empire House,’ and off he drove. Our officer-in-charge [OIC] commandeered an American military bus with a Japanese driver to take us into the city. It was Saturday and few people were working. When we got to the Empire House, nobody knew we were coming. My first job Monday morning was to write a press release for a Colonel Dahlquist who was changing jobs. I don’t know whether it was good or bad because a few days later I was sent to Korea.”5

Colonel (COL) Greene, the former civilian head of G-2 Psywar, selected LT Bill Brown, a Princeton psychology graduate (Class of 1950) who had been a Look magazine writer for a short time, to cover the Armistice negotiations.6 “Why I was selected was never explained. I was told to pack my duffle bag and get to Korea. I caught military air ‘hops’ into Pusan and Seoul and ‘hitched’ a jeep ride to Kaesong. The [Armistice] talks had begun three days before I got to the UN military ‘base camp,’” said Brown.7 He was unaware that the Western correspondents had been blocked from covering the initial proceedings.

On opening day the Western news media representatives had been denied access to the site by the North Koreans. They watched as the Party press representatives and two sympathetic Western journalists trouped into the negotiation site. Therefore, only one perspective was being presented to the world. By the time LT Brown arrived, the UNC had lodged formal objections to the overlooked caveat and were scrambling to accommodate the Western journalists at a tent city near Munsan-ni. Despite improved billeting, ready access to radio teletype communications, transportation, and on-site military censors, the absence of hard information as “staffers” haggled over Armistice agenda topics upset the reporters.

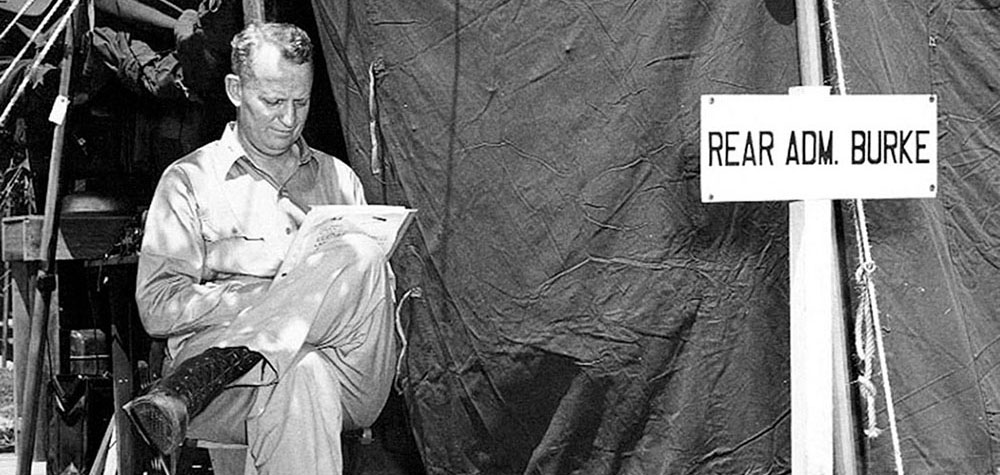

Fact-starved journalists, pressured by editors back home, quickly turned to Communist disinformation being broadcast in English from P’yongyang and Peking and to the two “fellow traveler” newsmen who accompanied the North Korean and Chinese delegations. These leftist Westerners “held court,” sharing lopsided information with the international press corps facing print deadlines at home. BG Frank A. Allen, the FECOM Public Information Officer [PIO], and BG William P. Nuckols, the Far East Air Forces (FEAF) PIO, sent to plug the gap, struggled to counter the Communist Psywar campaign.8 Having walked into this confusion, 2LT Bill Brown described the UN camp and the daily routine in a Proper Gander article.

In front of an infantry regimental headquarters was the Allied ‘peace camp’—a tent city of thirty or forty large tents and a dozen small VIP ones in the middle of an apple orchard. “It had its own movie theater with a sandbagged generator. The small projector was beset by a million nocturnal mosquitos. There was a barber shop and 48-hour laundry service,” explained Brown. “Every morning and evening the [Allied] delegates met in a tent marked ‘Conference’ to discuss Communist claims and ‘quarterback’ the next day’s activities.”9

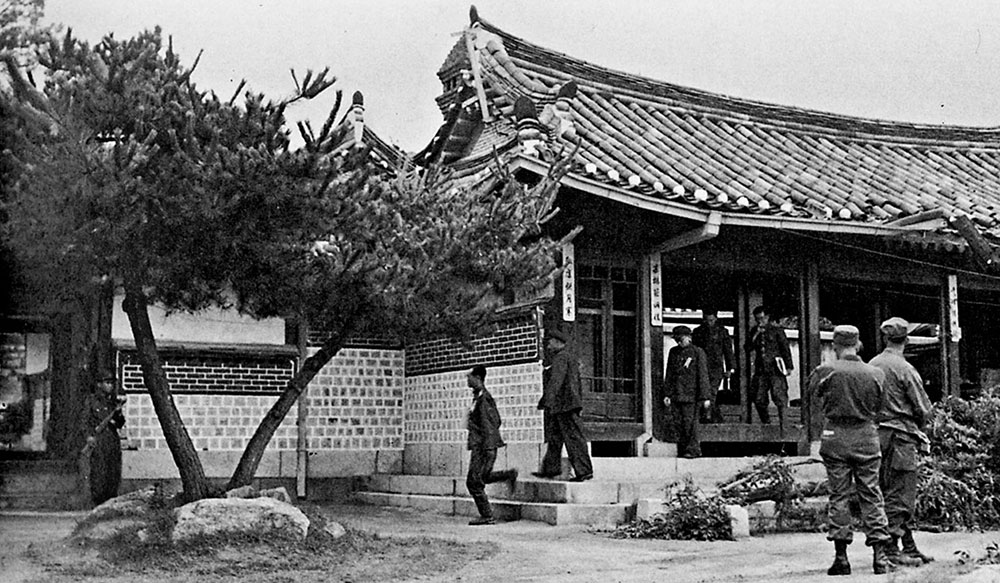

“Lieutenant Bill [William J.] Brennan [Brown’s replacement] and I, wearing .45 pistols, rode out to the Kaesong negotiations house in a jeep flying white flags. We drove down a road into the demilitarized zone [DMZ] cordoned by North Korean soldiers with burp guns,” said LT Brown. “As we sped through the ‘gauntlet’ of stone-faced Communist troops Bill joked that the U.S. Army would rush in with tanks to get our bodies if we were attacked.”10

The initial conference site was a well-known Chinese restaurant in Korea. “In its present state it wouldn’t rate a Class B permit in the States,” Brown wrote. “Painted walls and ceiling are peeling. The garden is overgrown. The vines choke out the flowers that were probably carefully cultivated two summers ago. Each Allied negotiator’s statement is usually read from a prepared script and then translated into Korean and Chinese. The discussions move slowly, and the tone is usually one of moderate iciness.”11

“Outside on a big porch Communist newsmen—mostly Korean and Chinese—cluster with an Englishman named [Alan] Winnington from the London [socialist] Daily Worker and his sidekick [Wilfred] Burchette from the Parisian [leftist] Ce Soir [and L’Humanite]. Both arrived from Peking. In another place are maybe a dozen allied newsmen. Everyone is engaged in speculation; everyone waits for the big ‘break’ to come. It doesn’t. After a few posed pictures at the end of the day, the Communists pile in their Russian-made jeeps and zoom off. The whir of helicopter blades announces the departure of the UN delegates.”12 This use of air transportation countered the dominant vehicle parking position taken by the Communists.

“After a few times waiting outside the building for hours to receive the official statement and then hurrying back to [military] camp to type a broadcast for the Voice of the UN Command [VUNC] in Tokyo, I started going to the Press Camp to await the PIO release. Then, I wrote my report and sent it by radio teletype to FECOM G-2 Psywar. To add credence to Tokyo broadcasts they referred to me as a ‘voice close to General Ridgway,’” chuckled LT Brown. “The closest I ever got to him was photographing his tent in the UN base camp at Munsan-ni. But, I did meet the FECOM PIO [BG Frank A. Allen], who got me assigned as 1st RB&L LNO [liaison officer] after covering the negotiations.”13

2LT Bill Brennan replaced Brown in mid-August. Shortly after the Communists broke off discussions on 23 August 1951 LT Brown left for Tokyo via Pusan. The breakdown of negotiations was the first of many. The prevailing excuse was alleged “UN violations” of the Communist-controlled “neutral” Kaesong perimeter.14

By then, the 1st RB&L ADVON OIC, Captain Frederick P. Laffey, had arranged to co-locate 3rd Repro at the nearest FECOM print facility, the Printing and Publications Center in Motosumiyoshi, a suburb of Kawasaki, halfway between Tokyo and Yokohama. The 3rd Repro would remain assigned to 1st RB&L.15 Thus, when the USNS General A.W. Brewster docked at the Yokohama pier, the three officers and fifty-four men of the 1st RB&L print unit were loaded aboard busses to Kawasaki while the rest of the Psywar group went to Tokyo.16

Necessity drove the requirement to dedicate a Psywar officer to cover Armistice negotiations activities at Kaesong, and then Panmunjom. While it was tedious duty, the Communist use of sympathetic Western correspondents had to be countered by official UN reporting. A state of Cold War between West and East was now acknowledged. Americans at home faced a Congressionally-instigated, FBI-supported Red Scare that proved worse than the one after WWI. Since the Chinese intervention in late November 1950, the UN Security Council, again having Soviet representation, sought to end the fighting in Korea. Restoration of the status quo antebellum north-south boundary along the 38th Parallel became the UN objective. Continual reunification rhetoric by President Syngman Rhee was regularly tamped down by the Americans to do this. Awaiting LTC Homer Shields’ arrival were the challenges of establishing Voice of the UN Command (VUNC) using Radio Tokyo broadcasting time and the rebuild and oversight of the Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) in Korea.

![The Eighth Army [EUSA] 217th Car Company was dedicated to transport Allied military representatives and UN correspondents to and from the negotiations site. All vehicles had white flags conspicuously mounted.](https://arsof-history.org/articles/images/v7n2_1st_rbl_advance/400/car_company.jpg)