FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

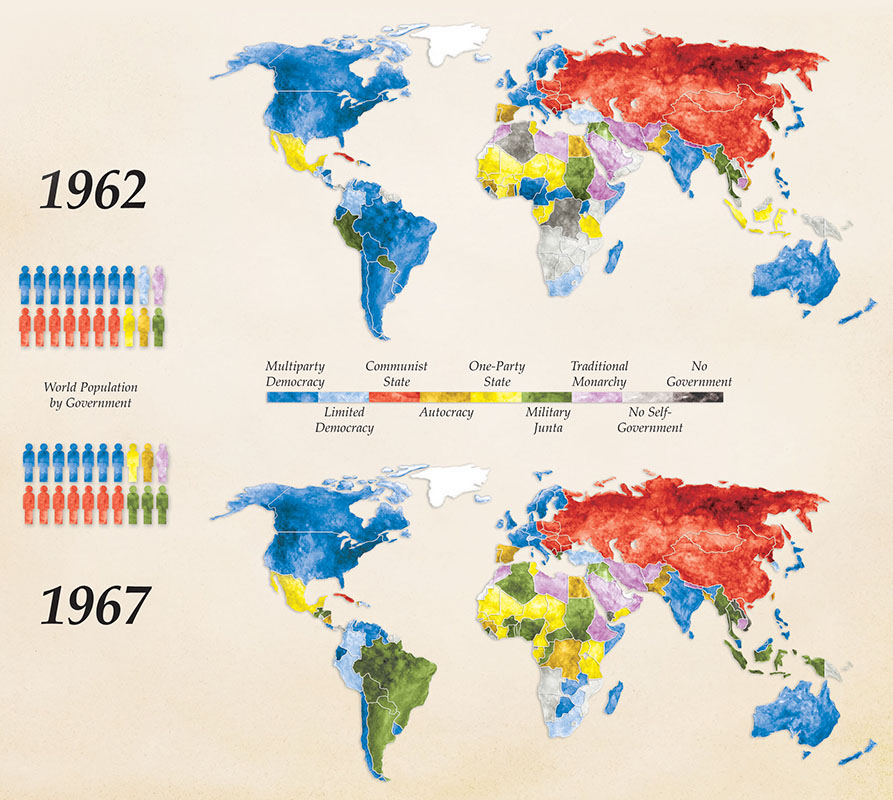

The decade of the 1960s witnessed profound change in the established world order. The post-WWII global configuration was essentially bi-polar, with the United States-led West aligned against the Soviet-dominated East. In the 1960s, this split along ideological and economic lines divided the world into five centers of power: the Soviet Union and its satellites; Communist China and Southeast Asia; Europe and the United States; Africa; and Latin America. This article will look briefly at each of these regions and the general United States foreign policy strategy for each. The emphasis will be on Latin America, in particular Bolivia, and events such as Cuban-instigated insurgencies, affecting U.S. engagement in the southern hemisphere. In Latin America, Cuban-sponsored revolutionary fervor was a major factor in determining the U.S. strategy.

The Allied powers determined at the end of World War II the Security Council’s permanent membership in the newly formed United Nations (Chiang K’ai Shek’s Nationalist China, not Communist China, held a permanent seat). The power blocs of the Fifties began to erode in the Sixties. It was the Soviet Union that faced off against the West in the Cold War, and instigated such provocations as the erection of the Berlin Wall.1