SIDEBAR

TAKEAWAYS

- The establishment of a viable guerrilla E&E overland corridor for downed UN airmen across North Korea was a failure. Hundreds of guerrillas were inserted into an inhospitable North Korea by boat and parachute, never to return. Dependency on US airlift for resupply and reinforcement contributed to their compromise and elimination by North Korean security forces. The CIA-operated C&C island bases never materialized, but EUSA guerrilla island bases on the West coast fulfilled part of the requirement;

- The MWB raids on Soviet naval mine distribution sites in North Korea were a success. Hard evidence of Russian support was provided and more than two hundred mines were destroyed. Preparatory demolition attacks against coastal infrastructure targets demonstrated the effectiveness of limited operations and provided the experience for surprise deep raids;

- Insufficient time to train the guerrillas in amphibious operations was overcome by getting UDT personnel to support rubber boat insertions behind the lines. Detailed U.S. military advisors ensured UN air and naval gunfire support as well as delivery assets;

- The success of the UDT and Ranger/Navy team demolition raids against East Coast infrastructure prompted Hans Tofte and MAJ ‘Dutch’ Kramer to organize and train a guerrilla Special Mission Group to collect intelligence and conduct maritime raids in early 1951. Their activities will be explained in the article covering JACK activities in Korea, 1951-1953.

DOWNLOAD

During the Korean War, all American military services, United Nations (UN) forces, Korean military and civilian elements, and a fledgling Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) conducted special operations. To compound the surprise of North Korea’s invasion of South Korea on 25 June 1950, neither General (GEN) Douglas A. MacArthur, his Far East Command (FEC), nor the CIA had developed strategic or tactical special warfare plans for the peninsula. Roles in behind-the-lines operations had not been defined by the military or the Agency.1 The only special warfare asset in Japan when war broke out was an Underwater Demolition Team (UDT-3) detachment. On temporary duty (TDY) from Coronado, CA, they were mapping the Japanese warships sunk off the beaches after WWII.2

General MacArthur had traditionally ‘stonewalled’ civilian agencies seeking to conduct paramilitary or intelligence operations in his theater. During World War II, he kept the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) out of the South West Pacific Area (SWPA). MacArthur did not want the CIA setting up shop in Korea, though the Agency had been running agents in Communist China and North Korea since 1947. And, the CIA shared considerable regional intelligence with FEC.3 Faced with the EUSA and depleted Republic of Korea Army (ROKA) divisions huddled in a loose defensive perimeter around Pusan by late summer in 1950, the FEC commander had reluctantly agreed to accept George E. Aurell as the CIA Special Operations (OSO) chief. The former consul of Yokohama, born and raised in Kobe, Japan, was a SWPA veteran (Nisei team chief). This endeared him to MacArthur’s ‘Bataan Gang.’ Multi-lingual Hans V. Tofte, an OSS Europe veteran, was chief of OPC (Office of Policy Coordination) in Japan.4 In this article CIA activities are untangled from the military special operations lore of the Korean War.

There are several purposes for this article. First it will correct (based on additional information), expand, and clarify “Soldier-Sailors in Korea: JACK Maritime Operations” published in 2006. Second, it will separate CIA covert and clandestine land and maritime operations (tactical and strategic) from the other special activities during the war. Third, it will show that a fluid combat situation permitted deep behind-the-lines operations in 1950-1951. And lastly, it will reveal the critical roles of military officers and sergeants detailed to the CIA.5

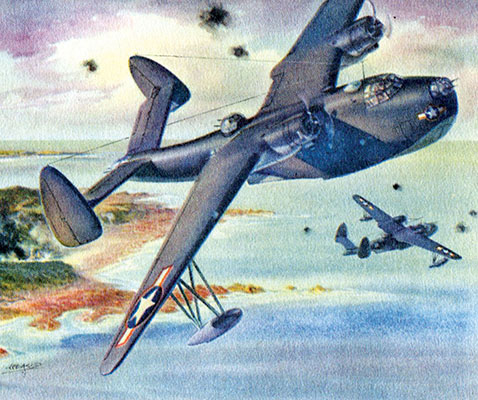

USMC and Navy UDT officers, seamen, and a CIA civilian case officer explain early paramilitary operations in Korea. The success of Navy-supported UDT/Marine demolition raids against coastal railways in August 1950 caused the Agency to emulate them. The early mission planning and preparation for paramilitary operations in Korea was done in Japan. While this article focuses on the first year of conflict, an understanding of the prewar intelligence situation in Korea is critical.

To begin, human intelligence (HUMINT) assets in South Korea were limited. With the exception of the small 971st Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) detachment in Seoul, Far East Command had no covert intelligence collection capability in Korea. Despite 971st CIC reports that North Korean divisions were integral to the Lee Hong-won Branch, 8th Chinese Route Army in Manchuria, Major General (MG) Charles A. Willoughby, the FEC G-2, ignored the implications.6

Having reluctantly allowed the CIA to establish a post in Japan in the fall of 1950, General MacArthur kept the Agency ‘under close observation’ until its second director, retired GEN Walter Bedell ‘Beetle’ Smith, came to Tokyo. General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s former chief of staff in Tunisia, Italy, and Europe and ex-ambassador to Russia visited Japan and Korea in mid-January 1951 with the blessing of a frustrated President Harry S. Truman.7 After General MacArthur had downplayed the possibility of Chinese intervention, they had attacked en masse, forcing hasty withdrawals beyond Seoul. In the process two American infantry divisions were decimated. And, contrary to U.S. national policy, GEN MacArthur had publicly advocated using nuclear weapons.

Despite that schism Smith and MacArthur reached an accord in Tokyo; FEC would not interfere with Agency activities in-theater as long as the CIA established an escape and evasion (E&E) network to recover downed UN airmen. Before coming to Japan, the Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), ‘Beetle’ Smith, had told the Army and Joint Chiefs of Staff that the Agency would provide tactical intelligence to FEC and EUSA for the duration of hostilities.8 In return, the CIA was given freedom of action in Korea. Unlike FEC, that myopically focused on the peninsula war, the Agency directed global strategic intelligence missions against the Soviet Union and Red China.9 Regardless, MG Willoughby kept close tabs on the CIA.10

The Agency had done little to define its behind-the-lines operations anywhere.11 And, the U.S. military planners had not considered the use of friendly guerrillas against Communist flanks until early 1951. Desperate after being pushed out of Seoul again, guerrilla warfare (GW) offered the means to destabilize enemy rear areas and to relieve pressure on frontline UN units.12 EUSA staff officers promoted friendly guerrillas as a low cost force multiplier while the CIA developed its paramilitary programs in Japan.13

Danish-American Hans Tofte and his deputy, Colwell E. Beers, established a large CIA training and support facility (fifty acres) on Atsugi Air Force Base, a former Japanese Navy air station forty-seven miles south of Tokyo. His OPC (covert) operations were covered as the Far East Air Forces Technical Analysis Group (FEAF/TAG). George Aurell’s OSO intelligence activities (collection and espionage), directed from Yokosuka Naval Base (near Yokohama) by his deputy, OSS China veteran William E. Duggan, were accomplished under the cover of the Department of Army Liaison Detachment (DA/LD).14 The OSO chief had an office in the Dai Ichi building (GEN MacArthur’s FEC headquarters) next to Colonel (COL) Washington M. Ives, Jr., the administrative officer for MG Willoughby. But, Aurell was not Tofte’s superior; it was a cooperative relationship.15

OPC and OSO were separate, distinct entities overseen by their respective Far Eastern Desk chiefs in Washington. While generalities about missions were shared between Agency section chiefs, as a rule they compartmented specific activities. The OSO focused on strategic intelligence collection and espionage while OPC operations were largely paramilitary.16

The CIA, charged with establishing an E&E overland corridor across North Korea for downed fliers, created a maritime ‘safety net’ with contracted native smuggling/fishing fleets on each coast extending north to the Yalu River. Tofte needed military trainers with E&E expertise. When WWII veteran USMC Major (MAJ) Vincent R. ‘Dutch’ Kramer (U.S. Naval Group China), an Agency detailee, arrived from Taiwan, Tofte grabbed him to be his paramilitary operations chief. Kramer’s first mission was to organize a multi-service planning effort to fulfill the expectations of the air leadership in Naval Forces Far East (NAVFE) and FEAF.17

The resultant E&E plan satisfied the Air Force and Navy commanders because Tofte had provided very specific guidance. An island terminus off each coast would connect a guerrilla-operated E&E ‘rat line’ spanning the peninsula just below ‘MiG Alley’ along the Chinese-North Korean border. CIA command and control (C&C) teams on these two islands were to coordinate activities and arrange support via radio. Guerrilla base camps every twenty to twenty-five miles in the E&E corridor would protect the ‘rat line.’ In lieu of having airmen carry ‘blood chits’ (promissory notes), Tofte arranged to provide small gold bars for survival kits. Fishing fleets that smuggled contraband to the north were to be contracted to patrol both coasts and periodically check offshore islands for stranded UN flyers. In return Tofte could de-brief rescued airmen to improve the E&E system.19 It was up to MAJ ‘Dutch’ Kramer to turn the plan into reality.