SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

El Salvador, one of the smallest (geographically, the size of Massachusetts) and most densely populated countries in the world, was plagued by organized insurgency for thirteen years during the 1980s and early 1990s. Throughout that conflict Army special operations forces (ARSOF) did an exceptional job, performing a wide variety of foreign internal defense (FID) missions to support U.S. Military Group (MILGP) efforts to help the Salvadoran government fight its counterinsurgency (COIN) war. Professional relationships with the armed forces of Latin America were established by Special Forces (SF) teams in the 1960s, when Communists were fomenting “wars of national liberation” throughout the region.

The purpose of this article is to explain the 8th SF Group [Special Action Force Latin America (SAFLA)] mission to provide airborne Ranger infantry training to a select group of Salvadoran officers and sergeants in 1963. These leaders were slated to cadre the first airborne company in the armed forces of El Salvador (ESAF). It proved to be the first COIN training for the Salvadoran military and the airborne Ranger graduates were instrumental in raising the level of professionalism of the ESAF. Some from this original group later commanded with distinction during the thirteen-year war against the rebel FMLN (Frente Farabundo Marti de Liberación Nacional). But, the impact of this specialized training was not realized by the SF Operational Detachment Alpha (ODA) commander at the time.

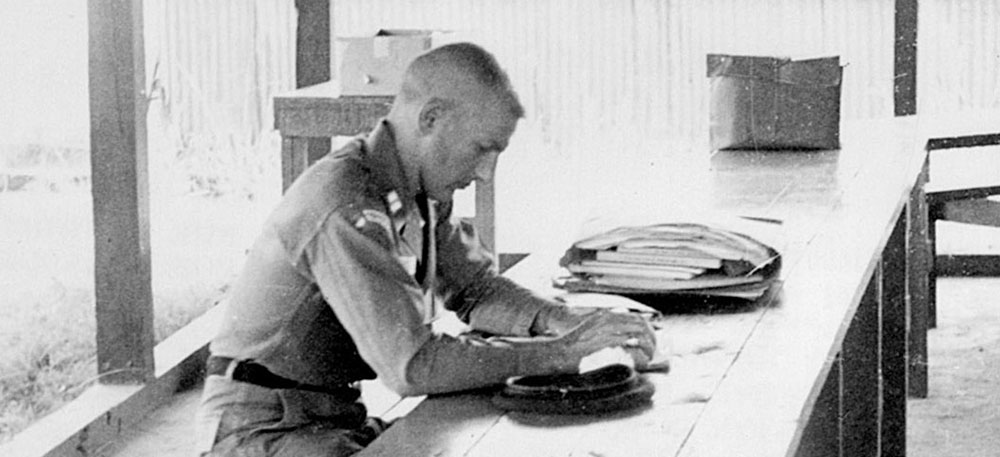

Captain (CPT) Richard F. Carvell, ODA-3 commander, A Company, 8th Special Forces Group (SFG), 1st Special Forces (SAFLA) had led a MTT (mobile Training Team) to Chile from September through December 1962 to train a Commando force. The commendation letters for that mission had just filtered down to 8th SFG headquarters when Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Arthur D. “Bull” Simons, the group commander, gave Carvell the mission to conduct a Ranger course for a select group of Salvadoran officers and sergeants arriving on 2 May 1963. Training was originally to begin on 6 May. The ODA-3 members scrambled to prepare a program of instruction (POI), publish a training schedule, and translate lesson plans and handouts into Spanish. The team had to assemble training aids and special equipment, arrange medical support, request ammunition and explosives, transportation, and training areas for the Salvadoran group.1

The ODA-3 commander had several advantages. As a private, Carvell had received six weeks of Ranger training, the Infantry School standard POI for Airborne Ranger companies during the Korean War and had served in combat with the 1st Airborne Ranger Company. CPT Carvell was just finishing two years as a Lane Instructor (LI) in the Ranger Department (Fort Benning phase) when LTC Simons came recruiting for SF. And, the Chilean Commando course POI in Spanish that he conducted six-months earlier was a compressed version of the nine-week U.S. Army Ranger course.2

The training was part of the Alliance for Progress initiated by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, and followed the Cuban Missile Crisis in October 1962. It was designed to prepare Latin American militaries to combat the rise of Communist-inspired insurgencies in the region and to professionalize their officer and emerging NCO corps. In the initial years of the Alliance, the United States government gave more weight to economic assistance and social reforms than military aid to counter insurgency. Since El Salvador was becoming the dominant economic power in Central America, its military leaders were receptive to training special elements to combat insurgent threats.3

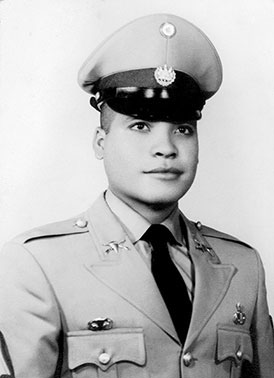

Artillery battery commander CPT José Eduardo Iraheta Castellon had been selected by the Estado Mayor (ESAF headquarters) to attend a ten-week COIN course for Latin American officers conducted by U.S. Army Caribbean (USARCARIB) in early 1962. CPT Iraheta had earlier attended a USARCARIB intelligence course in Panama. Coincidentally, CPT Carvell was one of the two SF trainees at the Special Warfare School, Fort Bragg, NC, sent to attend that same COIN course. Carvell had gone to Spanish language school before reporting for SF training. Afterwards, this USARCARIB course was substituted for the final SF field training exercise (FTX) and Carvell was assigned to D Company, 7th SFG, for a classified assignment [the advance echelon (ADVON) for 8th SFG in Panama]. After CPT Iraheta returned home, he learned that the Estado Mayor was seeking volunteers for parachute training at Fort Benning, Georgia.4