On 20 March 2003, a U.S.-led coalition launched Operation IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF) to remove Iraqi President Saddam Hussein from power. This was the second major military operation of the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), following Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), the successful unconventional warfare campaign in Afghanistan. However, unlike OEF, Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) represented a small part of a much larger coalition during OIF. Nevertheless, it contributed significantly to the rapid victory over the Iraqi armed forces, as well as to the lengthy counterinsurgency mission that followed.

Background — The “Axis of Evil”

With OEF still underway in Afghanistan, the Philippines, and elsewhere, President George W. Bush and his administration began sounding the alarm about the threat posed by Iraq, Iran, and North Korea. In his State of the Union Address on 29 January 2002, President Bush said: “States like these, and their terrorist allies, constitute an Axis of Evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world. By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes pose a grave and growing danger. They could provide these arms to terrorists, giving them the means to match their hatred.” He concluded, “the price of indifference would be catastrophic.”1

In a 12 September 2002, address to the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, President Bush presented his case against Saddam Hussein, saying, “If Iraq’s regime defies us again, the world must move deliberately, decisively to hold Iraq to account.”2 The following month, on 16 October, the U.S. Congress authorized the use of military force against Iraq.3 Then, on 8 November, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1441 ordering Hussein to allow international inspectors to dismantle his weapons program or “face serious consequences.”4 Hussein refused, just as he had done with previous UN mandates.

A week later, the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) authorized the Joint Psychological Operations (PSYOP) Task Force (JPOTF) to commence messaging intended to shape the environment for potential U.S. offensive operations against Hussein’s Baathist regime, if needed. Throughout early 2003, U.S. conventional and special operations units and their allies maneuvered into position, preparing for an invasion that seemed increasingly inevitable.

Operation IRAQI FREEDOM Begins

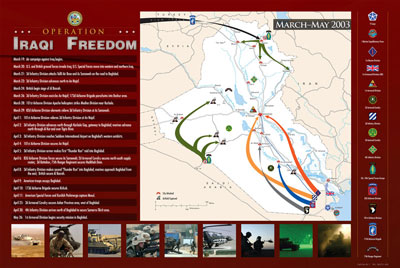

The invasion of Iraq began during the predawn hours of 20 March 2003. U.S. Army Special Forces (SF) Operational Detachments-Alpha (ODAs) from 5th SF Group (SFG) infiltrated into Iraq in advance of the main assault to conduct reconnaissance.5 More ODAs followed, seizing the abandoned Iraqi airfield at Wadi al Khirr.6 5th SFG and its supported elements formed the core of Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force (CJSOTF) — West. In Romania, Task Force Viking (10th SFG augmented by a battalion from 3rd SFG) prepared to join the war a few days later, their infiltration having been complicated by Turkey’s refusal to provide a staging base.7 Once in northern Iraq, they helped to open a second front, in conjunction with their Kurdish allies.

On 26 March, 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (SOAR) aircraft inserted 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, onto a suspected chemical and biological weapons development facility.8 The 160th then successfully evacuated the Rangers, after a sustained firefight. Then, on 31 March, 3rd Ranger Battalion seized the Haditha Dam complex northwest of Baghdad.9 Attack helicopters from the 160th SOAR provided aerial reconnaissance and fire support.10 Once the dam was secure, 96th Civil Affairs (CA) Battalion soldiers arrived to help get it back into operation.11

In Operation VIKING HAMMER, TF Viking reinforced Kurdish Peshmerga forces arrayed against Iraqi Army positions along the “Green Line” in northern Iraq. Before advancing on Iraqis to its front, the TF had to deal with Ansar Al-Islam terrorists operating to their rear.12 By 11 April, TF Viking and its Kurdish allies had captured Mosul, the third most populous city in Iraq.13

During the invasion, Tactical PSYOP Teams from 9th PSYOP Battalion (POB) and various Army Reserve PSYOP companies advanced into Iraq alongside their supported units, both SOF and conventional.14 Soldiers from 8th POB manned the JPOTF and later supplied a Military Information Support Team in Baghdad. The 3rd POB employed multiple Special Operations Media System — Broadcast (SOMS-B) units to disseminate PSYOP radio and television messages. It also printed large quantities of leaflets and other physical products. The Pennsylvania Air National Guard’s 193rd Special Operations Wing also broadcasted PSYOP messages from EC-130 Commando Solo aircraft.15

In northern Iraq, CJSOTF-North (TF Viking) turned to Bravo Forward Support Company (FSC), 528th Support Battalion, for logistical support and Company B, 112th Signal Battalion, for secure communications.16 In southern Iraq, Alpha FSC, 528th Support Battalion, and Company C, 112th Signal Battalion, supported the 5th SFG-centric CJSOTF-West. Meanwhile, the Special Operations Support Command, the overall ARSOF Support headquarters, deployed its command team to Iraq to take the helm of Logistics Task Force — West.17

A particularly well-publicized ARSOF success during this period occurred on 1 April 2003, when Private First Class. Jessica Lynch was rescued from Iraqi captivity. Lynch had been taken captive after Iraqi forces ambushed her unit, the 507th Maintenance Company, in Nasiriya, Iraq, on 23 March.

Baghdad fell to coalition forces on 9 April and Saddam Hussein went into hiding. Combat operations were over by May, but a large contingent of ARSOF remained in Iraq to help facilitate what most hoped would be a quick and peaceful transition.18 In May, the two CJSOTFs (North and West) were consolidated into the CJSOTF — Arabian Peninsula (CJSOTF-AP), which assumed operational control of the majority of SOF in Iraq. CA and PSYOP units supported the CJSOTF-AP, Joint SOF, and conventional elements, as required. Other ARSOF units operated as part of Joint Special Operations Task Forces, hunting down Saddam Hussein, his sons, and former members of his regime.

The Insurgency Mounts

Following the collapse of the Baathist government, and the subsequent disbanding of the Iraqi Army, former regime elements and other sectarian groups launched a tenacious insurgency against coalition forces. Foreign fighters, answering the call to jihad, flocked to Iraq to join the fighting in the months and years that followed. This insurgency tested the coalition’s resolve and severely strained Iraq’s newly established governing institutions and security forces. The insurgency expanded in 2004, despite the capture of Saddam Hussein the previous December, which some had hoped would remove their motivation for fighting.19

The ratification of a new constitution and multiple rounds of democratic elections in 2005 did not have the anticipated effect on security. By 2006, the insurgency had intensified to the point that Iraq was on the verge of all-out civil war along ethno-sectarian fault lines. Even the death of Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the notoriously brutal leader of Al-Qaeda in Iraq, on 7 June 2006, did not fundamentally alter the trajectory of Iraq.20 The situation was growing dire.

Time is Running Out

That December, the bipartisan Iraq Study Group (ISG) provided a grim assessment: “Stability in Iraq remains elusive, and the situation is deteriorating. The Iraqi government cannot now govern, sustain, and defend itself without the support of the United States. Iraqis have not been convinced that they must take responsibility for their own future…[and]…[t]he ability of the United States to shape outcomes is diminishing. Time is running out.”21

A month later, on 10 January 2007, U.S. President George W. Bush announced that he was sending 30,000 additional troops to Iraq to stabilize the situation through an aggressive counterinsurgency strategy.22 The move was almost immediately termed “The Surge.” Though controversial, this change in strategy proved successful. Violence decreased across Iraq, buying time for the Government of Iraq to prove itself capable of governing and taking the lead on its own security.

During the Surge period (2007-2008), ARSOF intensified efforts to disrupt and destroy terrorist and insurgent networks, both unilaterally and in conjunction with Iraqi partners.23 The CJSOTF-AP operated alongside the Iraqi Special Operations Forces (ISOF) units that it had helped create, which were now operationally controlled by the new, Iraqi-led Counter Terrorism Service.24 PSYOP and CA promoted good governance, democracy, economic opportunity, and Iraqi unity, while highlighting the progress made by Iraq’s security forces. By early 2009, the situation in Iraq was as stable and promising as at any point since the fall of Baghdad six years earlier. Upon taking office that January, newly elected President Barack H. Obama declared his intention to follow through on his campaign promise to withdraw U.S. forces from Iraq.25

By the conclusion of OIF on 31 August 2010, thousands of ARSOF soldiers had served in Iraq and 96 had made the ultimate sacrifice.26 None were lost in the follow-on mission, Operation NEW DAWN, which lasted until 31 December 2011. Concurrent with the Iraq drawdown, USCENTCOM shifted its focus back to Afghanistan, where the former Taliban regime and other violent extremists threatened to reverse the progress made since the start of OEF. ARSOF remained engaged there for the next decade.

The strain of continuous operations, most intense at the height of OIF, prompted significant enhancements to the ARSOF force structure. By the time ARSOF returned to Iraq in 2014, as part of the successful counter-Islamic State mission (Operation INHERENT RESOLVE), each active-duty SFG had a fourth line battalion and a group support battalion. New PSYOP, CA, and Ranger units had also been activated, along with new headquarters for Special Operations Aviation and ARSOF Support. ARSOF was also more capable and combat-tested, due to its lengthy OIF experience between 2003-2010. That experience continues to benefit ARSOF today, with OIF veterans occupying many key leadership positions within the U.S. Army Special Operations Command.