ABSTRACT

The U.S. military was slow in exercising Civil Affairs during and after Operation JUST CAUSE. This became evident when 11,000 refugees turned the Balboa High School grounds into an impromptu Displaced Civilians facility. A pragmatic and common-sense approach by the untested 96th Civil Affairs Battalion snatched success from the mouth of disaster.

TAKEAWAYS

- The U.S. military did not plan for refugees during Operation JUST CAUSE.

- Despite having no experience in DC operations, the 96th CA contingent provided order, sanitation, food, and shelter for thousands of displaced Panamanians.

- The CA soldiers worked by, with, and through Panamanian partners who accepted ownership. Together, they established stability and improved the lives of thousands facing chaos.

- The Balboa High School DC facility was high visibility. A poorly handled effort would have invited international criticism. Problem solving and hard work by the 96th CAB soldiers resulted in a well-run Panamanian ‘owned’ facility.

DOWNLOAD

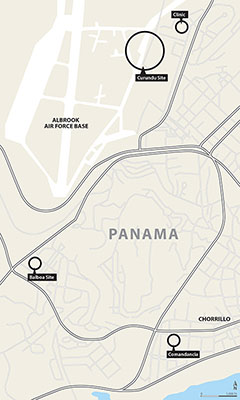

Prior to the U.S. invasion of Panama, little time was invested in post-conflict stability planning. Operation BLIND LOGIC (later changed to PROMOTE LIBERTY) contained only vague guidance for Panama’s recovery after the removal of its dictator, Manuel Noriega. Even the U.S. Southern Command (USSOUTHCOM) Commander, General (GEN) Maxwell R. Thurman, admitted that he “did not even spend five minutes on BLIND LOGIC.”1 No thought was given to displaced civilians (DC). That oversight became apparent early on 20 December 1990 when combat operations made thousands homeless. Noriega-supported paramilitary Dignity Battalion (DIGBAT) thugs set fires to divert the U.S. assault on the Comandancia, the headquarters of the Panama Defense Forces (PDF).2 Uncontrolled fires burned the surrounding ‘wood-shanty’ barrio of El Chorrillo, where 25,000 poverty-stricken dwellers lived in a few city blocks.3 With their homes in flames, the residents fled to the American-run Balboa High School a mile away. First Lieutenant (1LT) David W. Roberts, 4th Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, 5th Infantry Division, had already set up a battalion aid station there to support the attack.4

Since planners had not designated an alternate location, the Balboa High School campus became a temporary, de facto DC facility.5 Likewise, poor planning, chaos, and the increasing growing population left the facility on the cusp of a humanitarian crisis from 20 December to 22 December 1989. That situation changed when the 96th Civil Affairs Battalion (CAB) was given the mission. Relatively untested CA soldiers pulled the Joint Task Force (JTF)-South effort ‘out of the fire.’ This ‘case study’ examines Company D, 96th CAB management of the Balboa High School DC facility from 22 December 1989 to 12 January 1990. It explains the level of Civil Affairs readiness for combat in Panama and the rationale for the refugee facility, as well as what the CA soldiers encountered and how they solved the immediate problems. The major events flow in sequence, but many problems were dealt with simultaneously. Before discussing this impromptu mission, it is necessary to explain the state of CA then.

In 1989, CA was not a Regular Army Branch; it was a functional area. Ninety-six percent of Army CA was in the Reserves. The 96th CAB was the only active-duty CA battalion.6 While the battalion was assigned to the U.S. Army 1st Special Operations Command (1st SOCOM), CA was an ‘outsider’ until designated a Special Operations function by the U.S. Special Operations Command (USSOCOM) in 1993. Prior to JUST CAUSE, 96th CA teams assessed civilian institutions and infrastructure for Special Forces Groups. The 96th CAB aligned its four companies regionally. Each company had five, four-man teams.7 Its strength of 125 soldiers limited missions to short term tactical missions.8

Army leadership was focused on combat units. Few knew how to employ CA or grasped its capabilities. The CA reputation in and employment by Army Special Operations Forces (ARSOF) likewise suffered from a lack of understanding.9 This negative perception of CA meant that assignment to the 96th CAB was not career-enhancing. The only active CA battalion had no ‘champion.’ It did not help that the vast majority of soldiers assigned were not graduates of the six-week CA course. This included the battalion commander.10 With the exception of Company A, which had some native Spanish speakers, few soldiers spoke a second language fluently.11 However, the 96th soldiers came from different backgrounds. They had been to Basic Combat Training, Advanced Individual Training, and Non Commissioned Officer (NCO) schools, and the officers were basic-branch qualified. This background saved them in Panama.

JUST CAUSE operational planning (code-named BLUE SPOON) force-listed Company A, 96th CAB to assist the 75th Ranger Regiment with the capture of the Torrijos-Tocumen Airport Complex and the Rio Hato airfield. After the JUST CAUSE assaults, a small CA command element was to deploy to determine future requirements.12 That ‘floating’ plan became obsolete early on 20 December when GEN Thurman complained to GEN Colin L. Powell that he had no CA units.13 The Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the 96th CAB (-) to deploy to Panama. It arrived on the 22nd.

The 96th CAB commander, Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Michael P. Peters, went to the J-5 (Civil Affairs) of JTF-South for guidance. LTC A. Dwayne Aaron directed Peters to provide CA teams to tactical units throughout Panama, conduct Humanitarian Assistance, help American citizens return to the U.S. if they wished, and assist at the Balboa High School DC facility.14 The latter proved to be the most complicated mission.15

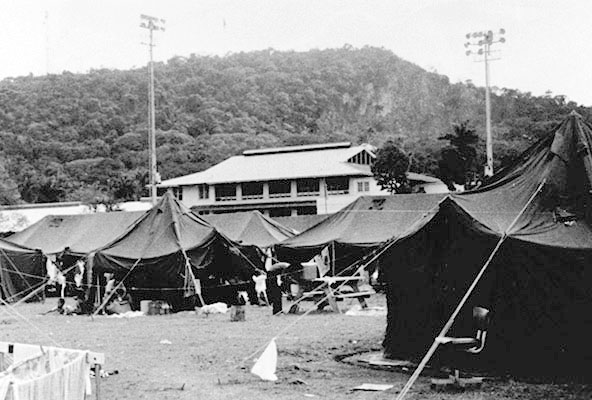

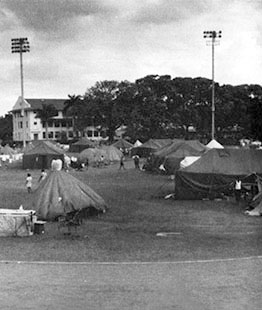

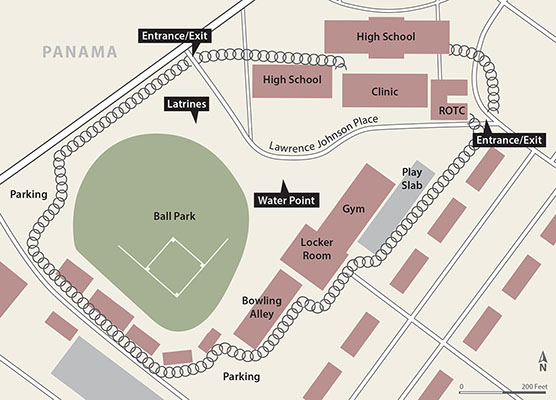

Thousands of DCs had squatted on the high school grounds before U.S. forces could respond. The refugees broke into the gym, seeking cover and access to bathrooms. Others erected makeshift shelters on the baseball field. Surprisingly, they did not break into the school. The chaos accompanying a mass of poor, hungry people facing an absence of sanitation, shelter, and security, was a huge humanitarian crisis that required immediate attention. A poorly-run operation would increase the wartime hardships for Panamanians. This threatened to negate U.S. efforts to limit its war with Noriega, not the people. The presence of major news correspondents at the high school meant that failure would be publicized and politically embarrassing.

LTC Peters gave the Balboa High School mission to Company D, whose commander, Major (MAJ) Michael A. Lewis, was a Military Police (MP) officer. MAJ Lewis was to establish order. LTC Peters stated that that MAJ Lewis was “the most obvious choice. He had the right demeanor, was even tempered, and not easily flappable.”16 Together they went to the DC facility to meet the officer in charge, COL William J. Connolly, the United States Army South (USARSO) Deputy Chief of Staff, Resource Management (DCSRM). On 19 December 1989, the acting USARSO Chief of Staff had sent COL Connolly to USSOUTHCOM to “help fix” the neglected BLIND LOGIC operation order.17 With just a day to do this, COL Connolly focused “on the refugee issue, assuming that it would be one of the first problems with which the military would have to cope as the result of combat operations.”18 He was right. When the DCs squatted at the Balboa High School, COL Connolly was the most experienced available officer. COL Connolly and his four subordinates faced a tremendously difficult mission. The reality was evident during a quick ‘walk around’ with LTC Peters and MAJ Lewis.

COL Connolly explained his dilemma. Combat units working in Balboa provided security. He could request engineer support from USARSO, but the priority of combat operations limited availability. As LTC Peters surmised, COL Connolly had to “count on the help of other units [over] which he had no control.”19 There was one exception. COL Connolly had gotten a Preventative Medical Section from the Gorgas Hospital to support an infantry battalion medical aid station that had been set up next to the school.20

Because it was closed for Christmas break, the high school principal had been willing to open the building as needed. COL Connolly put the military administration in a classroom. LTC Peters and MAJ Lewis saw that hallways and a few other classrooms had been transformed into infirmaries, urgent care facilities, and medical supply rooms. The elderly and pregnant women were in separate classrooms. To prevent the spread of illness, COL Connolly had isolated sick children with their mothers.21 That was the upside. The rest of the DC facility was in chaos.

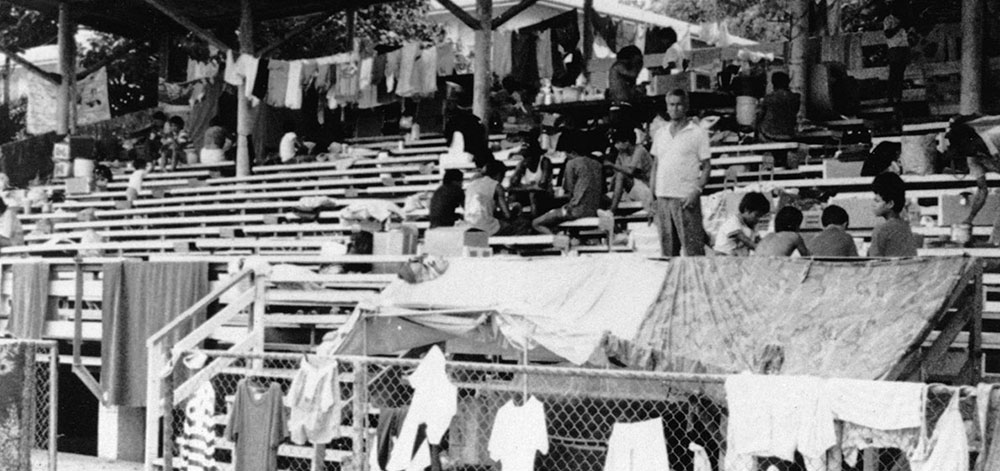

Thousands of DCs were squatting on the high school grounds and hundreds more were arriving daily. Refugees were coming and going at will, making it impossible to get an accurate headcount. Some were merely transients who lived with family members outside the facility. They returned for food, or to use the facilities. Others had nowhere to go and stayed. In the gym, women and children slept in cramped quarters on the floor. LTC Peters and MAJ Lewis saw that the toilets were backed up. The stench was awful. Makeshift ‘tents’ filled the baseball field. People were sleeping in the bleachers. The torrential afternoon rains of the tropics and the masses of people had turned the grass into “a sea of mud,” said LTC Peters.22

The ‘walk-through’ showed LTC Peters the magnitude of the problem. With multiple commitments, LTC Peters could only give MAJ Lewis nine personnel. However, the 96th Tactical Operations Center (TOC) on nearby Fort Clayton would help. COL Connolly was redirected on 27 December to fund the ‘money for weapons’ program. This left MAJ Lewis and his second-in-command, CPT Gregory J. Rhine, to turn the DC mess into a sanitary humanitarian refuge.23 MAJ Lewis divided his team to cover operations, sanitation, and logistics.