DOWNLOAD

The U.S. Army in Korea in 1950 was in many respects indistinguishable from the one that fought World War II. The divisions in Korea were organized and equipped in the same way as the Army of 1945. The post-war demobilization shrank the Army dramatically and there was little in the way of innovation and fielding of new equipment in the 1940s. When the Korean War began, huge stocks of surplus WWII equipment were reissued to the forces fighting in the Far East. With the possible exception of “Mickey Mouse” boots, the troops that landed at Inch ‘on used essentially the same equipment as their predecessors at the Battle of the Bulge. However, in one area, psychological warfare (Psywar), there was a revitalization of a virtually moribund capability that resulted in the rapid development of new systems and the establishment of a new Army training center. With the exception of a small cadre of WWII veterans at Fort Riley, Kansas, the Army had no active element to either develop the doctrine and techniques of Psywar or to test and field new equipment. The rebirth of Psywar during the Korean War had a significant and lasting impact on Army Special Operations.1

From the beginning of the war in June 1950, the Army recognized the need to counter the well-developed and pervasive Communist propaganda. The end result was the Army acquiring the capability to conduct full-spectrum Psywar targeting both friendly and enemy populations. Using all available media, the initial emphasis was on tactical Psywar featuring loudspeakers situated near the front lines and aerial-delivered leaflets directed at enemy troops. By mid-1951, the Army built a capability to conduct strategic Psywar through precisely crafted radio broadcasts into North Korea and China through stations established in Japan and South Korea. Simultaneously, the Army institutionalized Psywar capability by creating the Office of the Chief of Psychological Warfare (OCPW) in 1951 and establishing the Psychological Warfare Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina in 1952.

This issue of Veritas looks at the implementation of full spectrum Psywar as it developed in the Far East Theater and the concurrent establishment of the psychological warfare training base in the United States. It covers in detail the arrival in Japan of the 1st Radio Broadcasting & Leaflet Group (RB&L) in support of Far East Command (FECOM) and the unit’s important role in the operation of Radio Tokyo. The 3rd Reproduction Company (3rd Repro) provided the off-set printing capability for the 1st RB&L. The mission of the 3rd Repro is told by the men who served in it, which also paints a picture of the daily life of soldiers in Occupied Japan. This issue documents the establishment of the OCPW as it developed out of the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) and features a biography of Brigadier General (BG) Robert A. McClure, a prominent figure in the early history of Army Psywar who was instrumental in the rebirth of Army Special Operations during the Korean War era.

This issue divides the history of the 1st RB&L in the Korean War into three distinct phases, the arrival of the lead elements, support to the UN negotiations and the arrival and employment of the main body, corresponding to the evolving mission of the unit. Initially, the advanced echelon (ADVON) of the 1st RB&L deployed in July 1951 from the United States to Tokyo, Japan. The first mission was to support the United Nations negotiation team at Kaesong. Sending teletype messages back to Far East Command (FECOM) in Japan, the 1st RB&L personnel (predominately journalists and scriptwriters) became “sources close to General Ridgway” in the ongoing coverage of the negotiations. They helped to counter the propaganda generated by English and Australian “fellow-travelers,” pro-Communist sympathizers broadcasting English language messages from the site of the talks. Those members remaining in Japan were focused on the unit’s second priority, preparing to receive the main body of the Group when it arrived.

The two principal subordinate units in the 1st RB&L were the 3rd Repro and the 4th Mobile Radio Broadcasting Company (MRBC). The 3rd Repro personnel arrived ahead of their primary piece of equipment, the state-of-the-art Harris offset printing press. The presses, purchased on the civilian market, arrived with the last elements of the Group in September 1951. In the interim, the 3rd Repro used the less efficient Webendorfer presses and operated from their new print facility in Motosumiyoshi. The presses were dedicated to producing leaflets.

The major function of the 3rd Repro was to prepare leaflets to be airdropped or delivered by artillery. The 1st RB&L artists designed the leaflets in Tokyo and printed them at the Motosumiyoshi facility. While the 3rd Repro established its printing operations in Japan, its sister unit in the 1st RB&L, the 4th MRBC, established its radio systems in Japan and South Korea.

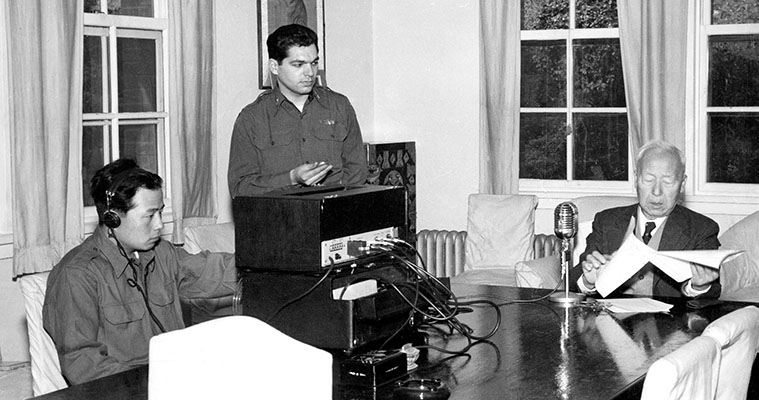

The unit established Radio Tokyo in support of FECOM. One of the first missions of the 4th MRBC was broadcasting radio messages into North Korea as early warning of the U.S. Air Force bombing campaign. This humanitarian gesture was coordinated by the officers of the company who received teletype messages of scheduled air strikes. The warnings were broadcast one hour prior to the attacks in an effort to reduce civilian casualties. The 4th MRBC continued to support Radio Tokyo while moving into the second phase of its operations which involved deploying elements of the company to South Korea.

Until the end of the war, the 1st RB&L continued to employ the full spectrum of Psywar assets in theater. The development of this capability was facilitated by the establishment of the Psywar Center at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, where the training foundation for rebuilding the Army Psywar capability was accomplished. The revitalization of Psywar was due almost entirely to the vision of one man, BG Robert A. McClure.

While the Psychological Warfare Division existed on the Army staff, it was just that, a staff element without the capability to develop the doctrine necessary to train Psywar personnel. Fortunately, in BG McClure, General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Chief of Psychological Warfare in WWII, the Army had an experienced and aggressive champion for Psywar. BG McClure campaigned for the rejuvenation of the Army’s Psywar capability, and in 1952 his tireless efforts were rewarded with the establishment of the Psywar Center at Fort Bragg, NC. BG McClure played a critical role in the establishment of the Psywar Center and School (PWS) which became the foundation for modern Army Special Operations Forces.

From the need to counter the Communist propaganda effort arose the realization that the Army needed to commit assets and training to Psywar. The establishment of the Psywar Center set the stage for the permanent incorporation of Psywar into the Army organization. Today’s Military Information Support Operations units derive their history from these beginnings.