FULL SERIES: SF IN BOLIVIA

- Beggar on a Throne of Gold: A Short History of Bolivia

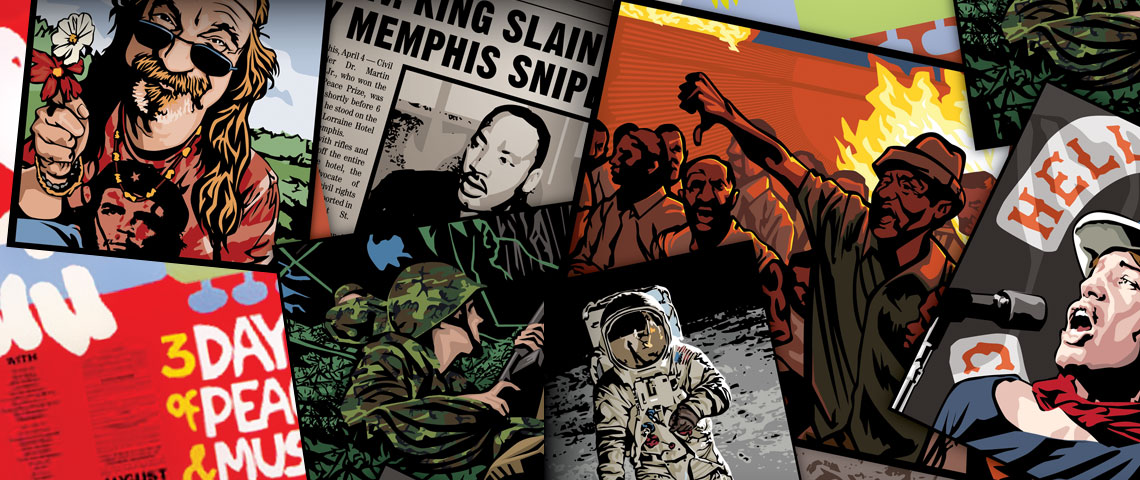

- The 1960s: A Decade of Revolution

- The Sixties in America: Social Strife and International Conflict

- Che Guevarra: A False idol for Revolutionaries

- The ‘Haves and Have Nots’: U.S. & Bolivian Order of Battle

- “Today a New Stage Begins”: Che Guevara in Bolivia

- Turning the Tables on Che: The Training at La Esperanza

- Che’s Posse: Divided, Attrited, and Trapped

- The 2nd Ranger Battalion and the Capture of Che Guevara

- The Aftermath: Che, the Late 1960s, and the Bolovian Mission

DOWNLOAD

News of the death of Ernesto “Che” Guevara on 9 October 1967 reverberated around the world, but it quickly lost relevance in the maelstrom of other world events. His demise gained more significance many years later when Che’s image became mainstream popular culture. From the perspective of U.S. Army Special Forces, his elimination as an insurgent is attributed to Mobile Training Team MTT-BL 404-67X. The Bolivian mission remains one of the few unqualified strategic COIN successes. This article will briefly explain the immediate reaction to Che’s death, the events in the late 1960s that eclipsed it, how his image was later distorted to that of a revolutionary martyr, and sum up the accomplishments of the 1967 Bolivian MTT.

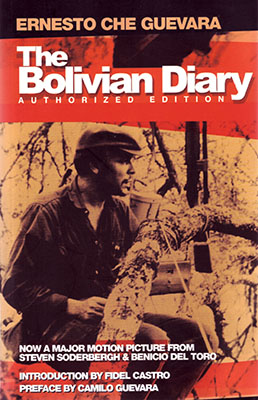

There was an immediate reaction in Bolivia to Che’s death. Many who saw his body before it disappeared, likened it to that of Jesus Christ. The media scrambled for “first rights” to Che’s diary, because it might be “the most important narrative of the last few years.”1 Their effort failed because the Minister of Internal Affairs, Antonio Arguedas, was a Cuban sympathizer. He secretly mailed a copy to Havana, where it was immediately published. The revelation that President René Barrientos had a closet Marxist in a top cabinet position threatened to topple the government. Violent demonstrations resulted, and they were the closest Che came to accomplishing his goal in Bolivia. Che’s death spurred protests in the United States as well.

On 11 October 1967, the Special Assistant for National Security Affairs, Walt W. Rostow, told President Lyndon B. Johnson that Che was dead. His memo read: “It shows the soundness of our “preventive medicine” … it was the Bolivian 2nd Ranger Battalion, trained by our Green Berets … that cornered him and got him.”2 On 21 October, a crowd of more than 50,000 war protesters gathered in Washington D.C. to show their respect for Che with a moment of silence.3 In Moscow, 200 foreign students demonstrated outside the U.S. Embassy.4 But, Che’s downfall quickly became just a “blip” on the Cold War radar screen.

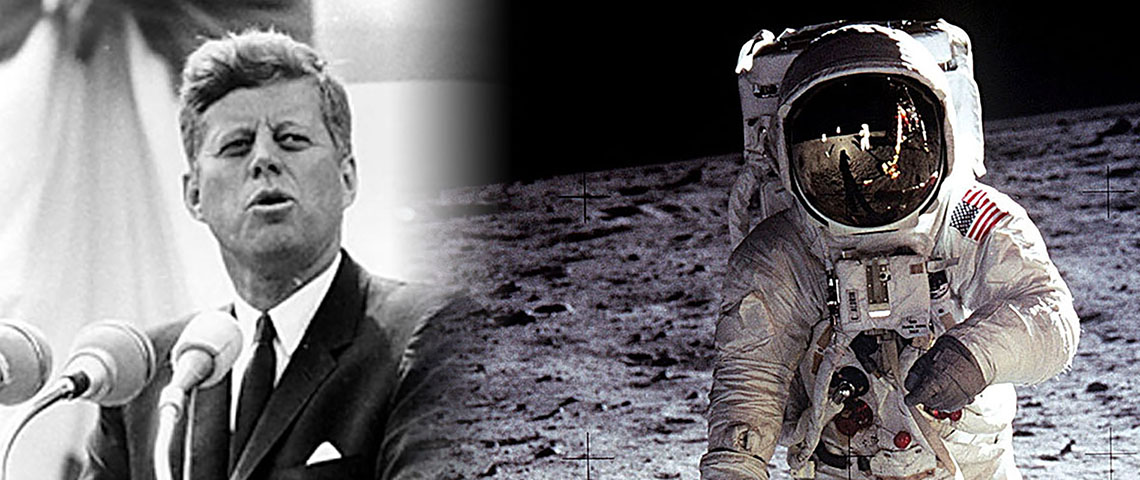

The Vietnam War had gotten America’s attention. In late 1967, the Communist North Vietnamese Army and the insurgent Viet Cong launched the Tet Offensive countrywide. Even though they were dealt a shattering defeat, the Saigon attacks proved to be a major psychological victory for the Communists. The international press corps, housed in hotels in Saigon, were suddenly in “harm’s way.” Americans, watching the war nightly on television, saw the drama unfold. Historian Don Oberdorfer wrote: “the Tet Offensive shocked a citizenry which had been led to believe that success in Vietnam was just around the corner.”5 Perhaps the most momentous event of the 1960s—a counter-response to the Soviet initiated space race—shadowed the death of Che Guevara.

On 12 September 1962, President John F. Kennedy explained why America should put a man on the moon; because it was hard, not easy.6 President Kennedy’s promise was fulfilled on 20 July 1969, as more than 600 million television watchers saw Apollo 11 astronauts Neil Armstrong and Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin walk on the moon. The triumph marked the best of man’s achievements, while domestic events showcased America’s problems.

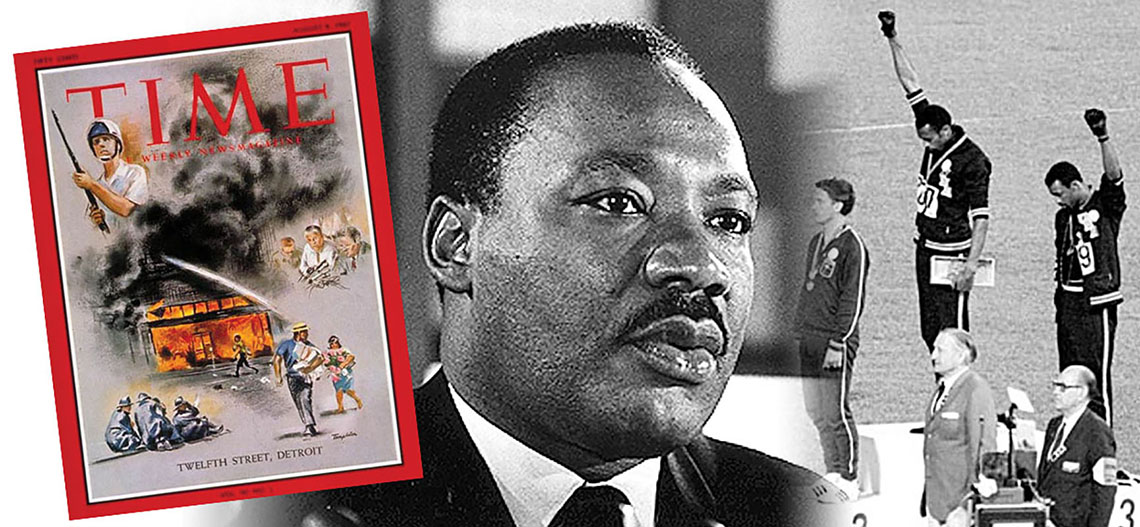

The struggle for Civil Rights had turned violent. In mid-1967, a wave of race riots spread across the northern U.S. The largest, in Detroit, began on 23 July 1967. Forty-three people were killed, hundreds injured, and over 2,500 stores were burned and/or looted. President Johnson quelled the riots with federalized National Guard and the 82nd Airborne Division. On 4 April 1968, Civil Rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tennessee. One of the first to break the news was Senator Robert F. Kennedy, who personally implored Americans not to turn to violence.7 His plea was ignored by many. The Washington D.C. riots, starting that night, were the most significant, lasting until 8 April when President Johnson again called in federal troops. Even counter-culture frivolity turned bad in 1969.

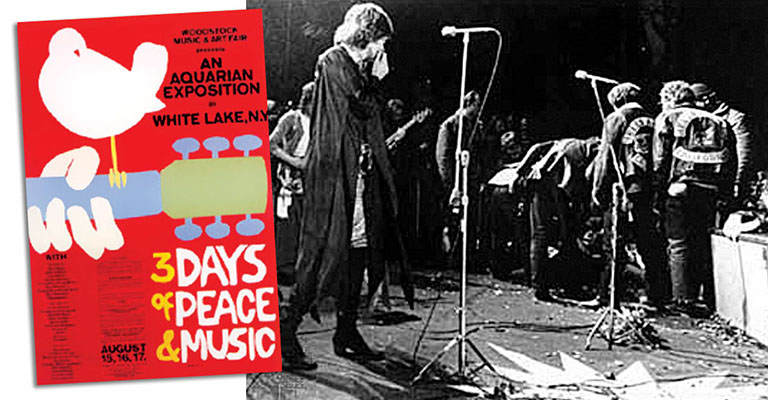

The Altamont Free Concert in northern California on 6 December 1969, was promoted as the “Woodstock West,” after the vastly popular festival four months earlier. The violence during Altamont destroyed the counter-culture image. While the Rolling Stones were performing the finale, Meredith Hunter approached the stage with a drawn revolver. Members of the Hell’s Angels Motorcycle Club, tasked to provide security, stabbed and kicked Hunter to death in front of the crowd. Unaware of what was happening, the Stones continued playing. The counter-culture drug and free-love rock festivals ended soon after. Cuba’s proclamation of Che’s martyrdom went unnoticed by the party-goers, but the Argentine became a symbol of the era.

In a secret 1967 memo, the U.S. Department of State announced that Havana would eulogize Che Guevara “as the model revolutionary who met a heroic death,” and warned that other leftist elements would follow suit.8 On 19 October 1967, Fidel Castro delivered a lengthy eulogy praising Che for his sacrifices and encouraged everyone to follow his example.9 Memorials were built to honor him. By the time Che’s body was returned to Cuba in July 1997, he had been transformed into a global symbol of revolution, resistance, anarchy. Che’s image had also been commercialized.

Alberto Korda’s 5 May 1960 photograph of Che in Havana, entitled Guerrillero Heroico, first reproduced as a print and poster, became emblazoned on clothing as a symbol of popular culture. The British Broadcasting Cooperation (BBC) called it “perhaps the most reproduced, recycled and ripped off image of the 20th Century … It began to be used as a decoration for products from tissues to underwear.”10 “Che” mania became so crazed that a lock of his hair, snipped off his head after death, and other personal effects sold at auction in October 2007 for $119,500.11 For a dedicated Communist like Che, commercialization was the ultimate insult. Most who wear his image on a T-shirt know little about him and what he represented, and capitalist entrepreneurs have had the last laugh … all the way to the bank. One question remains to be answered.

Che’s foco theory of guerrilla warfare was largely disproved in Bolivia. The U.S. Department of State determined in 1967 that those attempting to “initiate Cuban-style guerrilla warfare will be discouraged, at least for a time, by the defeat of the foremost tactician of the Cuban revolutionary strategy at the hands of one of the weakest armies in the hemisphere.”12 But others tried to adapt his foco ideas to fit insurgencies in Nicaragua, El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru, Colombia, Bolivia, Brazil, and Venezuela.13 The Cuban revolutionary model was hard to apply in the rest of Latin America.14 This was especially true when SF soldiers trained enthusiastic, dedicated, proficient infantrymen to effectively counter insurgency.

The Bolivia mission demonstrated that Special Forces are truly force multipliers. They can have a strategic impact with COIN training. When MTT-BL 404-67X left the Canal Zone to perform their mission they did not know that Che—in modern terms a High Value Target (HVT)—was in Bolivia, only that the country needed help countering a Communist guerrilla threat. They performed this sensitive mission to the highest standards. American training enabled the Bolivian Rangers to capture Che less than two weeks after finishing their course of instruction. Che was eliminated, his foco theory discredited, and Latin American militaries were shown that even the most poorly-resourced armies can defeat Communist insurgencies. This MTT-BL 404-67X forty years ago did what today’s Special Forces are trying to do in Afghanistan, Iraq, Colombia, and the Philippines: help their armed forces end insurgency.