FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

The Special Forces medic is the best-trained combat emergency medical practicioner in the American military. It takes two years of schooling and practical experience to become fully qualified, and annual re-certifications are mandatory. These soldiers have the skills of physicians’ assistants and routinely perform minor surgery in combat and remote areas. They are the prime enablers and force multipliers who “win the hearts and minds” of the populace as the SF ODA (Operational Detachment Alpha) performs its missions. They are especially important during foreign internal defense (FID) assignments with counterinsurgency (COIN) training. The two medics on the mobile training team (MTT) mission to Bolivia in 1967 fulfilled their role with distinction.

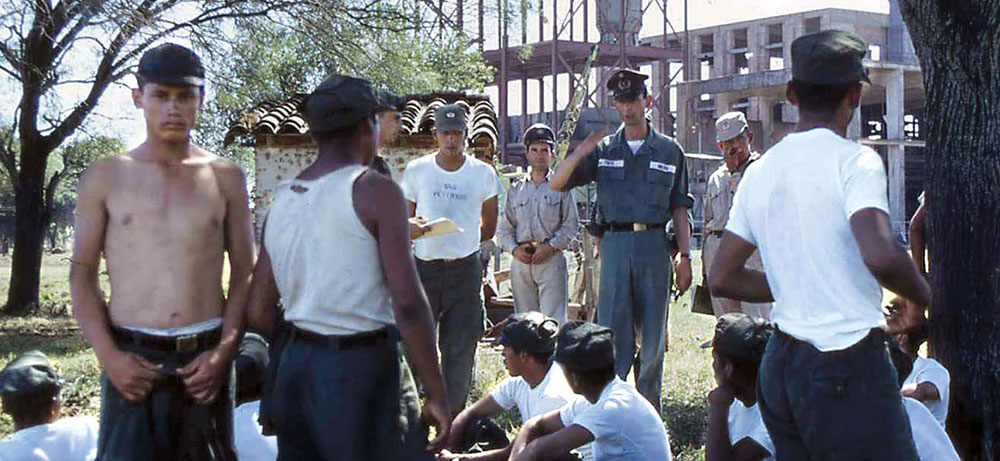

The work for the two Special Forces medics on MTT-BL 404-67X began with the arrival of the Bolivian conscripts in the early days of May 1967. The smell and accumulating filth around the warehouse where the soldiers were billeted prompted immediate action. The peasant soldiers had to be taught field sanitation immediately and the critical necessity for it became a top priority enforced by the Bolivian junior officers and sergeants. If not, disease would threaten the team’s ability to organize, field, and train a Ranger force. Classes in health, field sanitation, and personal hygiene were immediately given. Construction of several latrines 50-100 meters away from sleeping areas followed.

“It was hard to impress upon the Bolivian troops that field sanitation was important. They simply did not know any better. The majority were indios from the hinterlands whose toilet since birth had been anywhere outdoors. Water was for drinking and cooking. Bathing was optional based on available water sources. The slit trench latrine ‘model’ that we built and demonstrated how to use properly became almost a shrine. They never used it, and even those they constructed were rarely used,” said SSG James Hapka, a team medic.1 “The conscripts continued to head for the bushes. We finally convinced them to relieve themselves at least twenty meters behind their billets. Because toilet paper was foreign to most of them, there weren’t any ‘warning flags.’ You really had to keep your eyes open,” said SFC Dan Chapa. “Living with them was not an option.”2

The Special Forces maintained a separate camp with their own latrine and washing area. If they became sick their mission would be compromised. “SFC [Ethyl W.] Duffield and I dug most of our latrines. When you didn’t follow MSG [Oliverio] Gomez’s instructions exactly, the team sergeant used ‘hole digging’ to enforce discipline. He’d be up waiting for ‘Duff’ and me when we came back late from a ration run to Santa Cruz. While we were digging at night, he’d inspect our progress with his Coleman lantern. If it wasn’t shoulder high yet, he’d say, ‘Keep digging,’ and walk off,” chuckled SFC Chapa. “It was a way to keep us in line, and, because it was imposed at night, the Bolivians never knew. It kept the guys on the team laughing.”3 One other medical responsibility associated with sanitation was inspection of the Bolivian “mess.”

“It was actually an outdoor fireplace where local women occasionally cooked. Each morning the soldiers were given a piece of bread and a cup of sweet black coffee. Lunch in the field was another piece of bread that was carried in a pocket. Dinner was served from the half of a 55-gallon drum in which a “stew” of questionable ingredients simmered,” said SSG Peterson. “After MAJ Shelton tasted the concoction, we were told not to eat there.”4 “One day, out of curiosity, I asked the ‘cook’ what was in the caldron,” recalled SFC Chapa. “He gave me a dirty look and said, ‘I’m doing what I’m told.’ I responded, ‘But, you’re the cook.’ He replied, ‘I’m not really a cook. I’m just doing a job.’ I decided that there was no reason to pursue it.”5 After their collective experiences at the Bolivian “mess,” SSGs Peterson and Hapka concentrated on practicing medicine since only a few conscripts had ever been treated by a doctor.

Assessing the general health of the Bolivian soldiers by conducting rudimentary physical examinations familiarized the SF medics with several common health problems. “Most of the conscripts were illiterate, so reading an eye chart would have been futile. Dental hygiene was atrocious; care was nonexistent. Though very hardened by a tough rural life, they had a lot of skin diseases and infections, most attributable to poor personal hygiene. Since these soldiers had only grown up with a single shirt, a pair of trousers, some sandals, and a poncho, it seemed quite normal to just have one uniform,” related SSG Hapka. “That did not promote good hygiene.”6

“The training area where we did tactical field exercises had a lot of bull thorn trees that the soldiers used for cover and concealment. Those thorns were about an inch and half long and caused nasty scratches. Personal hygiene was so poor that they became infected very quickly. To make matters worse, the bull thorn trees had a symbiotic relationship with red ants. The branches being pushed aside by the first man usually triggered red ant ambushes on all those following the same route,” remembered SSG Peterson. “However, the worst infections were caused by flies or boring insects (venchugas) that attacked the raw gashes. They deposited eggs inside creating boils. These had to lanced, scrubbed out with stiff, soapy brushes, antiseptic applied, and then penicillin given to the hapless victims. Sometimes, this had to be repeated several times.”7

“Our best medic was one of these victims. His face looked like someone had thrown acid on him. It was something straight out of a horror movie. We loaded him up with penicillin and twice a day scrubbed his face clean for almost two weeks before he started healing up properly. It turned out that he was really a handsome guy. We decided to use him in the dispensary as the senior Bolivian medic. He became a real asset,” said SSG Peterson. “Hygiene precautions were taken by the Americans, but the place was full of ‘biting critters.’”8

“MSG Gomez warned us about the venchugas, so we tucked the mosquito nets under our air mattresses,” said SFC Chapa.9 Since the SF soldiers spent most of their time training Bolivian troops in the field, they encountered a variety of venomous scorpions and snakes on the ground and flying insects, spiders, and tree vipers in the wooded areas. Only one American SF soldier, SFC Chapa, suffered a near fatal injury in Bolivia.10

“C Company was getting ready to conduct a night attack. I remember walking under a tree when something hit my forehead. The next thing that I felt was a hot tingling spreading down my arms and legs and general weakness. I was having a hard time standing up,” recalled SFC Chapa.11

“MAJ Shelton got Chapa into the carryall provided by the MILGP and took him back to camp. By then, Chapa was semi-conscious when we manhandled him into the aid station. Jim Hapka and I suspected a snake bite because tree vipers were common. We cut off his clothes and examined him all over, but we couldn’t find fang marks anywhere. He was mumbling that his skin was on fire and tingling and that he felt very weak. All that we could see abnormal was a large lump on his forehead. Because Chapa’s arms and legs were swelling, Jim began treating him for anaphylactic shock, injecting cortisone between his fingers and toes,” said Peterson.12

“Since the nearest doctor was in Santa Cruz, almost two hours away, Hapka radioed Fort Gulick to call in the Group Surgeon for an emergency consult. We took shifts applying wet, cool compresses while we waited for the callback. When the surgeon in Panama could suggest no better treatment, we continued with compresses and cortisone shots. The next morning Chapa was no better, but no worse either,” continued Peterson.13

“By then word of his condition had spread among the villagers and a local healer (bruja) recommended applying a piece of raw meat to the lump on his forehead to draw out the poison. Since he was unconscious, we didn’t think that would hurt anything. So, we bandaged a slab of beef onto his forehead. Thirty-six hours later, when Chapa came to, we warned him not to touch his head or look in the mirror. When he dozed off, I removed the meat slab from his head. We didn’t want Chapa to think that the SF medics had used voodoo medicine to cure him. That was our little secret,” said SSG Peterson, “but it was pretty scary there for awhile.”14 “I was checked out by CPT Quiñones, the group surgeon, when he visited La Esperanza in November and when we returned to Fort Gulick in December,” said SFC Chapa. “I had no after effects, but the guys tried to play tricks on me saying that there was wasp behind my head.”15

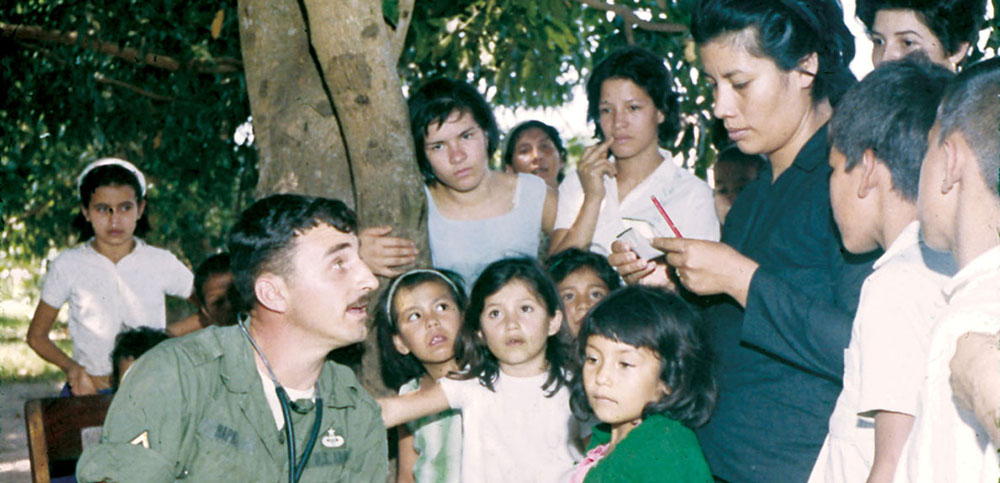

In addition to treating their own and the Bolivian soldiers, the two medics had handled forty night emergency medical calls in the community by mid-May. They started sick call for the community every Saturday morning beginning on 15 May. Night emergency visits continued. By the end of December 1967, the two had responded to 124 night calls for medical assistance. They treated 410 men, 589 women, and 1,375 children in La Esperanza alone.16 Hapka and Peterson were expected to train the field medics for the battalion.

“The medic training, while oriented around U.S. Army basic medic [today’s 68W MOS (military occupational specialty)] skills, emphasized treatment for gunshot and explosive injuries and broken bones normally associated with them. They needed to have emergency medical skills to perform immediate first aid. Today, they’re called ‘Combat Lifesaver’ skills. We taught shock symptoms, wound cleansing, proper bandaging, when, how, and where to apply a tourniquet, starting IVs (intravenous fluids), splinting broken bones, and sucking chest wound treatment. The medics were shown how to make field expedient stretchers, splints, and bandages from clothing,” said SSG Hapka. “Pete (SSG Jerald Peterson) and I built small medical aid bags for each of the field medics and resupplied as necessary. Emergency medical evacuation was a truck to the civilian hospital in Santa Cruz.”17 Along with their medical training Hapka and Peterson presented weapons classes.

“SSG Hapka and I taught the hand grenade to the battalion en masse. Throwing is a part of many American sports, but it was not a natural skill for most Bolivian peasants. We showed them first how to throw rocks accurately. That skill mastered, we started using practice hand grenades. When we took them to the range, they enjoyed watching the explosions so much that we had to constantly remind them to drop down into the prone after tossing the grenade to avoid fragments. It took a few cuts and nicks before they got the message. Even though we alternated shouting the commands and demonstrations, we were both hoarse afterwards. All we had was a small, conical megaphone. The altiplano conscripts spoke Quechua and Aymara primarily, but understood some rudimentary Spanish. While classes often evolved into ‘monkey see, monkey do,’ learning, the soldiers were always enthusiastic and eager to learn,” said SSG Peterson.18 “During the bayonet fighting, Bolivian officers were interspersed in the formation because they used weapons with unsheathed bayonets,” said SFC Chapa.19 In addition to the compass, map reading, hand grenade, bayonet fighting, and combat medic classes, medical emergencies, sick call, and medical coverage on the ranges, the SF medics dealt with training accidents.

Surprisingly, there were only three fatal accidents during the six month mission. No Americans were injured in these. The first happened on 28 July after a lieutenant ordered a soldier to clean his pistol without clearing it beforehand. The accidental discharge occurred in the crowded troop billets area. Fortunately, no one else was hurt. The Bolivian soldier died enroute to Santa Cruz.20 The most serious training accident was on Sunday, 11 August.

“This incident involved the smooth bore French 82 mm mortars. A Bolivian sergeant (sub-official), on his own initiative, decided to take his squad out for additional training one Sunday afternoon. No one in the Bolivian chain of command nor any of the Americans were notified. How he got the ammunition was unknown. The sergeant had his squad set up the French mortar for a fire mission. Then, he took several men about a hundred meters in front of the position along the gun-target line to show them how to call for fire. The first round fell short, killing one (the sergeant) and seriously wounding several others. The explosion caught us by surprise. It was caused by a combination of errors: wrong mortar elevation; firing into the wind without compensation; and ammunition from old stocks. SSG Hapka did an emergency triage and started first aid, got IVs flowing, and stabilized them as best he could. Then, the dead man and the two most seriously injured were loaded aboard a truck. SFC Kimmich accompanied them to the province hospital in Santa Cruz. The primitive, early 1900s-vintage, medical facility did have a doctor on duty. One of the wounded died in the hospital,” remembered SSG Peterson.21

The third accident occurred during refresher tactical training provided to nine infantry companies after the Ranger Battalion mission. “We were teaching the Bolivian soldiers how to determine where a shot came from and its approximate distance away. It’s commonly called the ‘crack-thump’ method [the crack of the rifle shot provides direction while distance from the shooter to the target is determined by the amount of time elapsed before the thump of the bullet is heard]. I’m convinced that the shooter selected by the Bolivian officers did not understand exactly what he was supposed to do nor did he factor in the bullet’s trajectory when he supposedly aimed over the heads of the infantry soldiers sitting in makeshift bleachers. He was told to make it realistic and did. When the soldiers did hear the sound of the thump, half turned right and the other half, less one man, turned left. The man who didn’t turn, tumbled forward, shot in the chest. He died enroute to Santa Cruz,” remembered SFC Tom Carpenter, a light weapons sergeant on the MTT.22 These were the worst moments for the medics. The best were during the MEDCAPs (medical capability) in nearby villages and towns.

MAJ Shelton expanded his civic action efforts by supporting the requests from several Peace Corps volunteers for MEDCAP visits to their towns. In 1967, there were more than 220 volunteers serving throughout the country.23 When the visiting regional director introduced himself to the Shelton during a MEDCAP, he emphasized the “PEACE” part. The nonplussed, good humored SF major from Mississippi calmly responded, “Pleased to meet you. I’m Major Ralph Shelton from the ‘WAR’ corps. I’m glad that my medics can help out by treating these folks, seeing how most couldn’t afford to see a doctor in Santa Cruz.”24 The volunteers who lived and taught English and farming techniques in the small villages appreciated the military medics.

“We did three MEDCAPs in Las Cruces and three in Los Chacos at the invitation of the Peace Corps volunteers. We treated kids primarily. There were very few old folks. Everyone seemed to have the same skin diseases and infections that plagued the Rangers for basically the same reasons: poor personal hygiene and contaminated water. I treated one sick dog and a horse with the biggest syringe and needle that I had, a 20 cc syringe with an 18 gauge needle, to inject 20 million units of penicillin into that old nag. While we brought a field dental set, I don’t recall doing any extractions. Hugo, the barber and kiosk owner in La Esperanza, did some ‘dentistry’ on the side. He gave his ‘patients’ a few hits of aguardiente (highly potent grain alcohol distilled from sugar cane juice) and took several belts before going to work,” chuckled SSG Hapka. “We had no desire to compete with him.”25 The American medics treated more than 2,500 civilians and expended $10,000 dollars in medicine, bandages, and medical supplies.26 MAJ Shelton was so well regarded by the Indian conscripts that they asked him to help the indigenous squatters on the plantation.

A few soldiers brought the leaders of the large Indian “squatter” community to MAJ Shelton when they were about to be evicted. The New York bank holding the lien on the sugar facility wanted to sell the land to a group of Japanese and Okinawan farmers living west of Santa Cruz. “MSG Gomez and I made a trip to visit their community and meet the leaders. We invited them to La Esperanza to talk with the spokesmen for the Quechua-speaking squatters. The fat, bald-headed bank representative accompanied them. After touring the plantation and realizing what their land purchase would do to the poor folks that had built homes on the property, the Japanese and Okinawans empathized with their situation. They recalled that it hadn’t been that many years since they had come virtually penniless to Bolivia. The deal collapsed. Gomez and I became heroes in the eyes of those squatters. We both felt really good about how that turned out” said the tenant farmer’s son from Mississippi.27

Shelton also made a very conscious effort not to undermine the local economy. Beer and sodas were not to be bought in Santa Cruz and brought back to the camp. The team would patronize the establishments of La Esperanza who got their supplies via the busses from the city.28 Getting U.S. Embassy support for a new school became Shelton’s toughest challenge.

The biggest civic action project for MTT-BL 404-67X was the construction of a new school for La Esperanza. MAJ Shelton made that decision in late April before training began. Erwin Bravo, the mayor, arranged a meeting with the town leaders, Harry Singh from the Paul Hardeman Construction Company, Sanford White from USAID, Shelton, and LTC José R. Gallardo, the Ranger Battalion commander, to get support for a new, larger school. Labor was to be provided by the La Esperanza villagers and Ranger Battalion personnel with construction skills. The lion’s share of the money for the building materials would come from USAID. Bravo suggested a school fiesta to launch the effort. It was set for 25 June 1967 when the priest was available to give a blessing to the project. He wanted to get the whole community behind the effort. He thought that donations, regardless of the amount, would bolster commitment.29 Construction materials arrived in mid-July for local workers to get started on the new school.30

“Our musical group was usually me on my Gibson guitar, Fricke on the wash tub bass, Bush on the spoons, and someone on the shakers,”said MAJ Shelton.31

Progress on the new school was constantly slowed down by USAID payments. MAJ Shelton doggedly kept up pressure on the regional USAID director, Sanford White, in Santa Cruz, who dribbled the money down a tight funnel to Harry Singh, the road builder. The three month project was dragged out almost six months by the embassy bureaucrat.32 Intervention by GEN Porter in late August to get the windows and a roof on the building before the rains came actually slowed the project. To demonstrate who was in charge in Bolivia, Ambassador Douglas Henderson directed that USAID delay funds another month. “Though the bureaucratic pettiness of the State Department folks frustrated me to no end, it was seen as normal by Jorgé, who had to depend on a national ministry and province officials to fund the school and pay his salary. That man had the patience of Job,” said Shelton.33 It was mid-October when White came to visit the school project in La Esperanza. He left $800 for the roof and said that the ambassador was holding $300 in reserve. In his November report the MTT commander wrote that window sills (without windows) had been installed and the roof was almost completed.34 The six-room (an office and five classrooms) school was finished about a week before the American soldiers returned to the Canal Zone on 22 December. “Still, it was the best Christmas present we could have given those folks,” said MAJ Shelton.35

While field sanitation was critical to the training mission success, it was the practice of medicine and civic action projects that “won the hearts, minds, and loyal support of the people.” These set positive conditions that enabled the SF MTT to mold 650 peasant conscripts and their officers into a well-trained, elite Ranger Battalion capable of defeating the Cuban-led insurgent threat in Bolivia in 1967.