FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

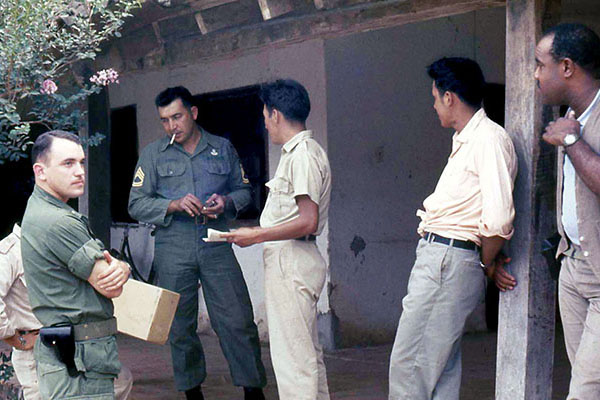

Three weeks after being alerted for the Bolivia mission, the 8th SFG MTT’s main body flew from Howard AFB, Panama on 29 April 1967 to organize, equip, and train an elite Ranger Battalion. Two C-130 Hercules cargo aircraft carried fourteen SF officers and sergeants, personal and unit equipment, training materials, and supplementary foods to support a deployment for up to 179 days, the maximum allowable time for a temporary duty (TDY) assignment. The mission was to train and prepare a special infantry element to defeat a foreign-led insurgency in remote southeast Bolivia. It was not an unusual assignment.

U.S. Army Special Forces teams had been serving as “force multipliers” training foreign troops to counter insurgency throughout the region and in Southeast Asia since the early 1960s. The SF soldiers had to learn all they could about the host country, its armed forces and police, and the guerrillas. Since these small mobile training teams (MTTs) were the “tip of spear” of U.S. national strategy, they had to have solid support to accomplish their missions.

With SF teams deployed throughout Latin America, the 8th SFG operations center (OPCEN) maintained a 24-hour communications watch. The sensitivity of the Bolivia mission required communications personnel with the highest security clearances. The 8th SAF (Special Action Force, Latin America) had 401st ASA (Army Security Agency) Detachment radio operators in the OPCEN when MTT-BL 404-67X launched.1

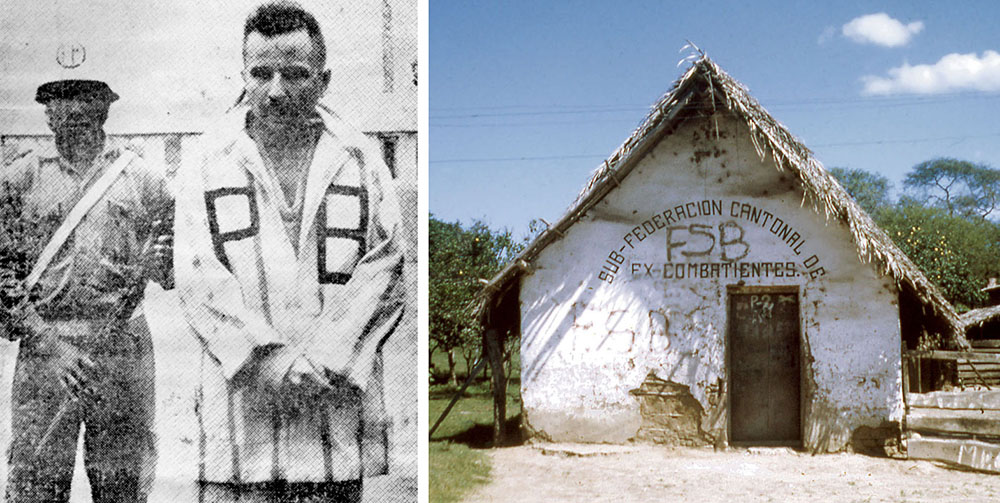

“It was a long non-stop flight, but we landed on the dirt airstrip at Santa Cruz, unloaded everything and put it aboard the waiting 8th Division [Bolivian] trucks, and headed north to La Esperanza. It took more than the usual hour and a half to drive there, but we finished unloading shortly before sunset. Talk about a long day, that was one,” said MAJ Ralph “Pappy” Shelton.2 “As we taxied to the small terminal, I spotted MSG Milliard and SFC Rivera Colon waiting for us. They were wearing their green berets; ‘So much for a low profile!’ The major dealt with this by having all of us put on our berets. Supposedly, it was important that we make a grand entrance,” said SGT Graham. “So we put on our berets. But after that, we wore them only on special occasions: when we introduced ourselves to the new battalion, when visitors came, and during ceremonies.”3 The following is a description of La Esperanza by Dorys Roca, who lived there in 1967:

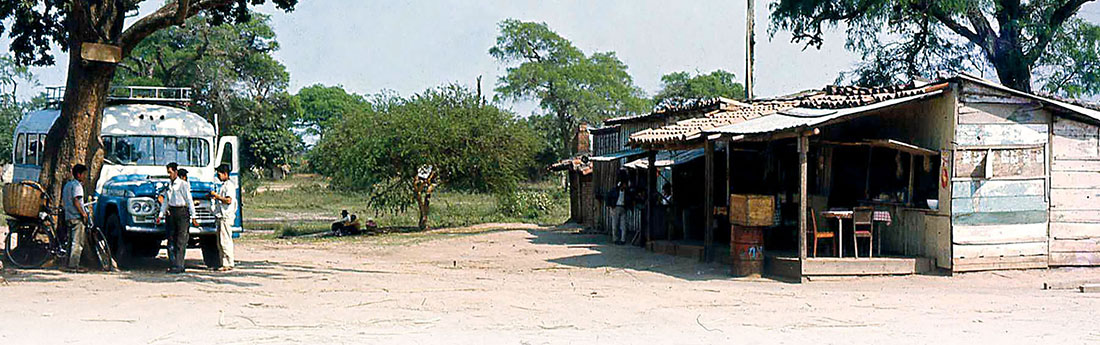

“La Esperanza had somewhere between a hundred and two hundred people living there when the Americans and the Bolivian Rangers came to town in 1967. Only a few indios [Indians] lived in the village. Most men worked out of town and came home on weekends to be with their families. There were a lot of people here in the early 1960s before the sugar mill went out of business. Still, we had no electricity and got our water from the well in the plaza where the kiosks were,” said Dorys Roca, who later married SF Sergeant Alvin Graham. “Our house had three rooms filled with beds for the fourteen of us. Because we had no heat, we slept huddled together. The cooking was done in an outside adjacent shed. Every family had an outhouse. We used a nearby lake to wash and do laundry. Once or twice a year we rode the morning or afternoon bus or hopped a truck to Santa Cruz to buy shoes and clothes. There was a church, but the priest was responsible for several villages. You would call him a ‘circuit rider,’ I guess. But, every Christmas and All Saints Day everyone walked in a procession around the town. School was year round. No one had a car or truck; one either rode a horse or walked. Children were delivered by a midwife. Compared to the States, living conditions were primitive, but daily life, though simple, was pleasant.”4