From Veritas, Vol. 15, No. 1, 2019

ABSTRACT

Frequent training between the 617th Special Operations Aviation Detachment and 3rd Battalion, 7th Special Forces Group (3-7th SFG) in the months prior to Operations JUST CAUSE and PROMOTE LIBERTY laid the foundation for the accomplishment of key high-risk missions in Panama. Refined tactics, mutual trust, and interoperability were central to special operations successes during the U.S. invasion and stabilization of the Central American country from 20 December 1989 to 31 December 1990.

NOTE

This article is part of our series on Operation JUST CAUSE. For a background on Special Operations's involvement in JUST CAUSE, read The Path to War in Panama.

TAKEAWAYS

- Forward stationing allowed the 617th SOAD and 3-7th SFG to rehearse missions, leading to important lessons learned, refined tactics, and trust between the special operations ground force and aviation units

- The use of conventional and USAF rotary wing assets allowed the 617th to focus on special operations-specific missions45

- Special Operations rotary wing capabilities were essential to the success of the Radio Nacional mission during Operation JUST CAUSE

DOWNLOAD

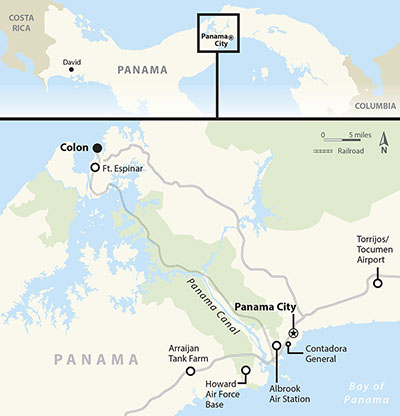

On 20 December 1989, thirty-three Special Forces (SF) soldiers from Company C, 3-7th SFG fast roped onto the roof of the Contraloria General building to stop radio broadcasts encouraging violence against U.S. forces during the early hours of Operation JUST CAUSE.1 The mission required precision flying in dangerous conditions. Several weeks later, Operational Detachments-Alpha (ODAs) from 3-7th SFG established a forward operating base south of the Cordillera de Talamanca mountain range, from where they conducted stability operations in the area around David. Getting to David required a high risk flight across the mountains, descending through heavy cloud cover over the Pacific Ocean.2 Success in those missions was largely dependent on established interoperability with the 617th Special Operations Aviation Detachment (SOAD).

The 617th was a company of five MH-60A Black Hawk helicopters operationally controlled by, and stationed in Panama with Special Operations Command-South (SOCSOUTH).3 Activated in October 1987, it provided the majority of Army Special Operations Aviation support to the theater special operations command’s special operations forces (SOF), which included 3-7th SFG.4 In September 1989, the 617th was reorganized and administratively placed under the newly established 3rd Battalion, 160th Aviation.5

Despite being stationed on opposite sides of the isthmus, and nearly continuous deployment schedules, the 617th and 3-7th SFG built strong rapport over a period of nearly three years.6 The units had a habitual, nearly daily working relationship, and the 617th often left two Black Hawks and crew with 3-7th SFG at Fort Espinar, where they trained on urban operations, fast roping, precision fires, and vehicle interdiction.7 Underscoring the consistency of the relationship, then-Captain (CPT) Mark B. Petree, a detachment commander in Company C, 3-7th SFG, remembers being “in a 617th helicopter at least once a week.” Then-CW2 Daniel Jollota, a fully mission qualified 617th pilot, recalls training with 3-7th SFG from 1987 to 1989, “three or four times a week, mostly at night.”8 In addition to training, the units upgraded fast rope equipment; revised tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs); and conducted missions throughout the hemisphere.9

As tensions increased between U.S. forces stationed in Panama, and the Panamanian Defense Forces (PDF) under the control of dictator Manuel Noriega, those missions came closer to home. In the spring of 1988, 3-7th SFG established observation posts in the jungles “around the Arraijan Tank Farm, adjacent to Howard AFB,” the 617th’s home station.10 From there, they observed the infiltration routes of armed Panamanians into the area.11 On one occasion, the 617th and the C/3-7th SFG quick reaction force launched to support ground forces in contact with armed intruders, suspected to be Cuban special forces and pro-Noriega Panamanians. Similar missions were conducted near Fort Espinar, where 3-7th captured intruders near dependent housing areas.12 Co-located in helicopter hangars and shoot houses during those missions, the 617th and 3-7th SFG safeguarded U.S. installations and gained experience operating together, especially at night.13

The 617th and 3-7th SFG had been preparing for combat operations in Panama since late-1987. Early rehearsals for missions that became part of Operation Plan (OPLAN) BLUE SPOON, later renamed JUST CAUSE, laid the groundwork for success when the invasion was launched.14 Specifically, the 617th used Forward Looking Infrared (FLIR) and gun reconnaissance video to collect intelligence for the OPLAN.15 In the summer of 1989, the units began training together more frequently.16 After a failed coup to remove Noriega on 3 October 1989, Task Force (TF) BLACK was established “to plan, coordinate and execute assigned tasks under OPORD 2-90 BLUE SPOON.”17

Mission-specific training between the 617th and 3-7th SFG increased to several times per week in November 1989 as planning was refined. Then- C/3-7th SFG commander, Major (MAJ) David E. McCracken noted, for example, that the rescue of American Kurt Muse from Modelo Prison was considered a critical mission prior to a full-scale invasion. McCracken noted that “the 617th was the only capability to support insertion for the rescue.”18 Rehearsals for combat operations included flying routes later used to subdue the PDF, “inserting 3-7th SFG detachments on critical targets,” including “water tanks, a school, and an old hospital,” and “dispersed insertions of C/3-7th SFG to secure the three individuals elected by the Panamanian people to govern the country.”19

The rehearsals also provided critical lessons learned. Training insertions, for example, helped the 617th and 3-7th SFG establish standard operating procedures (SOPs) for internal communications on the Black Hawks. Anticipating planned missions, 617th and 3-7th SFG rehearsals helped determine how quickly the ground force could disembark the helicopters on small, high platforms.20 In addition, rehearsals led to the development of physical infrastructure used on D-Day, such as map boards, communications gear, and wiring for antennas.21

One challenge that the units faced in late December was a demand for special operations aviation that exceeded the 617th’s capacity. Despite being manned at roughly half of what was allocated in the Table of Organization and Equipment, the 617th was tasked with supporting special operations missions for other task forces, in addition to its formal placement in TF BLACK.22 Because of the need for crew rest, coupled with the 617th’s small number of helicopters and limited manpower—the unit had only ten pilots in Panama—7th SFG used conventional assets and U.S. Air Force (USAF) helicopters to supplement their dedicated special operations aviation support.23

3-7th SFG used MH-53s Pave Lows from the USAF 1st Special Operations Wing for larger troop movements, and two UH-60 helicopters provided by 1st Battalion, 228th Aviation Regiment, when 617th assets were unavailable.24 Conventional and USAF units performed well during JUST CAUSE, but the 617th’s close relationship with 3-7th SFG, and its special operations capabilities, gave the ground force the confidence to conduct missions they would not have attempted with other units.25 Thus, the use of conventional and USAF units in TF BLACK allowed the 617th to focus on missions where its SOF-specific capabilities were essential.

By the time Operation JUST CAUSE began, Howard Air Force Base had become overcrowded with units from several task forces. For that reason, and because he determined that co-location with 3-7th SFG would enhance operational planning, then- Major (MAJ) Richard D. Compton, the 617th SOAD commander, moved his unit to Albrook Air Base soon after H-Hour. While advantageous operationally, Albrook’s proximity to unsecured areas occasionally led to tense situations. In one instance, Colonel (COL) Robert C. Jacobelly, the SOCSOUTH commander, was nearly hit by a round fired into the operations center.26 Risks aside, the 617th did not incur casualties at Albrook, and co-location with the ground force enhanced mission planning.

The 617th flew multiple insertions of Special Forces ODAs prior to H-Hour, and numerous combat missions for TF BLACK over the course of two weeks.27 It provided airlift; infiltrated and recovered ODAs during direct action raids; and flew casualty evacuation, reconnaissance, surveillance, and interdiction missions. At times, the 617th’s unique capabilities and experience working with Special Forces were key to mission success.28 One such mission was the assault on Radio Nacional, which took pro-Noriega broadcasts off the air.

MAJ McCracken noted that his “absolute confidence” in the aviators was critical to the assault on Radio Nacional, both in the decision to conduct the mission, and in its success.29 Only the 617th was fast rope capable, and the years of operating with 3-7th SFG enabled speed and precision during infiltration and recovery of ground forces during the operation. McCracken noted that the two units’ preparedness was a result of having trained on platform infiltrations during the lead-up to JUST CAUSE.30

617th SOAD pilots delivered the ground force to their target and held steady as the SF team fast-roped to the small roof on top of the seventeen-story Contraloria General building, amidst swirling winds and low-level light.31 From there, the assault team shut down propaganda broadcasts transmitted on AM radio that encouraged Panamanians to take up arms against U.S. forces. The 617th was also far more experienced with night vision goggles (NVGs) than other units, which was critical, since the mission unfolded in late-evening of the shortest day of the year. After a quick return to Albrook under NVGs, they re-launched, again under NVGs, to neutralize the FM antenna at Hippodrome, east of Panama City.32 Ultimately, MAJ McCracken attributed much of his team’s success in securing the Radio Nacional building to the 617th’s proficiency operating in the most difficult conditions—at dusk and in shifting winds; and during the exfiltration, under NVGs.

At the outset of hostilities, the 617th was primarily assigned to support C/3-7th SFG, with three of the detachment’s Black Hawks committed to the company during initial combat operations.33 While C/3-7th SFG was the 617th’s priority ‘customer’, the unit began operating as five separate helicopters after the first 48-hours, based on ad hoc tasking from TF BLACK.34 It supported Company A, 3-7th SFG in blocking PDF reinforcements at Pacora River Bridge, and helped safeguard Noriega’s imprisoned opponents who had been identified as key leaders in the new government.35 By early January, 3rd Battalion, 160th Special Operations Aviation Group sent several pilots and crew, and a Black Hawk, to augment the 617th.36

During Operation PROMOTE LIBERTY, the stability operations that began just after H-Hour and continued throughout 1990, the 617th transported and resupplied ODAs and Military Intelligence-Civil Affairs (MICA) teams around the country.37 The 617th’s experience with internal fuel tanks was critical in those missions, which included collecting weapons and narcotics from rogue elements.38 7th SFG missions to Penonomé and David, for example, were possible because internal fuel blivets, unique to MH-model Black Hawks, allowed the 617th to transport the ground force to the target without refueling.39

The month-long mission to David, in particular, demonstrated the contributions of the 617th to special operations in Panama. Located in the northwestern part of the country, David was a stronghold of pro-Noriega PDF. In the first few days of the invasion, the 617th helped the Rangers from 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment manage the surrender of the PDF in David and capture a weapons cache north of the city, and 3-7th SFG secure Lieutenant Colonel Luis del Cid, a key aide to Noriega.40 Then, in late-December, ODAs from A/3-7th SFG, and one 617th Black Hawk, with two pilots and two crew members, set up on a local airfield just over the mountains from David, from where they conducted “clearing” operations to subdue the remaining PDF soldiers.41

Almost every day for a month, the 617th transported ODAs north over the Cordillera de Talamanca mountain range to David. The flight required 617th pilots to descend through heavy cloud cover over the Pacific Ocean, with no instrumentation, before turning east toward the city. The small Panamanian airport provided the only fuel, and the pilots had no direct communication with their chain of command at Albrook. Years of training together made the units interoperable, and the 617th crew was able to work efficiently under A/3-7th SFG, speaking only rarely with MAJ Compton through their Special Forces partners. Despite the austere conditions, the units completed their mission, and the remaining PDF forces were subdued.42

Tactical familiarity between special operations aviation units and ground forces, and habitual relationships that streamlined the process for conducting missions, contributed to Army special operations forces’ success during operations in Panama.43 While the 617th had a small footprint, it played a critical role in several key missions during the conflict. 617th pilots received Army Air Medals for their efforts, though their contributions to Operations JUST CAUSE and PROMOTE LIBERTY are best reflected in the views of the ground force units that they supported. In summarizing the invasion, now-retired COL McCracken stressed the extent of 617th support to his company. They “earned DFCs [Distinguished Flying Crosses],” he emphasized, “whether they received them or not.”44

ENDNOTES

- LTC David E. McCracken, Memorandum for Curator, U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School Museum, “SUBJECT: Note of Explanation with Company Guidon-C-3-7th SFG,” 14 July 1992, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC; Email from COL (Ret.) David E. McCracken to Robert D. Seals, “SUBJECT: Initial Items for C/3-7th SFG Vignette,” 26 January 2019, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- CW5 (Ret.) Daniel Jollota, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 18 June 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Jollota interview, 18 June 2019. [return]

- Kenneth Finlayson, “A Tale of Two Units: The 129th Assault Helicopter Company,” Veritas: Journal of Army Special Operations History, 3:1 (2007), 69. [return]

- Pilots, crew, and maintainers from the 129th Special Operations Aviation Company, Hunter Army Airfield, GA, deployed to Panama on four to six month rotations to fill out the 617th, until the detachment received its own aircraft and official manning in March 1989. CW5 (Ret.) Charles Lapp, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 12 July 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Lapp interview, 12 July 2019; Finlayson, “A Tale of Two Units,” 70. [return]

- The 617th SOAD was initially part of the 129th Aviation Company, headquartered at Hunter Army Airfield (AAF), GA. The 129th was inactivated in 1989, with assets transferring to the newly constituted and activated 3rd Battalion, 160th Aviation. See: Department of the Army General Order No. 3, “Organizational Actions of Units to Form the 160th Aviation Regiment Under the U.S. Army Regimental System (USARS),” 16 January 1988, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. In 1995 the 617th became Company D, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR), and in 2003 it relocated to Hunter AAF alongside 3/160. It was reorganized into the headquarters and headquarters company (HHC) for the newly established 4th Battalion, 160th SOAR (4/160) in 2007. While the 617th manpower and platforms were eventually used to establish HHC/4/160, Company C, 3/160 retained the mission to support U.S. Southern Command. [return]

- LTG (Ret.) Charles T. Cleveland, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 16 May 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; COL (Ret.) Bruce P. Yost, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 20 May 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Yost interview, 20 May 2019. COL (Ret.) Mark B. Petree, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 12 June 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Petree interview, 12 June 2019. [return]

- Petree interview, 12 June 2019; Compton interview 12 March 2019; COL (Ret.) David E. McCracken interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 14 May 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter McCracken interview, 14 May 2019; CW3 (Ret.) Bradley Smith, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 21 May 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Smith interview, 21 May 2019. [return]

- Petree interview, 12 June 2019; Jollota interview, 18 June 2019. [return]

- Petree interview, 12 June 2019. [return]

- Email from COL (Ret.) David E. McCracken to Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, “SUBJECT: E-Intro for some 17th SOAD Info~RE: 7th SFG and Aviation in Panama, Tuesday,” 17 July 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter McCracken email, 17 July 2019. [return]

- The intruders were suspected to be Panamanian Defense Forces, and/or Cuban Special Forces. See: Lawrence A. Yates, The U.S. Military Intervention in Panama: Origins, Planning, and Crisis Management, June 1987-December 1989 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2008), 77; Smith interview, 21 May 2019. [return]

- Fort Espinar was a Panamanian-controlled installation. Prior to U.S.-Panamanian treaty provisions in the late-1970s, it was a U.S. base, Fort Gulick. As a result, numerous U.S. family housing units, the commissary, and gas station remained on Fort Espinar after it was turned over to Panamanian control. See: McCracken email, 17 July 2019. [return]

- Petree interview, 12 June 2019. [return]

- Operation BLUE SPOON aimed at removing Noriega, subduing the PDF, and securing the Panama Canal. [return]

- Petree interview, 12 June 2019. [return]

- Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019. [return]

- TF BLACK Mission Statement and Activities AAR, undated, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. “TF BLACK was re-designated Joint Special Operations Task Force-Panama” on 16 January 1990. [return]

- McCracken email, 17 July 2019. The exact amount of training is unclear. Individuals involved recall different rates of training, from daily to once a week. It seems likely that the training pace increased markedly at after the failed October coup. COL (Ret.) Robert G. Louis interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 8 May 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Louis interview, 8 May 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019; Dolores de Mena, Command Historian, U.S. Army South, Annual Command History, Operation JUST CAUSE/PROMOTE LIBERTY Supplement, Fiscal Year 1990, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- McCracken email, 17 July 2019; COL (Ret.) Richard D. Compton, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 7 June 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; International Delegation Report, “The May 7, 1989 Panamanian Elections,” 1989, Copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC; COL (Ret.) David E. McCracken, Radio Nacional mission questionnaire, 2 August 2019, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; Email from COL (Ret.) David E. McCracken to Mr. Robert D. Seals, “SUBJECT: Even More ‘Parameters’ for C-3-7 Vignette,” 29 January 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter McCracken email, 29 January 2019. [return]

- Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; Yost interview, 20 May 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Louis interview, 8 May 2019. General Maxwell R. Thurman, SOUTHCOM commander, instituted a tour length change for U.S. forces in Panama after the failed 1989 coup, resulting in an early permanent change of station (PCS) for nearly a thousand soldiers, sailors, marines, and families. See: U.S. Southern Command, CY89 Annual Historical Report, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. The shift in manpower happened so quickly, however, that replacements had not arrived prior to the execution of Operation JUST CAUSE. See: Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Jollota interview, 18 June 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- Yates, Operation JUST CAUSE, December 1989-January 1990, 210-211; Louis interview, 8 May 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; Yost interview, 20 May 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; 8 May 2019; Darrel D. Whitcomb, On a Steel Horse I Ride: A History of the MH-53 Pave Low Helicopters in War and Peace (Maxwell AFB, AL: Air University Press, 2012), 270; U.S. Special Operations Command, 10th Anniversary History, copy in USASOC History Office, 31-34. [return]

- McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Yates, Operation JUST CAUSE, December 1989-January 1990, 219. [return]

- TF BLACK Mission Statement and Activities AAR, undated, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC; MAJ Richard D. Compton, 617th Special Operations Aviation Commander, After Action Report and Lessons Learned, undated, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC, hereafter Compton AAR; Compton interview, 12 March 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019; Louis interview, 8 May 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June, 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019. [return]

- McCracken email, 29 January 2019; Louis interview, 8 May 2019. [return]

- McCracken email, 29 January 2019; Jollota interview, 18 June 2019. [return]

- McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- MAJ David E. McCracken, Memorandum for Commander, 3-7 SFG, “SUBJECT: Team Charlie Special Operation-Radio Nacional Antenna, 21 December 1989,” USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- Compton interview 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; After Action Report, Cerro Azul Mission, Operation JUST CAUSE, 19-26 December 1989, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC; Lawrence A. Yates, The U.S. Military Intervention in Panama: Operation JUST CAUSE, December 1989-January 1990 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2014), 210-222. [return]

- Lapp interview, 12 July 2019. [return]

- Compton interview, 12 March 2019; Compton interview, 7 June 2019; Smith interview, 21 May 2019; McCracken interview, 14 May 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019; After Action Report, Cerro Azul Mission, Operation JUST CAUSE, 19-26 December 1989, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC; Lawrence A. Yates, The U.S. Military Intervention in Panama: Operation JUST CAUSE, December 1989-January 1990 (Washington D.C.: Center of Military History, 2014), 210-222. [return]

- Compton interview, 7 June 2019. The 228th Aviation Regiment began fielding an Extended Range Fuel System in 1989. See: Specialist Frank L. Marquez, “UH-60s getting long range fuel tanks,” Tropic Times, 21 July 1989, copy in USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- Memorandum from COMJTFSO to USCINCSOUTH, “Subject: Success List—As of 260700R Dec 89,” 26 December 1989, Folder-“Success List 21 Dec 89-10 Jan 90,” Box 2, Yates Collection, Combined Arms Research Library, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas; Jollota interview, 18 June 2019; Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019. Del Cid’s surrender was significant, as he agreed to testify for the prosecution in U.S. federal court against Noriega, who was convicted on drug trafficking charges in April 1992. See: Robert L. Jackson, “Noriega Took Drug Funds, His Ex-Aide Testifies,” Los Angeles Times, 18 September 1991, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1991-09-18-mn-2249-story.html, accessed 9 July 2019; Mike Clay, “Key Witness Against Noriega Sentenced to Time Served,” Los Angeles Times, 10 July 1992, https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1992-07-10-mn-1863-story.html, accessed 9 July 2019. [return]

- Jollota interview, 18 June 2019; COL (Ret.) Richard D. Compton, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 26 June 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Jollota interview, 18 June 2019; COL (Ret.) Richard D. Compton, interview by Dr. Joshua D. Esposito, 26 June 2019, USASOC History Office Classified Files, Fort Bragg, NC. [return]

- Cleveland interview, 16 May 2019. [return]

- McCracken interview, 14 May 2019. [return]

- Whitcomb, On a Steel Horse I Ride, 263-275; Yost interview, 20 May 2019; Louis interview, 8 May 2019. [return]