FULL SERIES:

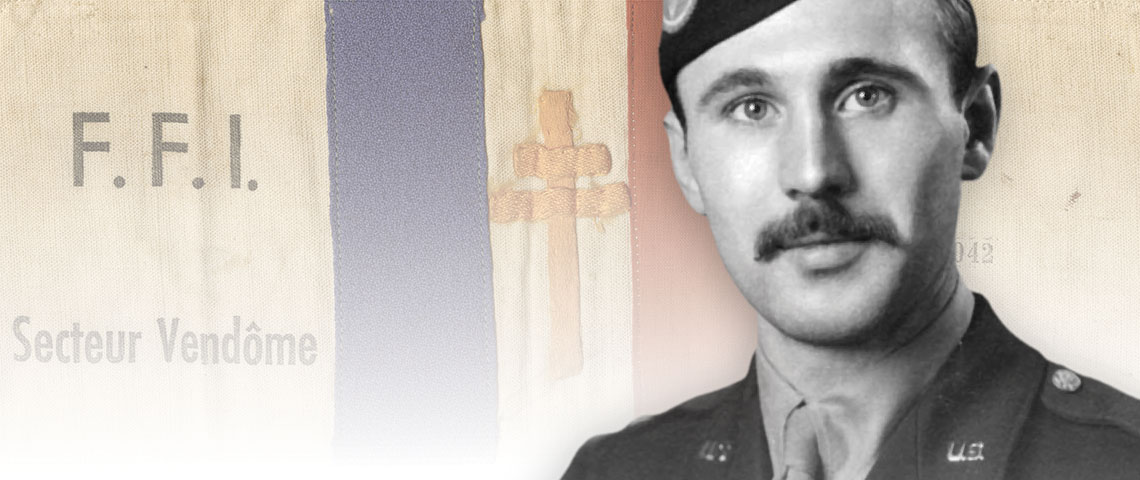

Major Bruckner

Part I: SOE France, OSS Burma and China, 10th SFG, SF Instructor, 77th SFG, Laos, and Vietnam

Part II: Pre-WWII–OSS Training 1943

SIDEBAR

DOWNLOAD

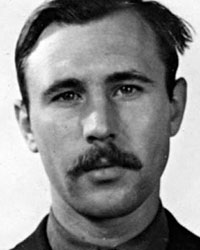

To date, the pre-World War II OSS (Office of Strategic Services) and the British SOE (Special Operations Executive) training experiences of a Special Forces pioneer, Major Herbert R. Brucker, have been presented in Part III: SOE Training & “Team HERMIT” into France.1 After his duty with SOE/OSS in France, Brucker volunteered for OSS Detachments 101 in Burma and 202 in China. He was a “plank holder” in the 10th Special Forces Group (SFG) with Colonel Aaron Bank (former OSS Jedburgh), served in the 77th SFG, taught clandestine operations in the SF Course, and went to Laos and Vietnam in the early 1960s.2

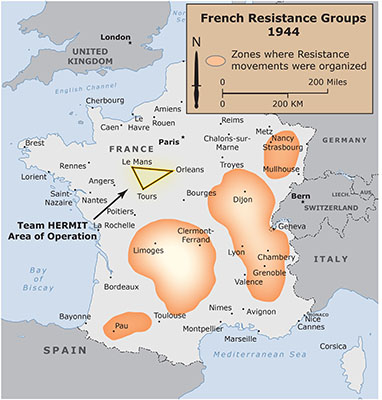

This article will feature SO (Special Operations) Team HERMIT operations in south-central France from May through September 1944, which supported the French Resistance conducting unconventional warfare missions north of the Loire River. During this assignment, Second Lieutenant Brucker, the radio telephone operator (RTO) for a three-man SO team, received the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary valor after being caught at a German roadblock. The purpose of this article is to explain what SO team members did operationally and reveal how complicated, demanding, and dangerous their assignments were before and after D-Day in France.

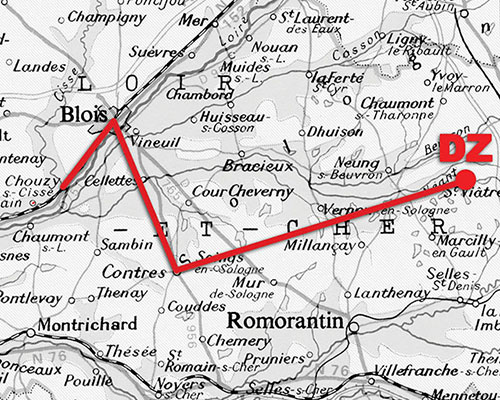

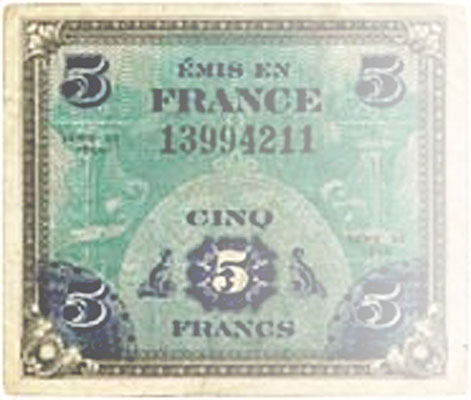

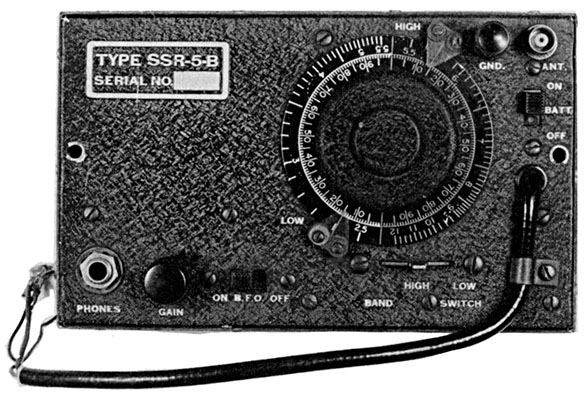

HERMIT was to replace the PROSPER team that had been “rolled up” when its female RTO, Noor Inayt Kahn (an Indian Hindu), codenamed “Madelaine,” was compromised and captured by the Gestapo in March 1944. Since Henri Fucs, a French-Jewish surgeon, had injured his leg in a bicycle accident in England, Team HERMIT was dispatched as a two-man element—2LT Brucker, codenamed “Sacha,” and his team leader, Roger B. Henquet, codenamed “Roland,” the former vice president of Schlumberger Oil in Texas. They jumped into St. Viatre, France, on 28 May 1944, accompanied by another operative, Second Lieutenant Emile Rene Counasse, the new RTO for Team VENTRILOQUIST.3 Unfortunately, all of the Team HERMIT equipment bundles and VENTRILOQUIST supplies were lost in the lakes surrounding the drop zone. Because that had never happened before, the airdropped bundles were not equipped with flotation devices. “Antoine,” the leader of SOE Team VENTRILOQUIST, was initially very hostile. But, when Henquet gave him his team’s money and new operational instructions from London, “Antoine” became friendlier and agreed to give HERMIT a radio.4 That was the most critical item for an SO team.

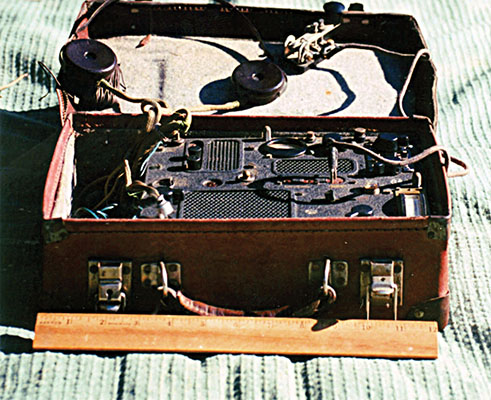

Radio confirmation within twenty-four hours that Team HERMIT had arrived safely was important, but getting to a “safehouse” that first night was critical. However, once ensconced, the two HERMIT operatives got little sleep. “Combined with our high adrenalin and nervousness, there was a perpetual parade of local people wanting to meet and welcome the American ‘liberators.’ I was wondering, ‘What the heck had I got myself into?’ It was a circus. Talk about not feeling safe,” said Brucker. “But, just after daybreak, Advent Sunday, ‘Antoine’ brought a Mark III radio and gave us the latest version of French ID documents. While he warned Lieutenant Henquet against the Communist FTP [Francs-Tireurs et Partisans] north of the Loire River, I set up my radio, dropping the antenna wire down the stairs. London ‘came in’ like it was next door. After reporting our safe arrival, I helped Counasse encode his message properly. Our next report to London would be to inform them that HERMIT was operational.”6 Then, the pretense of security became ridiculous.

Advent Sunday and the clandestine arrival of two American liberators earlier were the “talk of the town.” “It turned out that we were hiding in the mayor’s house. Mrs. Soutif intended to make the most of the opportunity. Still in our three-piece suits, our hostess insisted that we enjoy the beautiful, sunny spring day with wine and a multi-course dinner set outside in their garden gazebo. As we nervously chit-chatted outside, groups of villagers strolled by on the way to, or coming from, church curiously peeking over the fence. The meal lasted forever. It was an agent’s worse nightmare. We had to get away and find some country clothes,” recalled Brucker.7 At dusk, an escort from the local Resistance arrived.

Finding another safehouse was simpler than acquiring the peasant clothes required to help them blend into the agrarian environment—accessing the black market on Advent was risky. Only the local doctor wore a coat and tie. The average French peasant in the countryside typically owned two sets of denims (one being worn while the other was being washed and dried). His only suit and tie were worn Sundays and for funerals. Thus, a set of cheap denim work clothes (smock-like jacket and trousers) proved to be very costly for Brucker. “I didn’t care what the denims cost. I wanted out of that hot ‘monkey suit.’ I wanted to become invisible by blending in,” said the SO operative. “Thankfully, our new safehouse on the outskirts of another village was empty.”8

“The place was straight out of a Hollywood horror movie. It had an iron gate whose rusty hinges squealed loudly in protest as we entered. The yard was overgrown. The owner, carrying a flashlight, unlocked the back door with a huge old-fashioned key. As he pulled the door open, a flock of bats came rushing out. That gave us a real start,” related Brucker. “All the windows had been shuttered up. A half-inch of dust covered the cloths cloaking the furniture. After guiding us to the bedrooms upstairs, our host, promising to bring breakfast in the morning, left, locking the door behind him. I remember Henquet saying, ‘All we need to make this a set for a horror movie is a graveyard outside.’”9

And that is what they discovered the next morning (29 May 1944, Day 2). Opening a window and pushing the shutter aside, 2LT Brucker saw Henquet’s graveyard a short distance away. He then heard airplanes approaching at a low level from the rear of the house. “I stood there somewhat mesmerized as two German Messerschmitt ME-109s buzzed over the house. Fighters overhead were so common in England that I did not react until I noticed that those two planes had black crosses on their wings. They definitely weren’t ours. It hit me that we were overseas on an operation, not back home,” said Brucker. “Opening the window was not smart, especially when we noticed our footpaths through all that dust. We were screwing up like two amateurs and this was serious business.”10 However, more surprises awaited Team HERMIT on the way to its assigned area of operations (AO) north of the Loire River.

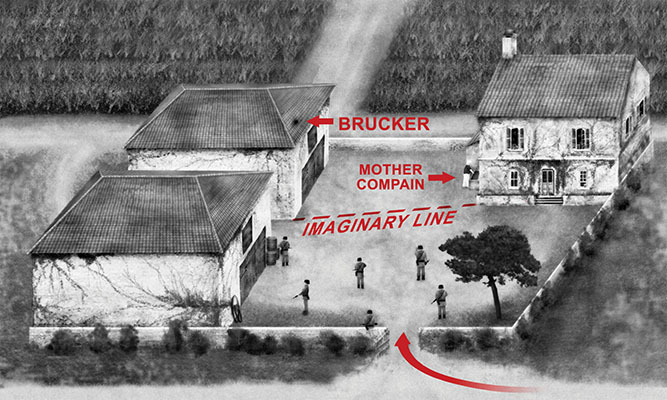

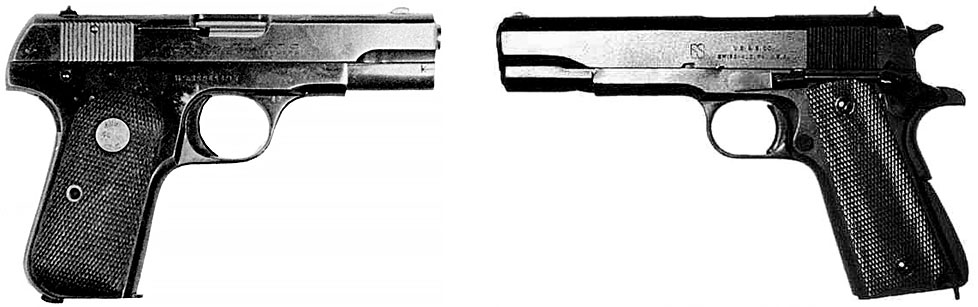

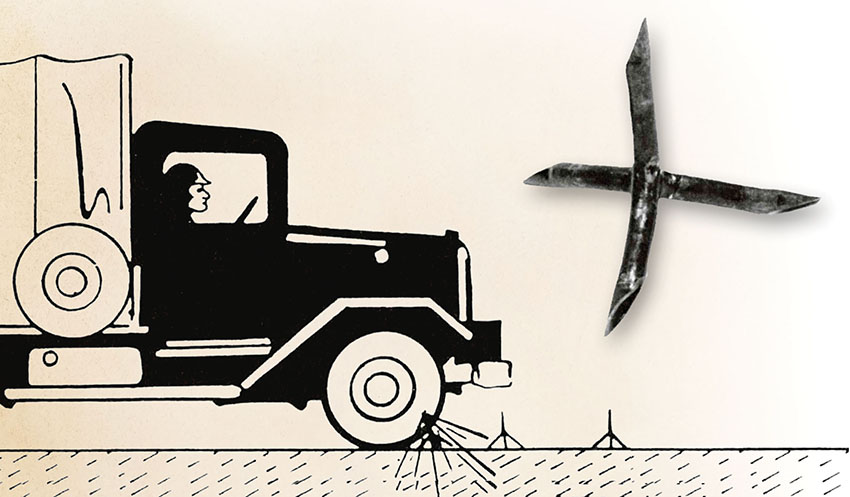

After a meal of eggs, sausage, and bread, two French Resistance members with submachineguns (SMGs) arrived to take LTs Henquet and Brucker to their AO. They drove up in an early 1930s sedan. Since gasoline was not routinely available to French civilians, the car had been converted to operate using a charcoal/wood chip boiler system—gasozhen. “Henquet and I clambered in the back with our weapons (pistols), briefcases, and the Mark III radio between us. [As noted earlier, all the bundles with the radios, SMGs, emergency rations, etc., had been lost in the lakes adjacent to the DZ.] The car’s trunk was filled with charcoal. Then, off we puttered at twenty miles per hour like we were going out for a Sunday drive. It was crazy, but we didn’t have much choice. The car was underpowered and slow, but it beat walking. Near Contres, about halfway (twenty-five kilometers from our destination), we had a flat tire, of course. Our two French escorts simply jacked up the car and proceeded to take the tire apart. I hid the radio in some bushes nearby. They had several spare inner tubes covered with patches; one did not leak. Several horse-drawn wagons carrying German troops passed by while we ‘nonchalantly’ busied ourselves with the repair. That was my first glimpse of the ‘mighty Wehrmacht.’ The tire repair took an hour and a half. Anticipating a German checkpoint on the Loire River bridge at Blois, we made plans for a worst case scenario. But luck was with us. The enemy guard posts were unmanned. I’ll never forget that trip,” said Brucker. “I hid my radio in the Blois Forest before they delivered us to our Resistance contact at a third safehouse in Chouzy, six kilometers from Blois.”11

The next challenge for Team HERMIT was transportation. Railways were out of the question for obvious reasons. Cars and trucks were not their transportation of choice. Bicycles were most commonly used by French working people. The two SO men had to blend into their agrarian environs. “A good agent must have good muscles, as our daily average bicycle mileage was between eighty and one hundred kilometers (fifty to sixty miles),” reported Henquet.12 Again the dilemma was availability; there were none to be acquired on the local black market. The alternative was to steal some from a French collaborator with German and criminal connections. Arrangements were made with a local Resistance contact to effect a “midnight requisition” on Night 3 (29 May). Then, the three burglars waited an hour after the collaborator turned off his lights before they approached a storage shed. After breaking the lock and slipping inside, the trio found only two bicycles—a woman’s and a tandem model. Both were taken and the three thieves pedaled off in the night. That accomplished, Team HERMIT was ready for operations.13