ABSTRACT

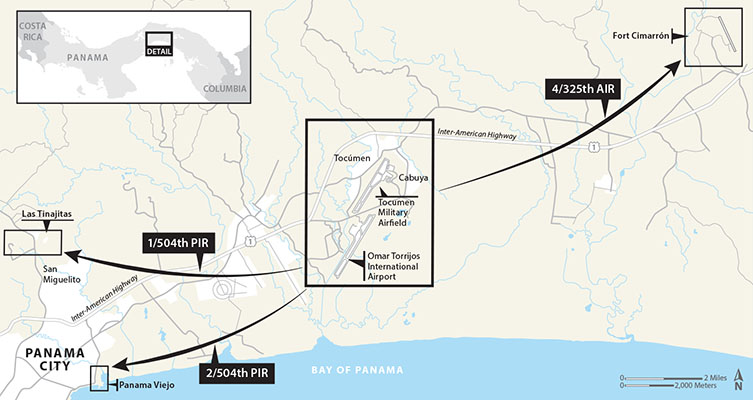

Since May 1989, there had been a Psychological Operations (PSYOP) tactical loudspeaker detachment in Panama. However, additional loudspeaker teams were needed to join combat forces for Operation JUST CAUSE, starting on 20 December 1989. 1st, 6th, and 8th PSYOP Battalion soldiers got the job of supporting the 75th Ranger Regiment and 82nd Airborne Division assault on the Torrijos-Tocumen airport complex. Two such teams surmounted unique challenges in an effort to save American and Panamanian lives during the violent opening hours of combat in Panama.

NOTE

This article is part of our series on Operation JUST CAUSE. For a background on Special Operations's involvement in JUST CAUSE, read The Path to War in Panama.

TAKEAWAYS

- Despite similar D-Day/D+1 missions for the two tactical loudspeaker elements discussed here, variations (some of them considerable) existed between them.

- On 20 December 1989, regionally-aligned, language-capable soldiers from 1st POB were effective at talking with civilians, sorting out the confusion around Torrijos-Tocumen.

- While loudspeaker teams proved valuable to their supported units, overall, the man-packed and vehicle-mounted loudspeakers themselves were ineffective at the outset of JUST CAUSE: (1) the bulky AN/UIH-6s were unneeded at Torrijos-Tocumen because combat arms units so rapidly achieved their objectives; (2) the AN/UIH-6s were not taken initially to Tinajitas; and (3) the HMMWVs containing the AN/UIH-6As were not recovered post-drop until days later.

- Tactical loudspeaker soldiers meeting their supported units on the plane ride to a combat zone was not a recipe for success; while they adapted to their circumstances, pre-mission planning and rehearsals are critical to developing interoperability, particularly for units like the 82nd Airborne Division, which may not routinely work with PSYOP assets.

DOWNLOAD

At 1145 hours on Monday, 18 December 1989, First Lieutenant (1LT) Robert E. Gagnon, the Audio/Visual (A/V) Platoon Leader, 8th Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Battalion (POB), 4th PSYOP Group (POG), Fort Bragg, North Carolina, received the alert for deployment. Assigned to him was an ad hoc team of eight non-Spanish speaking soldiers from 8th POB and 6th POB. They reported to the battalion motor pool to prepare three M-1025/1026-series High-Mobility Multipurpose Wheeled Vehicles (HMMWVs) for movement, placing in each a mountable 450-watt AN/UIH-6A loudspeaker. Team members packed clothing and personal equipment into rucksacks, and drew M16A2 rifles, protective masks, and four 250-watt AN/UIH-6 loudspeaker systems.1 Despite having been on standby, 1LT Gagnon was not “really sure what was going on … [W]e were told we were going to take part in an exercise with the 82nd Airborne Division.”2 Operational security had been of paramount concern.

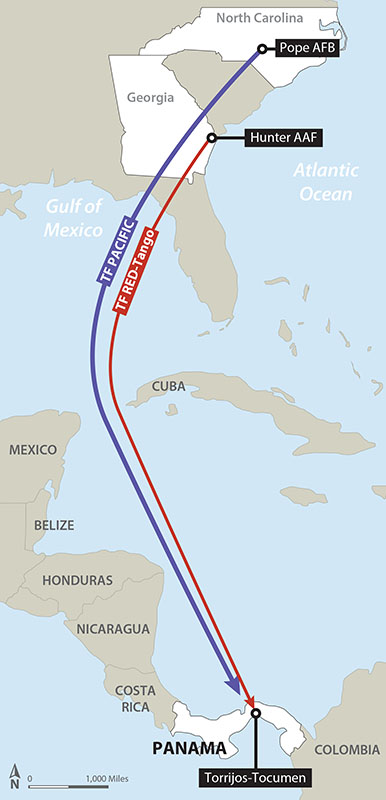

Unbeknownst to these soldiers, U.S. President George H.W. Bush had just ordered the invasion of Panama to protect U.S. lives and property; remove dictator Manuel Noriega, the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF), and Dignity Battalion (DIGBAT) goon squads; restore law and order; and support a U.S.-recognized government in Panama.3 Lieutenant General (LTG) Carl W. Stiner, Commanding General, XVIII Airborne Corps, was directed by the Joint Chiefs of Chief to execute Operation Plan 90-2, the tactical plan for the U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) Operation Order 1-90 (BLUE SPOON, which became JUST CAUSE). XVIII Airborne Corps assumed the lead as Joint Task Force (JTF)-South.4

Units already in Panama, including the 7th Infantry Division (ID), 193rd Infantry Brigade (Task Force [TF] BAYONET), 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines (TF SEMPER FI), and 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (TF BLACK), prepared for offensive operations. At the same time, Continental U.S. (CONUS)-based forces including U.S. Army Rangers (TF RED), U.S. Navy SEALs (TF WHITE), and the 82nd Airborne Division (TF PACIFIC) mobilized for a synchronized invasion. These combat forces were supported by PSYOP loudspeaker teams from 4th POG, at least one two-man team per battalion. As CONUS units scrambled to mobilize on 18 December, JTF-South Forward deployed to Panama, moving into U.S. Army, South (USARSO) Headquarters at Fort Clayton. That afternoon, LTG Stiner and his principal staff arrived to assume command of JTF-South.5