NOTE

*Pseudonyms have been used for all military personnel with a rank lower than lieutenant colonel.

DOWNLOAD

Psychological Operations is an essential part of any counter insurgency campaign. Over the past two decades, United States Army Psychological Operations (PSYOP) has covered the full spectrum of support, from leaflets and posters to radio and television broadcasts to sophisticated websites, all designed at influencing the population of a target country. In Colombia PSYOP changed over the past ten years from focusing exclusively on counter drug programs to counter narco-terrorism (CNT) after the 9/11 terrorist attacks (and ”expanded authority” granted by the United States). This article discusses U.S. Army PSYOP in support of the war in Colombia as it evolved from the Overt Peacetime Psychological Operations Program (OP3) to counter drug operations in Plan Colombia to the counter-narco-terrorism mission under the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT).

For many years U.S. Army PSYOP has provided support to the U.S. Embassy in Bogotá, Colombia through the auspices of the Overt Peacetime Psychological Operations Program (OP3). Begun in 1984 by the Department of Defense, OP3 is developed and controlled by geographic combatant commands, in coordination with the U.S. Ambassadors in various countries.2 In U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM), the OP3 assists U.S. allies throughout South America.3 With the rise of illegal drug trafficking from South America to the United States, the majority of OP3 in SOUTHCOM has concerned counter drug (CD) programs, with Colombia becoming the focus of support. In the case of Colombia, SOUTHCOM and the U.S. Embassy plan and support psychological operations through OP3. Under OP3, PSYOP may be conducted in support of U.S. regional objectives, policies, interests, theater military missions, or during military operations other than war, including counter drug operations.4 Colombians also received training at the School of the Americas (at Fort Gulick, the Panama Canal Zone, and then at Fort Benning, Georgia), but also at the U.S. Army John F. Kennedy Special Warfare Center and School at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. U.S. Army PSYOP support was also offered to Colombia. Mobile Training Teams from the 1st POB went on temporary duty tours to Colombia, but their support was not continuous until 1990.

In May 1990 a three-person team traveled to Bogotá to discuss a possible PSYOP mission with Colombian and U.S. officials. The meeting proved to be productive and set the stage for a series of long-term deployments. By July, a second U.S. PSYOP team visited two Colombian Army divisions to assess their PSYOP capabilities and programs. Based on their assessment, a PSYOP team spent two weeks that November conducting target analysis and product development workshops at the Colombian 2nd Division (in Bucaramanga) for battalion and brigade PSYOP officers. The workshops included a practical assignment that allowed the Colombians to develop products targeted to their individual regions of assignment. In order to have continuity and to provide support, a move was then made to temporarily place PSYOP soldiers in Colombia on a continuous basis.5

Since U.S. PSYOP support was limited to counter-drug operations, it limited the amount and type of PSYOP support that could be provided to the Colombian military and its operations. Because of the limitations, by 1991 the majority of U.S. PSYOP support went to the Colombian National Police (CNP) whose primary role was counter drug. The CNP had established the Centro de Operaciónes Sicológicas (COPSI—Psychological Operations Center) that dealt with counter drug operations. Just as the U.S. PSYOP effort in Colombia gained momentum, however it was stymied when the majority of the assigned personnel were temporarily pulled for duty with Operation SAFE HAVEN (the Haitian refugee crisis at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba), but support would begin again in earnest in the next year.6

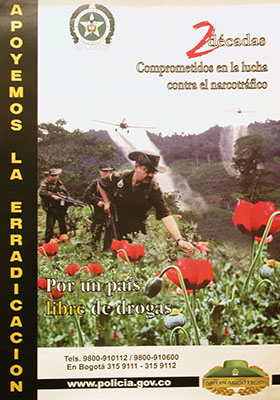

By 1992, the main component for U.S. PSYOP in Colombia was the Military Information Support Team (MIST). Based out of the U.S. embassy, the MIST worked with the Colombian police, military, and government agencies to advise and assist in counter drug (CD) products and programs.7 These counter drug programs centered on four basic tenets: Interdiction; Eradication; Human Rights; and Alternate Economic Development. The composition of the MIST was austere and generally consisted of only four personnel (the commander, a 37A PSYOP Officer, either a captain or major; a NCOIC, a 37F E-7 or E-6; PSYOP sergeant, 37F E-5, and a 25M Illustrator). The MIST-Colombia soldiers would rotate every 179 days. However, due to administrative and training requirements the soldiers usually spent between 90 to 120 days in country.8

U.S. PSYOP was limited to counter drug support, with the single exception of the Infrastructure Security Strategy (ISS) in a very narrow area in the Arauca department. As the Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) increased attacks on the oil pipeline, in 1997, Occidental Petroleum lobbied Congress for help. Under the ISS mission, a 7th SFG reinforced Company trained the Colombian 18th Brigade to protect the pipeline. Integrated into the training was a PSYOP campaign. The 1st POB sent a team with the 7th SFG to train and advise newly formed Colombian tactical PSYOP teams at the Colombian PSYOP school. After an area assessment, the PSYOP team leader found that each unit in the Arauca department operated a small FM radio station. Counter insurgency radio programs were then developed and broadcast. For the duration of the ISS mission U.S. PSYOP could actively be involved in supporting the Colombian counter insurgency campaign.9

The 9/11 terrorists attacks on the United States expanded the scope of U.S. involvement in Colombia from a strictly counter drug mission to a combined strategy of counter narco-terrorism (CNT). The shift caused by the “expanded authority” increased U.S. military involvement in the war on narcotics traffickers and terrorists. Prior to the policy shift, U.S. PSYOP support for Colombia could not target, or assist in the targeting, of guerrilla organizations, even though they were providing security for the drug producers and traffickers. Under the auspices of National Security Presidential Directive 18 (November 2002), the U.S. military was allowed greater coordination authority with the Colombian military, including sharing intelligence and PSYOP support.10 Under this “expanded authority,” PSYOP could now assist not only the Colombian National Police, but also the Army, in the fight against the narco-terrorists.11

With the “expanded authority” policy shift, the MIST changed its name to “PSYOP Support Element (PSE).” In January 2003, with the increased mission, the newly renamed PSE—Colombia grew to 12 soldiers. To avoid confusion within the Embassy, and the Colombian military, most continued to refer to the PSE as a MIST. In November 2006, U.S. Special Operations Command changed its policy, and now all PSEs are officially referred to as MISTs.12

Unique to Colombia was an abbreviated product approval process. In the early stages of Operations ENDURING FREEDOM and IRAQI FREEDOM the approval process went up the chain of command to the combatant commander and in some cases to the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The PSYOP product approval process was streamlined in Colombia. PSYOP products developed by the PSE-Colombia soldiers were reviewed by the Military Group (MILGP) Commander, then staffed through the embassy public affairs officer, and approved for dissemination by the Deputy Chief of Mission (DCM).13 Since the major cities of Colombia, especially Bogotá, have a highly developed printing industry, products are produced in Colombia rather than the U.S.14

The assignment to Colombia is an example of flexibility for the PSYOP soldiers. The majority of time is spent dressed in a civilian suit working on strategic and operational issues at the embassy or the Colombian military headquarters (the equivalent of the Pentagon). In the very same week, the soldiers may be in the field teaching techniques to the Colombian PSYOP soldiers.15

Since the 1990s the Colombian Army has developed its own tactical PSYOP capabilities. The U.S. PSYOP soldiers assisted in training the Colombian Groupo Especial de Operaciónes Sicológicas (GEOS—Psychological Operations Special Group). The GEOS units are assigned to each of the Colombian Army Divisions, to provide organic PSYOP support. Through the auspices of the U.S. Embassy’s Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS), the Colombians received specialized PSYOP equipment and training. Each division headquarters is equipped with a tactical development center with a computer workstation and a print risograph machine. For tactical operations, the GEOS detachments are equipped with still and video digital cameras and LSS-40B Tactical loudspeakers; the same type used by U.S. soldiers.16

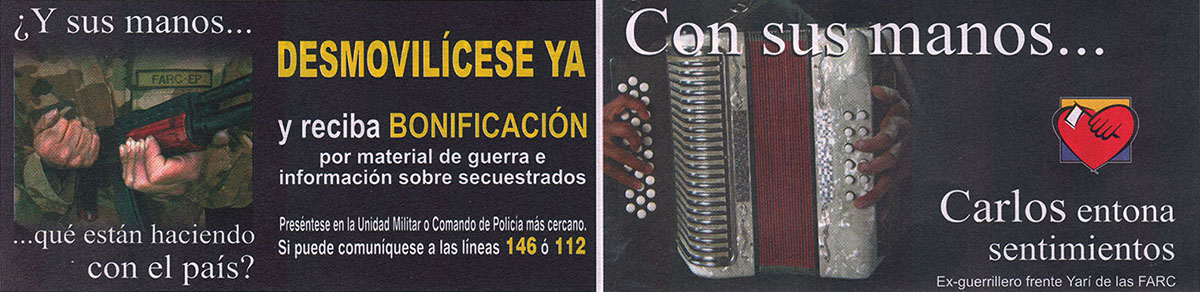

One of the major programs run by the PSYOP section at NAS is the Humanitarian Demobilization, a major effort under the Uribe administration to encourage insurgents to reintegrate back into the society. Planning for NAS PSYOP is the responsibility of a small staff section with an Army PSYOP officer assigned to NAS on a three-year tour. In the summer of 2006 the PSYOP Officer, Major Tomas Suarez*, had over ten years of experience in Latin America, most in Colombia. The Humanitarian Demobilization program encourages insurgents, both right and left, to put down their arms and reintegrate into society. The program is a highly sophisticated multi-media campaign using radio, television, newspapers, posters, and leaflets. If the former guerrilla has no record of human-rights abuses amnesty is given. In addition to the amnesty, the former guerrillas are eligible to receive retraining for a trade, a small business loan, and a cash “bonus” for laying down their arms. By the end of 2006, on the average every three hours, a guerrilla turned himself in to either the police or army; 56 percent come from the FARC.17

The key to good PSYOP in Colombia, as anywhere else, is a detailed target audience analysis (TAA), the accuracy of which can “make or break” a product or even an entire campaign. In the 4th PSYOP Group, the TAA process is assisted by the Strategic Studies Detachment (SSD) assigned to each regional PSYOP battalion. One of the early tasks for U.S. PSYOP personnel was to assist the Colombians in human rights training. The question was posed “how do you produce a human rights product that soldiers will look at and keep?” The solution was to produce a wallet-sized card with the picture of one of Colombia’s top bikini models on one side. The target audience of primarily young male soldiers not only kept the card, but it also became a coveted collector’s item. Innovative concepts such as this resulted in one of the most successful human rights campaigns ever seen in Colombia and a drastic increase in the Colombian military’s commitment to the protection of its citizen’s basic human rights.18

Historical examples can sometimes work in other environments, but there first must be a detailed target audience analysis. One example is the deck of cards that was used as a PSYOP product from Iraq, with Saddam Hussein as the ace of spades. The SSD and PSYOP team members advised against using this example in Colombia to identify the “most wanted” members of the FARC and ELN. Several factors lead to the assessment. First, Colombians generally do not use the same playing cards as we do in the U.S. and secondly, the American involvement in Iraq is especially unpopular in the Colombian media. A clearly U.S.-sponsored product would have undoubtedly brought unneeded negative media attention. Instead, after a detailed analysis the PSYOPers used chess, a popular game in the country, as the alternative. Both television and print media ads were developed showing a game of chess and then showing the pictures of captured FARC members. The television ad was shown as a public service message, during the most viewed “novelas,” the extremely popular nighttime soap operas. As new FARC leadership surrendered, were captured, or killed, the Colombians updated the ad showing the individuals.20

Something that is relatively small can have a tremendous impact on the population. In conducting a TAA in Colombia the importance of school notebooks for children (and families) was noted. School children are required to have a notebook per subject, with generally six subjects per term. The small 3”x9” notebooks cost about 2,000 pesos each (about $0.80-$0.90 U.S.), or about five to six dollars, per child per school term. In rural or urban poor areas, this could amount to about 10 percent of a family’s monthly income, just for notebooks, for one child. But, without the notebooks the child could not attend school. The solution was to provide them for free as a PSYOP product. The PSYOP-produced notebooks have a message, usually counter drug, on the front and back covers.21

Over the past two decades, as American policy changed, U.S. Army PSYOP was there to support the objectives. Beginning with a small initial assessment team, evolving to the MIST, progressing to the beginning of Plan Colombia (and its support to training and the establishment of the counter drug brigade and its three battalions), PSYOP has been an integral part of the U.S. foreign internal defense effort. Through the efforts of the soldiers and civilians of the 1st POB, U.S. Army PSYOP will continue to assist Colombia.