DOWNLOAD

In October 1950, the Army Navy Air Force Journal reported that “while plans for psychological warfare in a future emergency have been in progress for the past five years … they were undoubtedly speeded up because of the Korean crisis.”1 However, the claim of progress in planning for psychological warfare after World War II was a gross exaggeration. As a capability, psychological warfare (Psywar) was nearly non-existent after WWII. Only the U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) had any real capability in the radio broadcasting arena.

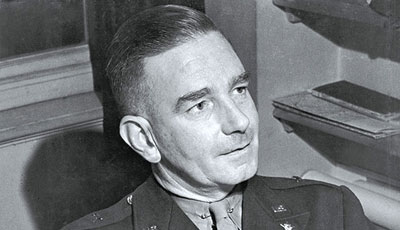

Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, the Chief of Psychological Warfare in the Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) during WWII, had advocated for Psywar with an aggressive letter-writing campaign since 1946, but saw little result for his efforts. In August 1950, Major General (MG) Charles L. Bolte, Army G-3, called McClure to the Pentagon to discuss rebuilding the Army’s Psywar capability. Pressured by Secretary of the Army Frank Pace, the G-3 established a Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) two months after war broke out in Korea.2

BG McClure’s WWII experience as head of censorship, publicity, and psychological warfare, and his postwar experience as chief of information control and re-education in Germany, made him the obvious candidate to rebuild the U.S. Army’s Psywar capability. As Chief of the Psychological Warfare Division, G-3, he had three overarching priorities that he addressed simultaneously. First, he wanted to elevate the PWD to Special Staff status at the Pentagon. Second, he needed to coordinate with Headquarters, Army Field Forces (AFF), Fort Monroe, Virginia, to activate new tactical and strategic Psywar units from existing Tables of Organization and Equipment (T/O&E) and Tables of Distribution (T/D). Finally, the new units had to be manned, trained, equipped, and deployed to theater commands and field armies in the Far East and Europe.

Initially, BG McClure had few resources to accomplish these critical tasks other than the lessons of WWII. For organization, troop strength, and equipment for Psywar units, he referenced T/O&E 30-47, dated 15 December 1943 and amended on 22 June 1944. These documents established the template for the Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company (MRBC) and provided for twenty officers and one hundred-forty enlisted soldiers (including linguists, radio operators and engineers, printers, loudspeaker announcers, and others), twenty-four trucks ranging in size from quarter-ton to two and a half-tons, two Davidson Duplicator Presses, SCR-696 and SCR-698 Radio Sets, four AN/UIQ-1 Public Address Sets, and other mission-essential equipment.3 This T/O&E provided Psywar planners the starting point from which to man and equip new units.

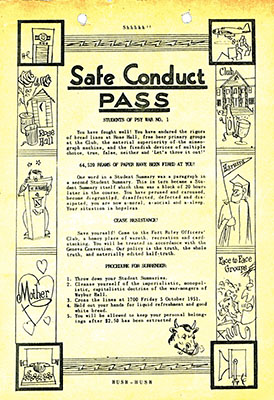

In addition to T/O&E 30-47, McClure examined some of the Psywar studies conducted by the Army in the interwar period, which also focused on the organization and operations of WWII MRBCs.4 In September 1947, the Department of General Subjects (DGS), Intelligence School at the Army Ground General School, Fort Riley, Kansas, completed the study Tactical Psychological Warfare. The report determined that radio was “a strategic weapon and had no place in a purely tactical psychological warfare unit.” It also recommended that the War Department establish a provisional Psywar unit called a Combat Psychological Warfare Detachment (CPWD) for “purely tactical operations.” The CPWD would employ loudspeakers and leaflets, though “higher headquarters” might permit them to use mobile short-range radios.5

The total number of personnel within the proposed CPWD’s subordinate sections (Headquarters, Intelligence, Publications, and Loudspeaker) was eleven officers and eighty enlisted personnel. The provisional unit loosely resembled the structure of the future Loudspeaker and Leaflet (L&L) Company. The 1947 report revealed the Intelligence School’s initiative in developing Psywar organization and doctrine, and influenced BG McClure’s selection of Fort Riley for a Psychological Warfare Division and School in 1950.

Prior to September 1950, the U.S. Army only had seven experienced Psywar officers on active duty and one twenty-four-man Tactical Information Detachment (TID), activated at Fort Riley in June 1947. In 1950 the Army General School assumed operational control over the TID with the 47th Army Engineer Camouflage Battalion supervising its training. In May 1950, the TID transferred to the Army General School (AGS), 5021st Army Special Unit (ASU), for administration, quarters, and rations.6

By late-September, United Nations forces were sweeping northward up the Korean peninsula. As Chief, PWD, BG McClure’s most pressing issue was deploying a tactical Psywar unit to the Far East Theater of Operations. Assured that additional personnel and equipment would arrive soon, the understrength, underequipped, and minimally trained TID deployed to support Eighth U.S. Army (EUSA) in Korea in October 1950. So that its organizational and operational needs would be met, the TID was re-designated the 1st L&L Company in November 1950.7 With the TID/1st L&L awaiting more personnel and equipment in Korea, McClure shifted focus to the complicated tasks of organizing, manning, training, equipping, and eventually deploying additional Psywar units. To overcome the obvious shortage of personnel and units in the active component, he turned to the U.S. Army Reserve (USAR).

Although the Army had inactivated all of its Psywar units after WWII, the U.S. Army Reserve had demonstrated better foresight. In 1947, Colonel (COL) Garland H. Williams, a veteran of the Office of Strategic Services and commander of the 1173rd Military Intelligence Group (USAR) in New York, established a Psywar Section. On 22 November 1947, COL Ellsworth H. Gruber, an intelligence officer during WWII and printing supervisor at the New York Daily News, assumed command of the section. On 21 June 1949, the 1588th Psychological Warfare Battalion (Training) replaced the 1173rd’s Psywar Section and absorbed its personnel, including COL Gruber. A year later, 1588th personnel transferred to the 1118th Organized Reserve Army Service Unit, Army Field Forces Intelligence School. With COL Gruber still in command, the detachment formed a Special Projects Branch within the school.8 These units were further augmented by civilian companies that could form Psywar units in the USAR.

Participating in the Army’s post-WWII Industrial Affiliation Program, private sector companies formed reserve units from their pool of existing employees. The program’s intent was to have trained personnel available for activation into Federal service. First Lieutenant (1LT) Robert M. Zweck, employee at the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), believed that the Industrial Affiliation Program better prepared the Army for war. When federalized, company-specific reserve units “wasted no time. Guys suddenly took off one set of clothes, put on another, and [they were] ready to go.”9

David Sarnoff, Chairman of the Board of Radio Corporation of America, founder of NBC, and former general officer assigned to SHAEF during World War II, petitioned the Army to activate the 406th MRBC in the USAR, which it did on 15 November 1948.10 Captain (CPT) William B. Buschgen, commander of the 406th MRBC, and other employees from NBC drilled monthly in New York City.11 The 406th provided the core of enlisted personnel for the MRBC of the 301st Radio Broadcasting & Leaflet (RB&L) Group, activated in the USAR in October 1950.12 Dated May 1950, Tables of Distribution 250-1201, 250-1202, and 250-1203 provided the template for the 301st RB&L’s Headquarters, Reproduction (Repro), and Mobile Radio Broadcasting Companies.13 With the 301st established in the USAR, BG McClure received approval to activate the 1st RB&L in November 1950. Consisting of the Headquarters Company, the 3rd Repro, and the 4th MRBC, the 1st RB&L trained at Fort Riley until it deployed to Far East Command (FECOM) in August 1951. The RB&Ls became strategic assets at the Theater Command level.

On 1 September 1950, the Department of the Army published T/O&E 20-77 for the tactical L&L Company. Consisting of a Headquarters section, three platoons (Publications, Propaganda, and Loudspeaker), and eight officers and ninety-nine enlisted soldiers, the L&L became a field army asset like the WWII MRBCs.14 T/O&E 20-77 allotted each L&L eighteen M38 quarter-ton trucks, nine two and a half-ton “vans,” three Davidson Model 221 lithographic presses, two LS-111/UIQ-1 loudspeaker systems, twelve AN/UIQ-1 public address sets, five AN/VRC-10 and two SCR-244 radios. McClure received approval from Army Field Forces to activate the 1st and 2nd L&Ls in November 1950 and the 5th L&L in March 1951 with the necessary equipment, but at reduced strength levels.15

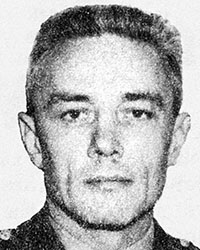

As Chief of the PWD, Army G-3, BG McClure cooperated closely with the Psychological Warfare Division, G-2, AFF, though he exercised no command or control over it. The Chief of the PWD, AFF, COL Donald F. Hall, had served as commander of the 2679th Headquarters Company, Psychological Warfare Branch (PWB), Allied Force Headquarters and later as the Military Director of the PWB during World War II.16 Under Hall were WWII Italian campaign veterans Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Frank A. McCulloch, former commander of 2nd Battalion, 135th Infantry Regiment, 34th Infantry Division, and LTC John O. Weaver, former commander of Fifth Army’s Combat Propaganda Team.17 Working together, BG McClure, COL Hall, and their respective divisions spent the rest of 1950 establishing a Psychological Warfare Division and School at the AGS, Fort Riley. This required approval from Army Field Forces.