FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

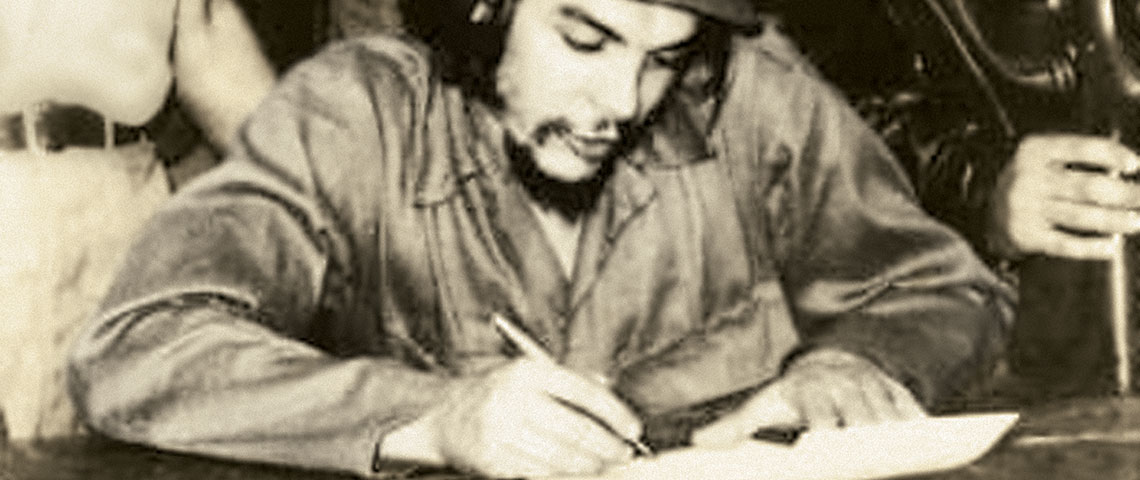

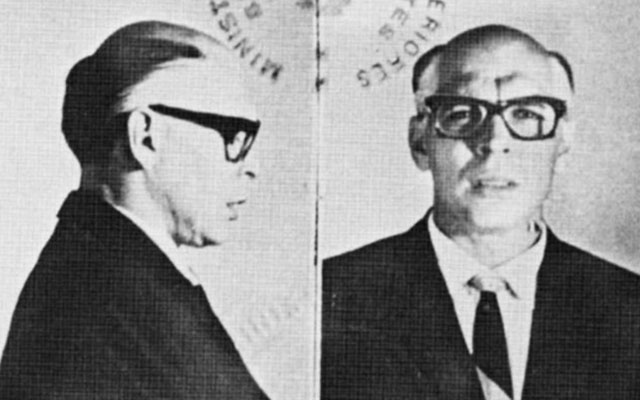

On 7 November 1966, Ernesto “Che” Guevara began his diary with the entry, “Today a new stage begins.”1 Disguised as a bald man with large glasses, Che using the name Adolfo Mena González, an Organization of American States researcher, entered Bolivia to launch a revolution.2 He had dreamed of bringing his version of revolution to the heartland of South America while he was fighting in the Sierra Maestras of Cuba a decade earlier:

I’ve got a plan. If some day I have to carry the revolution to the continent [South America], I will set myself up in the selva [forest or jungle] at the frontier between Bolivia and Brazil. I know the spot pretty well because I was there as a doctor. From there it is possible to put pressure on three or four countries and, by taking advantage of the frontiers and the forests you can work things so as never to be caught.3

Cuba became the advocate of “wars of national liberation” when 400 delegates of the newly formed Organization of Solidarity of Asian, African, and Latin American Peoples (called the Tricontinental) met in Havana in January 1966. A central topic of discussion was Che Guevara’s revolutionary concept. Fidel Castro publicly committed himself to this new international revolutionary movement and subsequently created the Latin American Solidarity Organization (OLAS) to control and coordinate revolutionary activities in the Western Hemisphere, with Cuba in a leadership role.4

Within this new framework, Che Guevara was given a major role in coordinating a revolutionary act in South America. Following his failure in the Congo, Che needed time to recover. While abroad he had become an international Communist “boogey man,” mysteriously disappearing and reappearing. U.S. and allied intelligence agencies searched for him in the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Colombia.

Che firmly believed that the only way to break free of imperialist oppression was to involve the United States. Multiple simultaneous uprisings in Latin America would lead to the final defeat of the ultimate enemy, the United States. “It is the road of Vietnam; it is the road that should be followed by the people; it is the road that will be followed in Our America … The Cuba Revolution will today have the job of … creating a Second or Third Vietnam of the world.”5 His dilemma was where to start.

Che considered several countries, particularly Peru and his native Argentina. However, Bolivia seemed to be the best candidate, based on Cuban intelligence reports and his personal experiences. As a young man traveling through Latin America, Che stopped in Bolivia in 1953, the year after the Bolivian Revolution and was impressed by the move toward radical social reforms. Since then he became convinced that politicians, generals, and the United States had corrupted the Bolivian Revolution. However, Che’s intelligence regarding Bolivian social conditions in 1967 was highly inaccurate.

Two Bolivian communists, Roberto “Coco” Peredo Liegue and Guido “Inti” Peredo Liegue, were his primary sources of misperception. They reinforced his earlier analysis during visits to Cuba in 1962 and again in 1965.6 They, like many other Bolivian communists, related stories of widespread dissent with the regime of President Rene Barrientos. They ignored the fact that Barrientos had won the election with more than 60% of the vote.7 Guevara accepted the popular consensus that the Bolivian military was one of the most poorly organized in Latin America.8 All of these elements convinced Che that Bolivia was the best candidate for a foco.

Che’s revolution would begin in the corazón, the “heart” of South America – Bolivia.9 The Cuban revolutionary experience in the Sierra Maestras would be the template to spread insurgency throughout the South American continent. First, the foco would be established with Cuban leadership and military support. Second, after organizing his foco, building base camps and a logistical cache, and training guerrillas would begin. Then small groups of guerrillas, using “hit and run” tactics, would harass the Bolivian Army and police. As the guerrillas became more effective, the Bolivian army had to disperse to protect towns and infrastructure. This strategy made the Army even more vulnerable to attacks. As this Cuban-led revolutionary vanguard grew in strength it would gain more support from the campesinos, farmers, and miners. Victories would demonstrate their ability to defeat the army and improve their legitimacy.

Eventually, the foco would gain enough strength to strike three of Bolivia’s major cities: Cochabamba, Santa Cruz, and Sucre. Once the guerrillas isolated or controlled these cities, they effectively split the country. Part of the strategy would be to sever the railroad line to Argentina and the major oil pipeline between Santa Cruz and Camiri, further isolating the country.10

As the guerrilla movement gained strength and momentum, Che was convinced that the United States would send military advisors as they did in the Republic of Vietnam. Conventional units would follow the advisors. Che hoped to increase U.S. military obligations in Latin America. As the second and third ”Vietnam” erupted, the American army would rapidly exhaust itself in a vain attempt to support counterinsurgency efforts.11 From Inti Peredo’s perspective: “As they become incapable of defeating us, the U.S. Marines will intervene, and imperialism will unleash all its deadly power. Then our struggle will become identical with the one being waged by the Vietnamese people.”12 This was only a beginning to foster regional insurgencies.

Once the Bolivian guerrilla vanguard was firmly established, it would train and support other revolutionary movements (focos) in Peru, Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay. The Peruvian foco was scheduled for the end of 1967. Eventually Che predicted that the Bolivian foco would defeat the government and, like Cuba, establish a revolutionary government. The focos still needed support, and Bolivia would become a sanctuary for the various groups. Bolivia would be the first to fall, triggering subsequent collapses to create a South American “domino effect.”

There were several elements in the organization of the Bolivian foco. The nucleus was the Cuban revolutionary fighters. The majority of the foco would be locals, drawn from the ranks of the Bolivian Communist Party (BCP). The combined element would be called the Ejército de Liberación Nacional de Bolivia (ELNB, or National Liberation Army of Bolivia). The ELNB had to plan and build a large support network. Cuba provided the monetary and weapons support for the ELNB. Behind the scenes was a network of agents collecting intelligence and providing logistics assistance, some of whom had been in place for years. The majority of the clandestine support apparatus was built around Cuban agents coordinating with the Bolivian Communist Party in La Paz. However, there were two key foreign players, Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider and Régis Debray who played significant roles as special agents for the Bolivian foco.

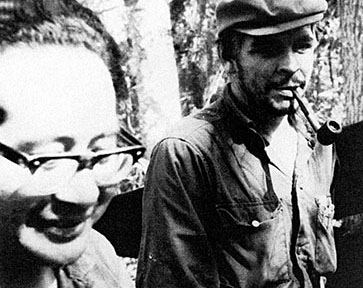

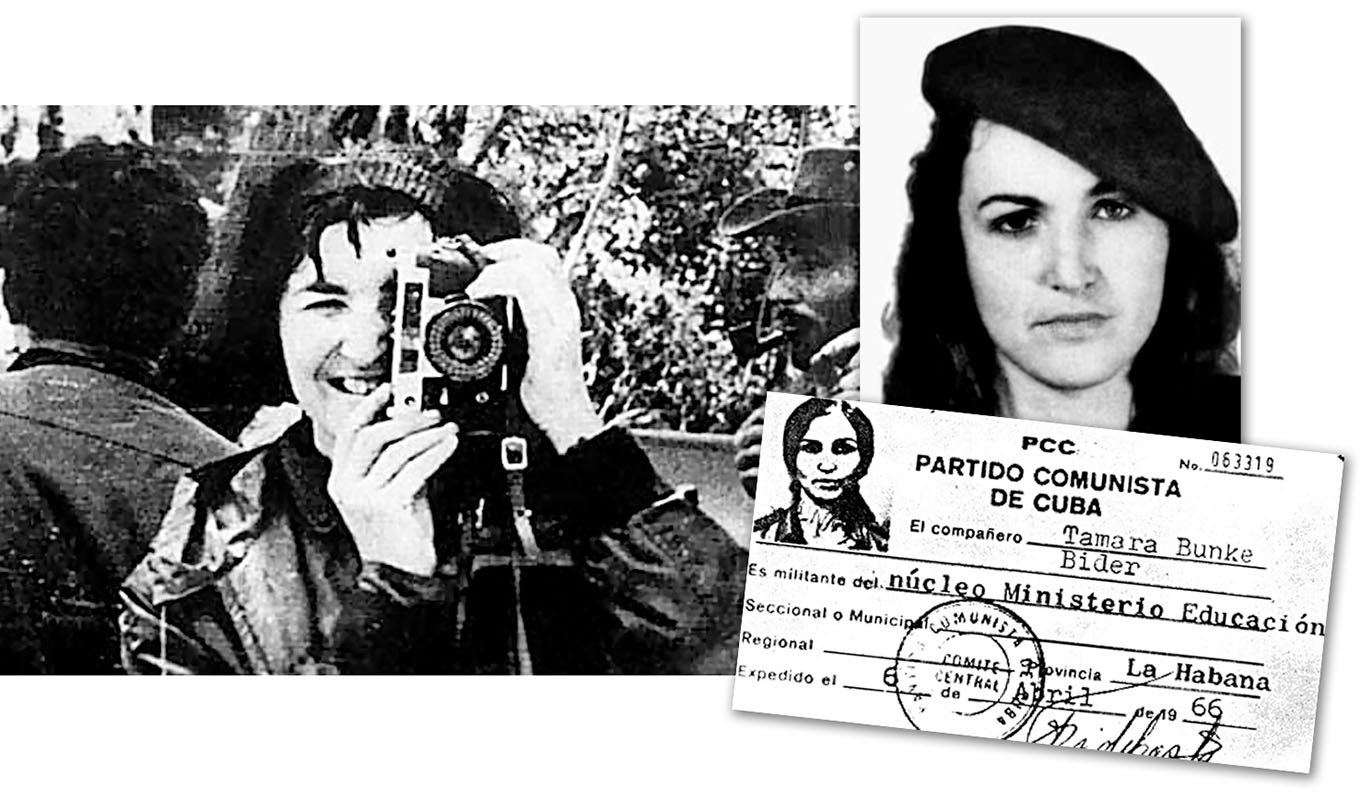

A young woman of dual Argentine-East German nationality, Haydée Tamara Bunke Bider was best known by her code-name, “Tania.” After meeting Che Guevara in East Germany in 1960, she became enthralled with his revolutionary ideas. Tania subsequently traveled to Cuba where she became active in the Cuban revolutionary movement and was recruited and trained as an agent for the Bolivia mission.13 Tania went to Bolivia in 1964 under the alias Laura Gutiérrez Bauer to establish contacts among the Bolivian upper class. In her cover as a researcher of indigenous folk music and as a German tutor for wealthy children, she began collecting strategic and tactical information.14 Through her network of contacts and Communist “fellow travelers” Tania obtained Bolivian press credentials for Che Guevara, Régis Debray, and Ciro Roberto Bustos (a Cuban agent from Argentina).15 In La Paz she hosted a radio advice program for the lovelorn and used it to send coded messages to Cuban intelligence. Tania was a triple agent who also worked for the Soviet KGB and the East German secret police, the “Stasi.”16 The importance of her role in the Bolivian foco has become almost as mythologized as that of Che Guevara. The second “agent provocateur” was a French intellectual.

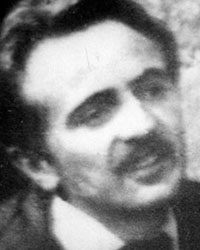

Régis Debray was a Marxist theorist and “wannabe” revolutionary in his mid twenties. The Debray family was wealthy and well connected and enjoyed a high position in French society. His father was a prominent lawyer and his mother served on the Paris city council. He had obtained a position as a professor of philosophy at the University of Havana.17 While he was there he wrote, Revolution Within a Revolution, chronicling the Cuban Revolution as the harbinger of a new revolutionary model for Latin America and the world.18 Cuban intelligence sent him to Bolivia to write a geopolitical analysis and gather intelligence.

Debray traveled to Bolivia in September 1966 posing as a journalist and professor “whose mission is to make a geopolitical study of the chosen zone in the Beni.”19 His travels did not go unnoticed “he [Debray] had been sighted moving around the Bolivian countryside—in Cochabamba, in the Chapare and in the Alto Beni—all regions that had been under discussion by the Cubans as possible guerrilla sites.”20 He collected maps and answered Che’s questions through intermediaries in Cuba.21 Simultaneously, other agents supporting the effort made arrangements for the foco.22

Following the template for the Cuban Revolution, agents purchased a ranch/farm in Bolivia to serve as a foco base. In June 1966 the Peredo brothers bought a 3,000-acre farm for 30,000 Bolivian pesos (about $2,500) near Ñancahuazú in the rugged southeastern region of Bolivia. It was dubbed the casa calamina (the “zinc house” or “tin house” for its shiny metal roof). Located fifty miles north of Camiri, the Ñancahuazú farm sat in a very rough environment in a sparsely populated area.23

Recruitment of Bolivians for the foco began in the summer of 1966. Mario Monje Molina, head of the Bolivian Communist Party, promised twenty men from his organization. Moisés Guevara Rodríguez, the Maoist mine labor leader, was another source of manpower.24 While the Bolivians would form the bulk of the new insurgency, Che planned to use Cuban veterans to train and lead the local recruits until they could assume responsibility for liberating their country.25 Recruiting was a constant problem for the Cuban-led organization.